Walls, floors and rocks: England and its swastikas

- Published

England: a green and pleasant land... and home to a large number of swastikas, ancient and modern

Swastika. The word is a potent one. For more than one billion Hindus it means "wellbeing" and good fortune. For others, the cross with arms bent at right angles will forever symbolise Nazism. Yet England is seemingly awash with swastikas. Why?

It comes from the Sanskrit "svastika" and means "good to be", yet the word swastika - and perhaps even more the symbol which represents it - is very often taken to mean something very different.

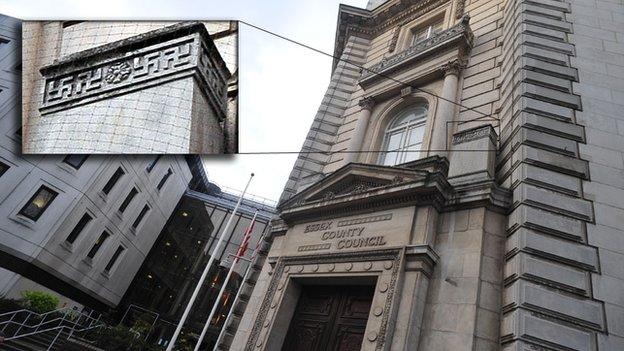

So much so, in fact, that when a member of the public recently asked Essex County Council why it allowed swastika motifs to be carved into its HQ building during the 1930s, some demanded the symbols be removed.

The case is a perfect demonstration of the seismic shift in the swastika's reputation in the West as a result of its use by Nazi Germany.

Why did Adolf Hitler and the Nazis seize the swastika?

The Nazi party formally adopted the swastika - which it called the Hakenkreuz (hooked cross) - in 1920.

Dr Malcolm Quinn, of the University of Arts London, says the party picked up on the symbol's association with the Aryans, who some intellectuals of the time believed had invaded India in the distant past.

They considered the early Aryans of India to be the prototypical white invaders and the cultural ancestors of the German people.

Initially completed in the 17th Century, Burlington House features swastika shapes in its exterior stonework

"What Hitler did," says Dr Quinn, "was to add the swastika symbol (of a conquering 'race') to the colours of Bismarck's flag and Germany was rebranded as a nation whose central mission was conquest and colonisation.

"The Nazis created a new history for themselves. Within decades the swastika had been ripped from its Indian roots."

But the swastika - or at least the shape to which the word refers - predates Hitler by thousands of years.

Dr Jessica Frazier, of the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, told the BBC swastikas had been found in China, Japan, Mongolia, the ancient Mediterranean, among native Americans and, of course, the British Isles.

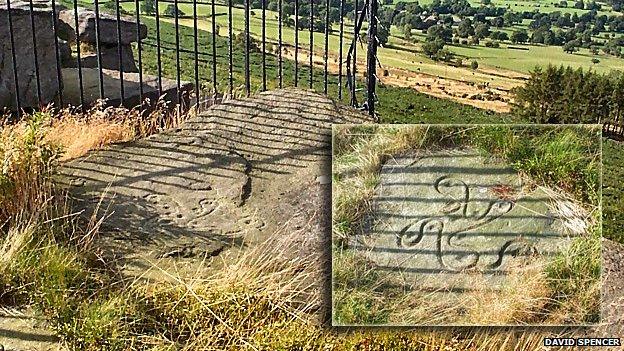

The Swastika Stone sits at Woodhouse Crag above Ilkley and overlooking Wharfe Valley

"Its (the swastika's) original meaning is an enigma," she said. "Perhaps it is just an elegant geometry which has an instinctive appeal across the world."

The earliest swastikas might have had some religious or astronomical meaning. Then again, they might not.

One of those earliest "swastikas" is the Swastika Stone which sits proudly on the edge of Ilkley Moor in West Yorkshire.

The carving is thought to be early Bronze Age dating back to about 2,000 BC.

This swastika-inspired design appears on the The Foreign and Commonwealth Office in London

Now heavily eroded from the surface of the grit stone outcrop on which it sits, the design, external features a grooved swastika with a number of circular hollows.

The name Swastika Stone, as the Yorkshire-based archaeologist Dave Weldrake explains, is a Victorian invention. And a successful invention at that.

It pulls in the tourists not because it is the most elaborate carving on the moor but because of its name.

Mr Weldrake said it was most likely a religious carving.

This section of Essex County Council's headquarters was finished in 1939, the year Britain and Nazi Germany went to war. But the designs had been finalised years before

"But there's no written record," he said. "It is one of many carved rocks in the area which vary from the really simple to the highly elaborate.

"There is another one which looks partially on the way to being a swastika and there are others with ladder patterns. Part of the problem with interpretation is you don't know how they looked at the time."

Jump forward a few thousand years and the swastika motif reappears in England in thriving abundance.

Not on rocky outcrops now, but on buildings.

One of the plaques on the outside of India House in central London bears two swastikas

Many of these motifs, says Dr Quinn, arrived in England as a result of Britain's colonisation of India during the 18th Century.

The British author Rudyard Kipling, who was strongly influenced by Indian culture, had a swastika on the dust jackets of all his books until the rise of Nazism.

Other swastika-based designs, including the Essex County Council building swastikas mentioned above, were most likely inspired by Greek patterns.

The Tympanum of St Andrew's Church, near Great Durnford in Wiltshire, features a design that resembles the swastika

Whatever their derivation, without knowing the intention of the architects who included such designs on churches, government buildings, banks and railway stations, referring to them as swastikas is problematic.

By and large, says Dr Quinn, they are "decorative motifs that happen to use the same symmetry group as the swastika symbol".

And they mostly predate Nazi Germany.

Shaunaka Rishi Das, director of the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, says: "Most Western people when they see it (the swastika), they see Nazi Germany.

"But you have to understand that here's a tradition that is ancient and the Germans borrow it from a different culture and misuse it over less than two decades and it develops an internationally bad reputation."

Mr Rishi Das told how he himself once lived in a house in Belfast which had a tiled swastika on a wash-room floor.

"It somehow survived the fact that American officers were billeted there during the war," he said. "The daughter of the man who built the house, a well known architect of his time, told me the symbol was a Celtic one."

That house, he said, later became a Krishna Temple.

Although single swastika motifs - such as one found on cottages pictured below in Aylsham, Norfolk - are not rare, it is far more common to find swastikas used in repeating patterns.

A curving swastika design was used on these pebble flint cottages near Aylsham in Norfolk

Examples include those on the The Royal Academy of Arts building at Burlington House and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in King Charles Street, London.

As Mr Rishi Das found in Belfast, walls are far from the only surfaces to carry the swastika. Floors carry them too.

The Natwest branch in Bolton's Derby Street, external, for example, has two swastikas on its floors.

When asked to remove them in 2006, the bank pointed out that the building was built in 1927 when the swastika was commonly used in architecture.

The request to remove them was turned down.

Not just for walls: a large swastika-style design on the floor of Upminster Bridge tube station in Hornchurch

The floor of The Painted Hall of the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich also features a swastika design.

And then there is this red, white and black swastika design outside the barriers to the District Line service at the Upminster Bridge tube station in Hornchurch, east London.

Could the swastika motif ever stage a comeback in western architectural design?

Dr Quinn said he was not aware of any building other than temples created since World War Two in England featuring swastikas.

And while the swastika design may well be used in Hindu architecture, its future use on public buildings seems unlikely.

- Published27 February 2014

- Published25 February 2014