Mary Ann Cotton: Campaign to keep letters in North East

- Published

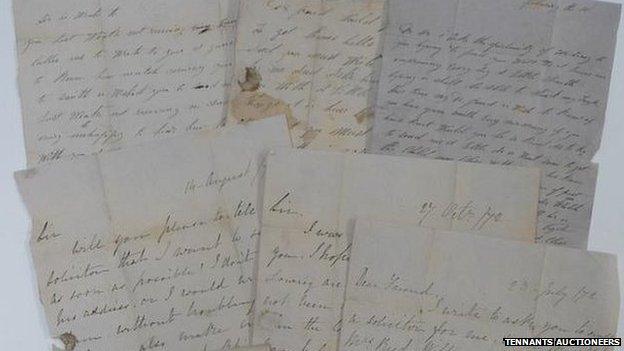

The letters were written by Mary Ann Cotton from her prison cell

A campaign to keep the letters of a Victorian serial killer to be preserved for the nation is under way.

Mary Ann Cotton was hanged in Durham Prison in 1873 after being found guilty of poisoning her stepson with arsenic.

Cotton, from West Auckland, County Durham, is also widely believed to be responsible for the deaths of up to 20, including her husbands and children.

Eight of her letters were sold in 2013 and now campaigners want to raise £4,000 to keep them in the North East.

The correspondence written from prison and addressed to a man who had lodged at Cotton's home, make reference to solicitors and financial problems.

Mary Ann Cotton was hanged in 1873

Victoria House, from Oxford, but originally from the North East, has been campaigning for them to be kept in the public domain at Durham County Records Office.

But there are now fears the letters will be sold off individually.

A Facebook page about the letters attracted the interest of Christine Cunningham, from Peterborough, who has now set up a donations page with a £4,000 target.

However, while the letters might give an insight into the mind of a killer, some now believe that she might not have been guilty in the first place.

She was convicted of only one murder, that of her stepson, after suspicions were aroused when he died shortly after she failed to get him admitted to a workhouse.

He suffered gastro intestinal problems, as had many other people the dressmaker and nurse had dealings with over a 20 year period, including three of her husbands and a number of her children and stepchildren.

Even though in all cases she claimed an insurance pay out, none of these deaths were deemed suspicious, until her stepson died.

The letters were sold by descendents of Mr Lowry, to whom they are addressed

An inquest revealed the presence of arsenic, and subsequent exhumations also found the same poison in some of the bodies.

Despite protesting her innocence, she was hanged in March 1873, the execution being delayed until after the birth of her 11th child.

However, some believe the deaths could equally have been due to poverty and poor medical facilities, and she was merely a victim of the times.

Local author, Ian Smyth Herdman, studied the court transcripts, information from the National Archives and newspapers and found a list of errors in evidence and legal process at her trial.

"The available evidence was lacking to say the least," he said.

"She had no forensic expert to rebuke the prosecutions comments, witness statements in her defence were lodged, but were not acceptable.

"In the accordance with law it would in my opinion be questionable as to her guilty verdict."

But whether she was mass murderer or misunderstood matriarch, Victoria House said: "Time is of the essence if the original letters are to be preserved together as they should be for the nation."

- Published27 February 2013