When did the length of time prisoners serve in jail change?

- Published

Prisoners in England have been eligible for early release since 1948

The debate around how long an offender should spend in jail and out on licence has been going for centuries. But when - and why - did the length of time prisoners serve in jail actually change?

It is South Carolina in the 1990s. A parole applicant appears before the board. He shuffles into the room in leg irons with red and green lights ahead of him.

Before he can open his mouth the board members hit switches igniting the red lights. For the time being, he is to remain behind bars.

In the United States there are thousands of people serving life-without-parole sentences. Yet early release on parole has been a feature of the English penal system for many years.

In 1948 it was decided prisoners should be released once they had served two thirds of their sentence. At this time there was no parole and they were released without being on licence.

Then in 1967 the Criminal Justice Act, external introduced the Parole Board and prisoners had the possibility of parole between a third and two-thirds into their sentence.

The board was the creation of two pressures coming together - a wish to find ways of reducing prison populations and a genuine belief in rehabilitation.

"Those things in the 1960s were really important and in tune with the thinking of the time - that you could change the behaviour of an offender if you adopted the right approach," Stephen Shute, professor of criminal law and criminal justice at the University of Sussex, said.

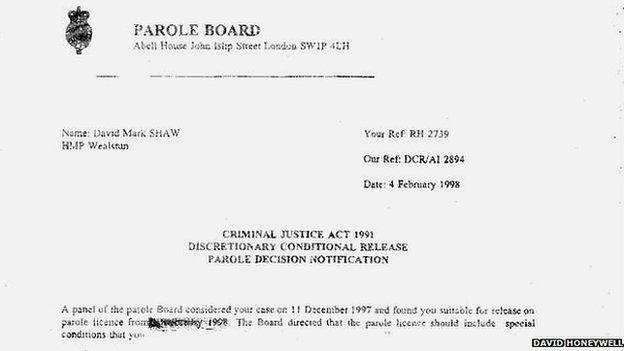

David Honeywell was granted parole twice - once in the 1980s and once in the 1990s

In 1984, then 20-year-old David Shaw - now David Honeywell - was getting his first taste of the parole system. He had served 10 months of a 30 month prison sentence for attempted robbery.

"There were a lot of people not being given parole at this time," he said.

"I was a first time offender, so that was in my favour, but a lot of guys who I was with weren't and a lot didn't get parole."

But within six months he was recalled after making a threatening comment to his probation officer and served the rest of his sentence back in prison.

While there was a general view that supervision after leaving prison was a good idea, it seemed there were a number of problems with the system.

This led to the Carlisle Committee being set up, which would go on to underpin the 1991 Criminal Justice Act.

There was a recognition that not many people were actually getting out at the one third point, and they were tending to be realised half way through their sentence, or afterwards.

"It was thought, wouldn't it be better to have a system which recognises the reality of the situation and doesn't raise the hopes of prisoners and their families unnecessarily," Prof Shute said.

"The solution seemed to be to remove all the short term cases from the parole system and focus attention on the cases that matter, where there is likely to be a higher risk to the public."

The 1991 Criminal Justice Act, external provided that any person serving a sentence of four years or more, would serve half of their period in custody - where previously it had been a third - and would then become eligible to apply for early release.

David Honeywell - previously David Shaw - was granted parole for a second time with the parole board commenting on his educational achievements and willingness to address his offending

By 1998, Mr Honeywell was back inside, sentenced to five years after committing wounding with intent. This time he served half of his sentence in jail before being released on parole.

He was subject to stricter provisions on his parole licence and told he must address his "offending behaviour".

But he struggled with life outside and committed several offences - including assault. He said he had become "reacquainted with the Newcastle underworld", but this time he was not recalled.

"They [probation] were more optimistic and felt like they could work with me and it paid off," he said.

"I was in for longer that time and I got an education."

Mr Honeywell now guest lectures about his experiences and teaches at the University of York, but thinks his rehabilitation could have been speeded up had he been kept in jail for longer in the 1980s.

"I was doing education then, but that got interrupted by the parole and as soon as I came out I was getting drunk, I wasn't going anywhere, so I would have been better off being kept in," he said.

"I wouldn't say that would suit everybody, but for me, I needed to be kept in longer."

Some prisoners say living life on parole is harder than serving time in prison, with little money or support

Throughout the 1990s the debate about not keeping prisoners in jail unnecessarily versus a threat to the public continued.

Another strand of thinking was that parole undermined 'honesty in sentencing', where a custodial term was announced in court that did not reflect the period of time the offender would actually serve in jail.

But it was argued that if you took that idea to its extreme - that there should be no parole - then you are left with the problem of people whose risk is unpredictable, and when it is safe to release them.

And so in 2005 the provisions of the 2003 Criminal Justice Act, external were introduced.

It said that any prisoners serving a determinate sentence would serve half of their sentence in custody, be released at the halfway point and remain on licence for the other half of the sentence.

For those serving an indeterminate prison sentence, the court would set a minimum term of imprisonment before the offender can become eligible to be considered for parole.

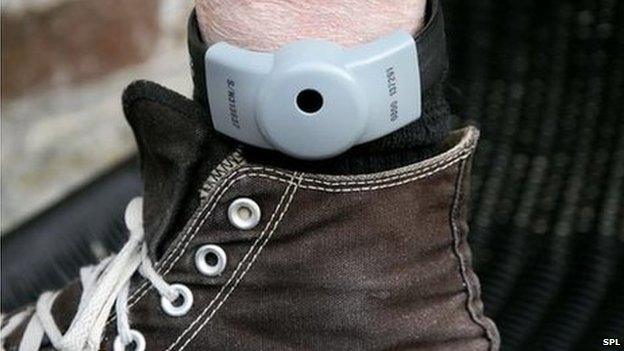

When released on parole offenders are subject to numerous conditions

The Ministry of Justice said changes made to the system have seen sentences get longer and Nicola Padfield, reader in Criminal and Penal Justice at Cambridge University, argues half a sentence on parole is "not a soft touch".

"It's not just come out and it is all over, some prisoners think it is tougher to serve their sentence in the community, on license, than it is in prison," she said.

"Prisoners may be recalled either because of allegations of further offending, which may later be withdrawn, or for breaching conditions of their licence.

"It is definitely not easy to lead a law-abiding life on release, particularly with little money and little support."

Last year, Justice Secretary Chris Grayling announced proposals to end automatic release at the halfway point for those serving prison sentences for certain offences including the most serious child sex offences and terrorism-related offences.

And so the debate around parole goes on.

"These arguments come around and around and around...arguments made years ago are just given new clothes and it will ever be thus," Prof Shute concluded.

- Published25 April 2014

- Published14 April 2014

- Published13 March 2014

- Published18 February 2014

- Published2 January 2014

- Published18 September 2012