Unsolved murders: The impact of not catching the killers

- Published

Some of the country's most notorious murders - Kate Bushell, Linda Bryant, Tuula Hoeoek and Claire Woolterton

The agony of not knowing who murdered a loved one is well documented. But what impact do unsolved murders have on the police officers trying to catch a killer?

Linda Bryant and Kate Bushell

Linda Bryant died in a field gateway from stab wounds to her chest, neck and back

In October 1998 on Cornwall's remote Roseland Peninsula, Linda Bryant was stabbed to death as she walked the family dog along country lanes near her home. She died in a field gateway from stab wounds to her chest, neck and back.

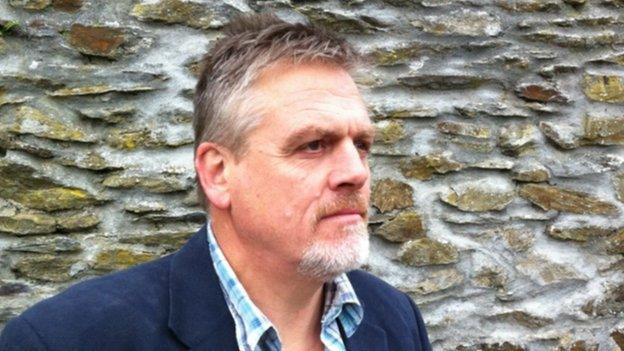

Chris Boarland, a retired Assistant Chief Constable with Devon and Cornwall Police, was in charge of the case and worked on it full time for 18 months.

Mr Boarland said he "always goes to where Linda was killed" when he visits the Roseland. "It's one of those cases which will never be closed," he said.

"This case was linked to the Kate Bushell killing which happened 12 months before... they are pretty unique cases nationally and internationally."

Chris Boarland, who is a retired Assistant Chief Constable, was in charge of the Linda Bryant case

Kate Bushell's body was discovered by her father just 300 yards from their home

Kate, 14, had her throat cut while she was walking her neighbour's pet dog near her home in Exwick, Exeter. Her body was discovered by her father just 300 yards from their home in 1997.

"All the advice from our profilers was people who kill like this have an offending history," added Mr Boarland. "They might be able to go for a while without committing further offences but they won't be able to go indefinitely."

But the former detective is not aware of any other crimes similar to the two murder cases. "Where is that person? Are they dead? Are they in prison? I can't believe they are living a normal life. It is a real mystery.

"For the family, you feel accountable - this destroyed their lives. You want these people off the streets. They're [the cases] never far from your mind. It's part of my life as well.

"For me personally, the Kate Bushell and Linda Bryant murders were horrible crimes and certainly stand out in my mind." His failure to catch the killer caused "a lot of sleepless nights" in the early days.

Since then, he has reflected on the cases a lot and still does to this day. "I'm very happy we ran a very professional, detailed investigation. But, of course, with a massive murder inquiry, the worry is always that we missed something. It's always on your mind to some extent.

"I don't think even in 16 years there were things they do now that we should have done then. All the evidence is in the bag, we've just got to get the right trigger to look in the right place and hopefully find the person who committed these horrendous crimes."

Claire Woolterton

Police said Claire Woolterton had been sexually assaulted

In 1981, the naked body of 17-year-old girl Claire Woolterton was found by the River Thames in Windsor. She had been sexually assaulted and her throat had been cut.

"It was a full-scale murder investigation and at its height there were up to 60 officers working on it," said Peter Beirne, a detective on the case in 1981 and now the principal investigator of Thames Valley Police's major crime review team.

Yet the case remained unsolved for 30 years and laid heavy on Mr Beirne's mind and when he visited Windsor he would "think about Claire, what happened to her and more importantly who was responsible".

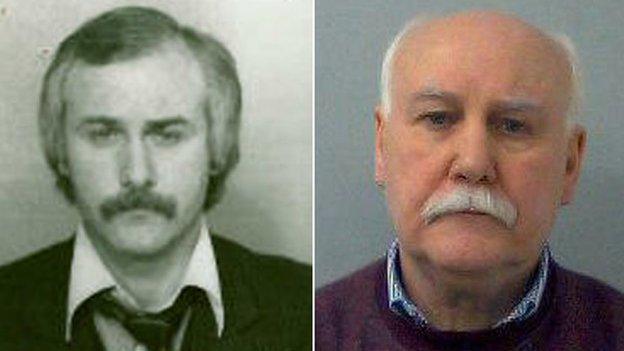

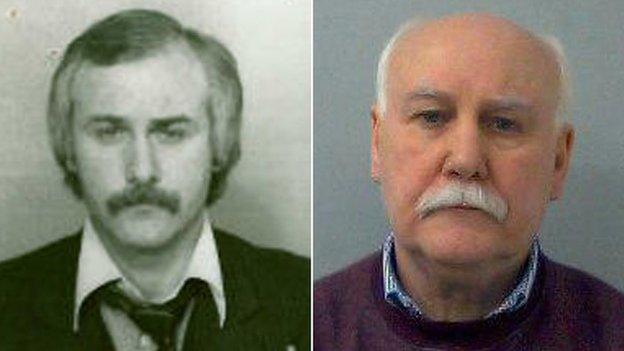

The case was reopened in 2011 when advances in DNA analysis helped convict Colin Campbell of murder.

Campbell was a convicted killer serving a life sentence for the manslaughter of Deirdre Sainsbury, from Greenham, in December 1984. In 2013 he was sentenced to life for murdering and mutilating Ms Woolterton.

When Campbell's DNA profile was found Mr Beirne, a retired officer working on unsolved murders, was "incredibly excited" and described it as "one of the highlights of my 39 years in the police".

"I was relieved [when he was convicted], I was happy for Claire's family, they had been through an awful lot." However, he added: "The hurt will continue for the rest of their lives."

For Ms Woolterton's mother and family, the three-decade wait to learn who had killed her daughter had a big impact.

Advances in DNA profiling and analysis eventually convicted Colin Campbell of the murder of Claire Woolterton

Claire Woolterton's body was found on Barry Avenue, Windsor, in August 1981

"After the initial grieving, which was traumatic and immense, you spend your life searching, not trusting, trying to cope with not only your life but your family's life, watching them in their grief and struggling," said Carol Woolterton. My eldest son suffered a nervous breakdown from which he never recovered."

When Campbell was arrested, she said the police were "very kind" and "broke the news very gently and gave my family a lot of support". She felt "shock, fearfulness and relief".

"I think I cried more than when it first happened," she said. "It opened up so many wounds. I didn't think I could deal with it all over again."

After Campbell was convicted she said she felt "upset, angry and relieved he wasn't able to do the same to anyone else". But she added: "Although it is all over, it doesn't bring Claire back."

Despite the case being closed, the emotional wounds caused by Ms Woolterton's death remain. "I worry about most things especially my family," her mother said. "It has brought back sad memories of Claire instead of the happy ones that I had learnt to live with."

Tuula Hoeoek

Police said a "heavy implement" had been used to kill Tuula Hoeoek

The impact of living in a small community, such as an island, can make it even more difficult for officers investigating unsolved murders to switch off.

In December 1966, the body of 20-year-old Tuula Hoeoek was found at the entrance to a field at Rue Laurens in St Clement, Jersey.

A "heavy implement" had been used to kill the Finnish au pair. "Her head and face had significant injuries but the motive for the killing was - and still is - unclear," said Ch Insp Lee Turner, who has worked on the case since 2012.

Over the decades the police have eliminated "many people" from the investigation but have had no firm suspect.

Tuula Hoeoek was last seen waiting at a bus stop in Georgetown

The Finnish au pair's body was found at the entrance to a field

Miss Hoeoek was last seen waiting at a bus stop in Georgetown in St Saviour at about 20:00 GMT on 30 December 1966. Police think she accepted a lift from somebody but she was not seen again until her body was found.

Ch Insp Turner said he felt a "huge sense of responsibility but also a huge sense of pride" working on the case.

"It is extremely difficult to switch off on leaving work in the evening. In fact, for me, some of the clearer thinking came from time away from the investigation room.

After working in Jersey in 1965 Tuula Hoeoek returned the following summer

"For me, it was impactive but not detrimentally so, living in a small community with almost daily reminders of aspects of Tuula's life [which] does keep the matter very much at the forefront of my mind.

"The ambition was for all of us to solve it and I still hope one day we will."

Ch Insp Turner contacted Miss Hoeoek's family in 2012 ahead of a fresh appeal and reinvestigation.

"They were reassured the police hadn't given up and her mother, who is in her 90s, still hopes her daughter's murderer will be found," he said.

"Knowing that the family still has not had closure on this tragedy for nearly 50 years provides further motivation for seeking answers they've painfully awaited for so many years."

Despite about 50 people coming forward with fresh information, her murder remains unsolved.

However, the States of Jersey Police said they had a "better understanding" of Miss Hoeoek's life in the island and it had "helped identify viable and fresh lines of inquiry and persons of interest".

"I was always hopeful but also realistic," said Ch Insp Turner. "The challenges were significant and I made this clear to the family.

"We have had to change our investigative mindset. If it happened tonight there are things we would do differently compared to 1966."

Supporting the officers

Dozens of police officers from across the country have contacted the charity Support After Murder and Manslaughter during its 15-year history, said Rose Dixon, the organisation's head.

She said that despite their job title "we must remember police are humans" and they "need to offload" and talk to someone about their feelings.

She said cases which replicate their home setting, such as the murder of a 14-year-old boy, if the officer has a child of a similar age "can be particularly difficult".

For the loved ones of the victim, not knowing who the killer is and why they died can be one of the most difficult things to come to terms with, she added.

- Published4 December 2013

- Published12 July 2013