How will UKIP's sums add up in the Midlands?

- Published

- comments

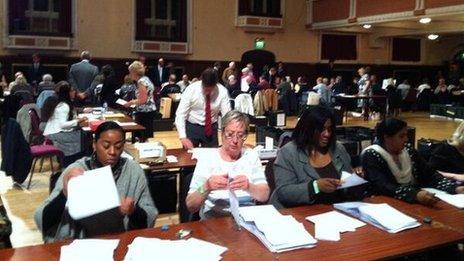

UKIP saw considerable success in the West Midlands after winning 428,010 votes

As Parliament returns after a Whit Recess consumed by pre, post and future-election fever, what are we in the Midlands to make of UKIP's showing in polls which produced no changes of party control whatsoever in any of our 18 local authorities?

Having promised "a political earthquake", Nigel Farage finds the surface landscape of local government in this region remains undisturbed.

UKIP were, nevertheless, the undisputed winners of the European elections.

Their 31% share of the vote was up by over 10% compared with 2009. And with a total of 42 councillors in district, borough, and county councils they have established themselves as a significant force beneath the headline numbers.

'Turning point'

Eleven of their councillors are concentrated in Black Country authorities, with Dudley emerging as their most important local power base. They also polled strongly in Cannock, Newcastle-under-Lyme and Redditch.

So if not quite the promised "earthquake", perhaps a more apt description comes from the first of UKIP's three West Midlands MEPs to be elected.

Jill Seymour MEP said "it's a turning-point" for the party.

We will know whether or not she is right only after next year's general election, now just eleven months away.

Remember, UKIP had polled strongly enough to secure two seats in 2009 only for their share of the vote here to shrink back to 4% in the following year's general election.

Birmingham City Council, led by Sir Albert Bore, remained under Labour control

So why does it feel different now?

For a start, UKIP secured three seats this time, confirming them as undisputed West Midlands winners.

But it is also because of the multi-party environment ushered in during this era of coalition politics.

The days when elections could be visualised with computer graphics showing blue or red tidal surges may be a thing of the past.

Nowadays it's not just about two main rival parties interacting with each other; it's a more complicated picture in which a complex of parties exerts a variety of gravitational pulls in different directions.

Predicting electoral outcomes in a region so chock-full of marginal seats can be fraught at the best of times; all the more so now there are almost 30 local seats where Labour and the Conservatives are vying with each other in pursuit of a Commons majority.

But introduce added complications, like the differential impact of UKIP on the other parties and the potential redistribution of Liberal Democrat votes, and you can see why so many of the conventional pre-election calculations fly out of the proverbial window.

UKIP won three council seats from the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats in Dudley

Simply weigh the votes and there is no question the Conservatives are hit hardest by the UKIP "surge": their tally of MEPs was reduced from three to two and they lost seats on most of the councils they contested.

But apply the numbers to council areas which roughly (or precisely) correspond to key parliamentary seats and you can see why it was Labour who ordered a post-mortem in the immediate aftermath.

Tamworth Council, a prime Labour target in a key parliamentary marginal seat, remains under Conservative control.

In Walsall, described by Ed Miliband as a must-win authority, Labour fell one seat short of an overall majority.

And the party will also have been disappointed that Worcester and Gloucester, both important general election targets, also remain under no overall control.

It is no accident that these are all places where UKIP put up a strong showing.

And finally.....

For the Liberal Democrats, despite their internal ructions after their expected poor showing, there were some notable crumbs of comfort here.

They retain their overall majority in Cheltenham, the one local authority they control here, even after half the seats were contested, much to the delight of the town's Liberal Democrat MP Martin Horwood.

They polled respectably in wards in and around the Birmingham Yardley constituency of his parliamentary colleague John Hemming.

Significantly, these are both traditional Lib Dem areas where support has grown, almost organically, and enmeshed over many years into local communities: we used to call it "pavement politics".

So the lesson could be that the party needs to go back to its roots.

But that would undoubtedly be interpreted as a rejection of Nick Clegg's vision of a modern, professional, technocratic party equipped for its role as a perpetual party of coalition government.

Put all this together, and you can see why next year's main event is shaping up to be, by far, the most unpredictable of all the nine general elections that I will have covered.