Hidden art: North East sculpture you have to hunt out

- Published

North-east England is home to hidden treasures you can only see with some effort, or by accident. But what is the point of tucking art away?

In a field on the outskirts of a Northumberland town there is a spoon.

"I would say that's a very logical place for a spoon to be," maintains its creator, Bob Budd, external, pointing out that fields are where food is produced.

At about 15ft (4.5m) high it is big for cutlery. It might be exposed but it is very difficult to find, via an underpass that takes some determined circling to locate.

Eat For England was erected in 2006, as part of a Lottery-funded art trail, external. Mr Budd calls it a "carrot" to entice people into the countryside.

Are you aware of hidden art near you? Please let us know at england@bbc.co.uk

If it was supposed to be easy to find "you'd put it in the middle of Cramlington" - a few miles to the north - he says.

But why not place it somewhere where lots of people will stumble across it?

Newcastle University's head of fine art, Andrew Burton, believes there is "always pleasure in unexpected discovery".

"There is an excitement or frisson about placing a work somewhere where it will really have to be sought out, so that the hunt becomes part of the overall experience," he says.

This frisson is something the cycle charity Sustrans has used in an effort to raise its profile.

Cows made from old bits of JCB diggers at Beamish in County Durham are among a whole collection only visible to people actually on the Consett-to-Sunderland cycle route.

The charity's North East regional director Bryn Dowson says the works "provide talking points, iconic images and add a sense of discovery".

It is a strategy that works, says Prof Burton, citing a project in Denmark, external for which he made a sculpture, external.

"Artworks were placed along what would normally be a fairly unremarkable stretch of the coast - it attracted 400,000 visitors in just a few weeks."

That, according to the project's organisers, is compared with a normal annual average of 250,000.

Four years ago Middlesbrough Council and Groundwork North East decided the local industrial estates could do with a spot of "enhancing" to celebrate the area's "rich industrial heritage".

The resulting collection of outsize tools has prompted something akin to a treasure hunt on Facebook, as people try to find the full set, external.

It might be giving the game away to say Andrew Mckeown's, external hammer and nails are at the junction of Sotherby Road and Murdock Road, but there are more nails, a set square and a pencil to find - and rumours of a screwdriver.

"There is certainly a thrill in chancing upon things," says Prof Burton. "It becomes somehow a more personal and charged experience.

"I don't think art encountered in this way would be greeted with the same scepticism that sometimes attaches to art in the gallery."

Those galleries are not averse to hiding things, either.

"Most of the Tate's collection is never on display" and many private art collections are kept in bank vaults or the "inaccessible depths of mansions", Prof Burton points out.

'Not made to not be seen'

County Durham blacksmith Graeme Hopper is well known for his larger works, such as Sunderland's metal men, but many more of his pieces can be found in unlikely places.

He said: "It is not unusual for art to be hidden, we get enough fame and glory for our art, it's more exciting for people when they stumble across something they were not expecting."

Helen Marriage, a director of Artichoke, the arts company behind the Lumiere Festival in Durham, said artworks may sometimes be hard to find but they are not hidden.

She said: "It's not made to not be seen but it is made to be set in a particular place that will add to the experience by its discovery."

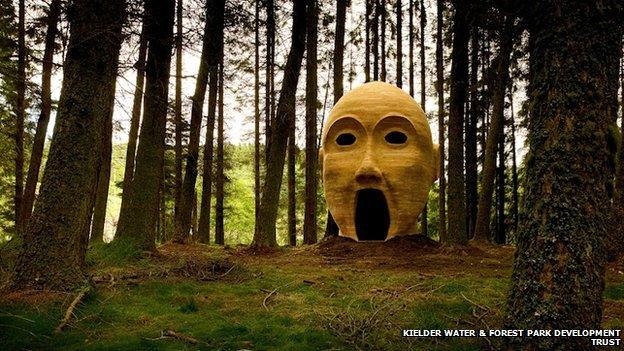

Considering it is a giant wooden head made from 3,000 pieces of timber, Silvas Capitalis, external is unlikely to fit in anyone's basement or bank vault. Huge, but tucked away in Kielder Forest in Northumberland, it rewards the determined with shelter and the view out of its eyes.

Like Kielder's "Skydome" it has to be "hunted down", says Prof Burton.

"It's remoteness is certainly part of its meaning."

So does location matter? Is it less meaningful if it is easy to find?

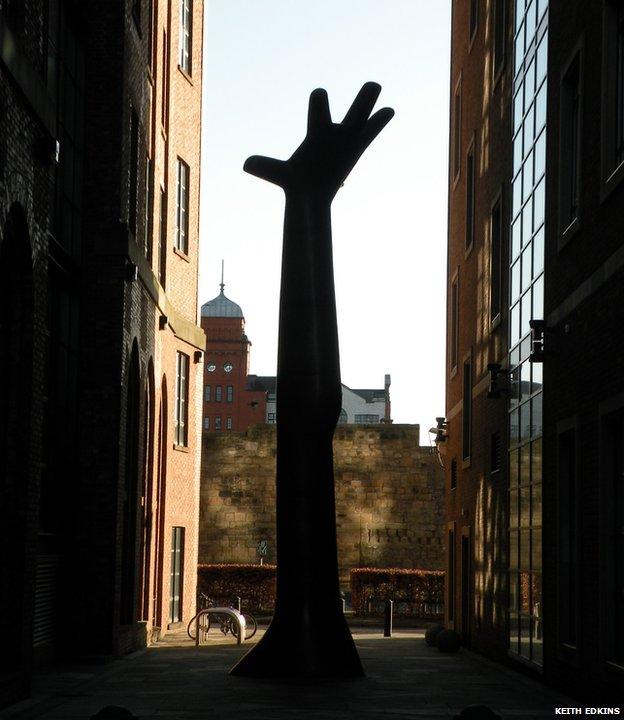

Kenneth Armitage's giant hand, Reach for Stars, used to be tucked between two offices, down a cul-de-sac in Newcastle. It was a secret treat for the, relatively few, people who knew it was there.

Professor Burton believes it "draws attention to a space that otherwise wouldn't be noticed or thought about much, and animates it in a certain way".

"Squeezed between those two buildings, you could see it as a rather desperate gesture, rather than aspirational, which is probably what it's supposed to be."

Adding to the excitement, it recently disappeared. However, it will reappear - in plain view this time - at the Crucible2 exhibition at Gloucester Cathedral, external in September.

Jane Buck, director of curators Gallery Pangolin, said they had spent some time choosing an "imposing position" for it.

But will it be the same, out in the open?

"Reach for the Sky will certainly have a different meaning sited outside Gloucester Cathedral," Prof Burton believes.

"I don't know that it will be so much about it being in the open - although that will make a big difference of course - but context is everything and I should imagine the religious overtones will be inescapable.

"Definitely it won't be chanced upon."

- Published10 July 2014

- Published1 September 2012

- Published13 March 2014

- Published24 December 2013