Birmingham tunnels: How to take pressure off city's roads?

- Published

Last summer, traffic queued to follow diversions on the A38 into Birmingham, although generally the disruption was far less than expected

As Birmingham's tunnels prepare to close for a second summer, could an alternative form of public transport ease the load on a city so dependent on the car?

Every day about 85,000 vehicles use the St Chad's and Queensway tunnels, which have taken the A38 into the city centre for the past 40 years.

Public transport plans in more recent years have focused on upgrades to New Street station, improvements to cycle lanes and paths, as well as an expensive, but limited, extension to the Midlands Metro tram network.

But could the UK's second city lead the way in public transport and are there other alternatives to trams, trains and buses?

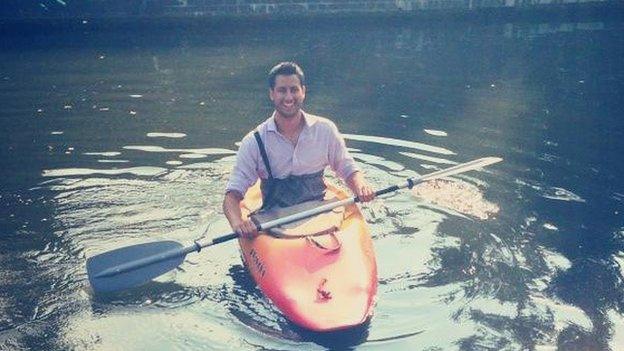

Canals

Mike Bandar has been kayaking to work for almost a year

Birmingham famously has more miles of canals than Venice, so could they provide a cheap way of commuting into the city and beating the traffic?

Mike Bandar is, as far as he's aware, a lone commuter on Birmingham's canals.

"People don't appreciate the extent of the canal network underneath us," he said.

"Sadly I've never seen any other kayakers on the canal, mainly just cyclists and runners on the towpath."

He started kayaking the mile or so from the Jewellery Quarter to Birmingham Science Park in Aston almost a year ago and apart from bad weather has kept it up.

"The hardest bit is walking down Great Hampton Street and Constitution Hill with my kayak. I get more funny looks doing that than once on the water," he said.

At work, the kayak gets parked in the cycle racks until home time.

The speed of travel, however, is perhaps the biggest barrier for anyone living further from work than Mr Bandar. The speed limit on canals in England and Wales is just 4mph, making it barely faster than those walking on the towpath and slower than cyclists.

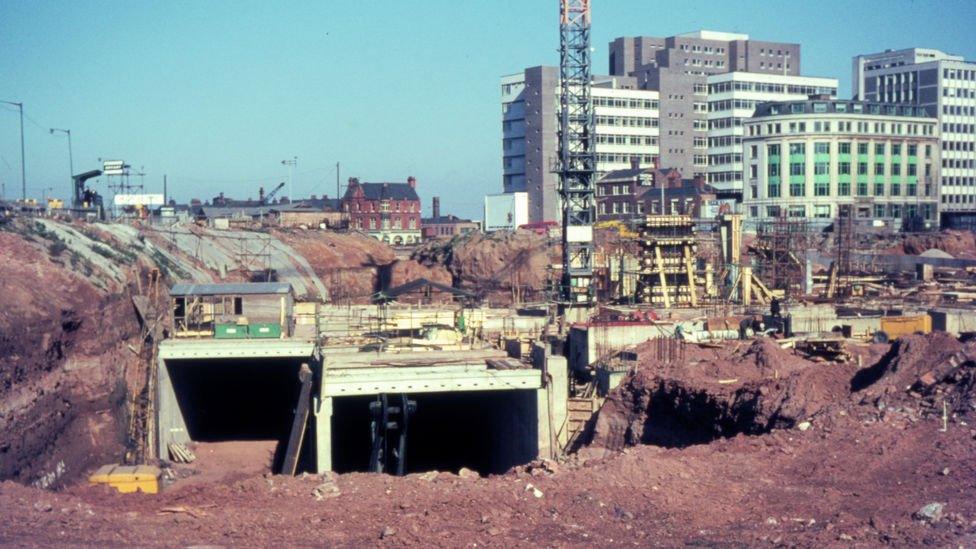

Underground trains

Could Birmingham benefit from an underground?

"The best solution, of course, if cost was no issue at all, would be an underground," transport expert Dr Pat Hanlon, from the University of Birmingham, has said.

"I once came up with a figure-eight system under Birmingham, with trains running in both directions," he said.

While a very real option 50 years ago, Dr Hanlon suggested "nobody would seriously consider that today financially".

"The costs would be unbelievably high. The cost of rediverting the utilities under the streets alone would be enormous," he said.

In November, Birmingham's Mobility Action Plan - a green paper outlining transport options over the next 20 years - described an underground as "extremely expensive and unlikely to be viable".

That has not stopped local politicians from proposing a system similar to that in London, Glasgow and Newcastle.

But for Derek Palmer, head of sustainable transport at the UK's Transport Research Laboratory, the problem for Birmingham is that at the moment Birmingham it is not big enough to support an underground, given the expense of building it.

"In London, you get the passenger numbers [to make it viable], but in medium-sized cities such as Birmingham you would struggle," he said.

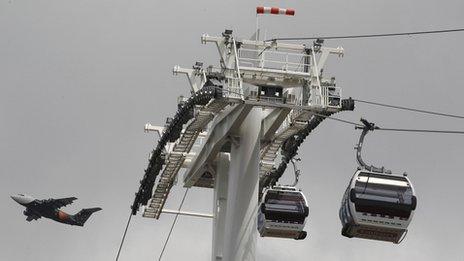

Cable Car

London's Emirates Air Line cable car opened in June in time for the Olympics

In December 2012, Midlands transport authority Centro said it was considering building a cable car system to link New Street, Moor Street and Curzon Street railway stations.

The system was expected to be similar to the £60m cable car across the Thames in London.

Centro, however, said the idea was quickly dropped as not being viable, mainly for financial reasons.

Transport expert Mr Palmer said there were other problems with cable cars, despite their success in a handful of cities around the world, such as Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil, or La Paz, in Bolivia.

"We don't really like high-level infrastructure [in Britain], because of the visual impact. Cable cars also have problems with capacity," he said.

Mr Palmer said cramped UK cities also made it difficult and expensive to fit supporting structures.

"Our highways are also quite narrow, quite bendy, and fitting a fixed track system within that is never going to be easy, even if it's possible.

"The problem is our cities have grown up over many years and have not been planned around transport."

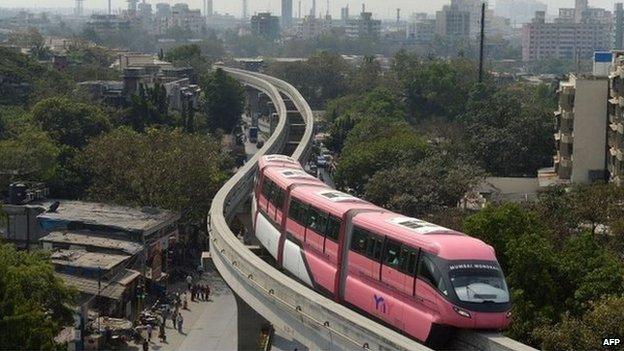

Monorail

Mumbai is one of the latest cities to build a monorail

The elevated line - which is similar to a monorail but with two tracks - running between Birmingham International railway station and the airport, is one of just a handful in the UK, so is there a case for making them as much a part of Birmingham as the Tube is a part of London?

Monorails have been a key part of some world cities for more than a century, yet in Britain are largely considered quirky tourist attractions, such as those at Chester Zoo or Chessington World of Adventures.

Proposals for a Birmingham city monorail were put together in 2008, with the Greater Birmingham Monorail Company formed to champion it.

Businessman Neil Maybury, one of those behind the scheme, said an outline feasibility study suggested that - at a cost of about £30m per km - it was cheaper than many other options and could carry up to 40,000 passengers an hour.

He described an elevated track for Birmingham as "viable" and a "realistic and world-beating option for solving the long-term traffic problems" in the city.

Mr Palmer, however, said they faced many of the same problems as cable cars, including their visual impact and the space needed to build supporting structures.

The Greater Birmingham Monorail Company said plans were "still very much alive"

Birmingham's 20-year transport consultation document suggests the city is at something of a cross-roads, although no direction offers a cheap solution.

If trams represent the best option, at least for the next decade, Dr Hanlon said he believed Birmingham needed to make a serious investment and ensure they were at least well-connected across the city.

"Manchester is streets ahead of Birmingham. They went for trams at an earlier stage, when Birmingham should have. It's a long, long way behind."

- Published3 February 2014

- Published26 December 2013

- Published20 July 2013

- Published7 November 2013

- Published6 August 2013

- Published6 December 2012