Aww-some animals: Why do baby mammals melt our hearts?

- Published

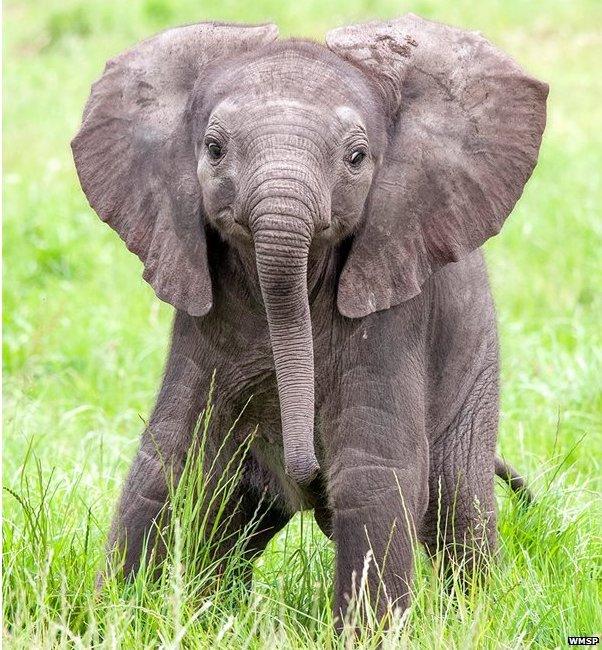

A newborn elephant at West Midlands Safari Park recently pressed a "cute button" across the world when its picture was shared on social media around the world. But why do photos of young animals pull on the heartstrings so much?

It is a well-known phenomenon frequently exploited in marketing. It is arguably not rational to choose your insurance based on an anthropomorphised meerkat or your toilet roll because you like puppies.

But emotional advertising works. Cuddly creatures turn cute into cash.

Baby animals have the edge - fubsy lion cubs are cute - but their adult counterparts are, no matter how handsome, menacing.

There is an obvious evolutionary explanation as to why we are drawn to human young - they need looking after or our species will die out.

But why do we have the feeling towards most baby mammals?

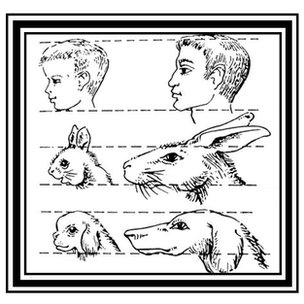

Nobel prize-winning, external Austrian academic Konrad Lorenz, external (1903-1989), who studied the evolutionary and adaptive significance of human behaviours - human ethology - pointed out many animals, for reasons entirely unrelated to enticing humans to be their caregivers, possess some features also shared by human babies but not adults: Large eyes, snub nose, bulging forehead and retreating chin.

Lorenz believed we are tricked by an evolved response to human young and we transfer our reaction to the same set of features in other mammals.

Anthropologist Andrew Marlow argues this reaction boils down to the way we, as humans, develop.

He suggests the bar for triggering the nurturing impulse is very low in humans, because human babies are ill-equipped to survive and need an enormous amount of looking after.

"It is partly an evolutionary battle between the pelvis and the cranium," said Dr Marlow.

"We are the only animal which walks exclusively on two legs. It freed our arms for using tools, weapons and gathering food. But the trade-off is that to accommodate our bipedalism, external, pelvises shifted position and became narrower.

"A modern woman is not physically capable of giving birth to anything larger than the head of a baby.

"Therefore the human brain has to develop a lot after birth, rather than in utero.

"Human babies are very vulnerable."

Lorenz pointed out we judge the appearance of other animals by the same criteria as we judge our own - although the judgment may be utterly inappropriate in an evolutionary context.

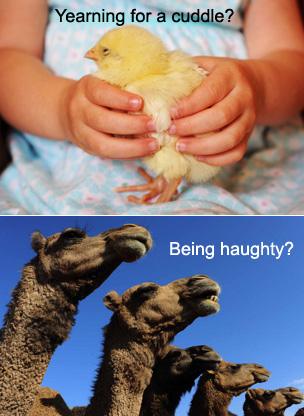

For example, new born chicks - despite appearances - are probably not yearning for a cuddle; and camels, with their noses in the air, are possibly not actually haughty.

Even aquatic creatures provoke the response - many of us see a dolphin, with its bulbous forehead and smiley face, as "cute". Conversely, a shark, which is not a mammal, seems to have a cruel mouth and mean eyes.

Nothing is inherently attractive or ugly, argues evolutionary biologist Simone Fellowes.

"It is our response which interprets it so. If babies began being born with long noses and narrow heads, or even horns, we would start to find those features appealing.

"In a more distilled way, it is why parents tend to believe their own offspring are more attractive than other babies.

"There is an inherent instinct to preserve our own lineage. With a narrow focus, it means our own specific DNA. A wider focus means all human young. An even wider focus means all mammalian young."

It means that although we are unlikely to confuse an infant human with a seal pup, we still have an impulse to care for the little fluffy creature with its big, imploring, black eyes.

This desire can even go as far as inanimate objects, external.

Cars marketed as "cute", such as the VW Beetle or Mini Cooper, have rounded bodies, prominent headlights and a short front end - or a chubby tummy, big eyes and a snub nose.

"This is deliberate," said designer Ben Crowther. "Especially in a quickly-growing market of female buyers, friendly [looking] cars are increasingly popular.

"It follows on that a significant proportion of these cars are given nicknames, further anthropomorphising them, bringing affections, and therefore loyalty."

With their tough grey skin, beady eyes, flappy ears and visually ridiculous noses, elephant calves should not appeal - but they do.

Again, it could be ascribed to identifying with human babies, said Mrs Fellowes.

Elephant calves, although not similar in looks to human young, have the elements of other behaviours - they look clumsy, playful, fragile (next to their craggy relatives) and innocent.

They stay close to their mothers, a survival instinct, but we interpret it as love.

"We see infantile behaviour, interpret it incorrectly, and transfer our affections," said Mrs Fellowes.

So when we find something adorably cute and aww over an elephant, or coo over a cub - we are not rationally responding to something which needs looking after; we could actually be compensating for a narrow birth canal and a poorly-developed brain.

Which, in terms of human survival, is a very cute trick indeed.

- Published9 June 2014

- Published27 November 2013

- Published23 August 2013