Are these England's last traditional craftsmen and women?

- Published

Craftsmen such as Jeremy Atkinson, from Herefordshire, are keen to pass on their skills

England's traditional crafts are in danger of disappearing, according to the few people still practising them.

Clog makers, basket weavers and wood turners have practised their skills for generations but the modern world increasingly has few needs for traditional master craftsmen.

Can the skills be passed on to the next generation before it is too late?

Owen Jones, 54, a 'swiller' from the Lake District

Swilling, or oak basket making, is a skill native to the area around Coniston, in Cumbria.

Swilled baskets can be seen in the illustrations of Beatrix Potter and were common until after World War Two, when materials such as plastic became popular.

The baskets were used down coal mines and even for carrying babies.

Swilling involves tearing thin strips from a trunk of boiled coppiced oak, then weaving them round larger strips, known as "spelks", which form the ribs of the basket.

Owen Jones is England's only full-time swill basket maker but runs classes to try to keep the tradition alive.

"When I first started 25 years ago, everyone in the local area knew what swilling was," he said. "Now there's a whole generation who have never heard of it."

He was taught to make swills in 1988 by John Barker, who has since died.

"He was a lovely, gentle man," said Mr Jones. "I think one of his motives for teaching me was that he was concerned it was a dying trade."

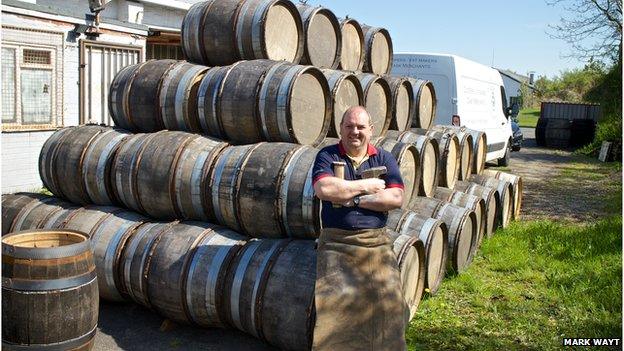

Alastair Simms, 51, a master cooper from Ripon, North Yorkshire

Alastair Simms is one of the few remaining master coopers in the country, but he has a feeling he is in a resurgent industry.

Large companies like Theakstons and Marstons employ less-experienced coopers, while the revival of real ale means many micro breweries are also interested in the craft.

Mr Simms learned his trade at Theakstons, one of a number of breweries that prides itself on using wooden, as well as metal casks.

The craft dates back centuries and Mr Simms said there was even a mention of a cooper being listed as "important cargo" in the insurance documents of the Pilgrim Fathers, early English settlers of North America.

He uses planks of English oak, bent into shape using fire or steam and held together with iron hoops.

He now supplies an assortment of breweries that are interested in how different types of barrel affect the taste of the ale stored in it.

"I did think about doing other jobs but getting involved with micro breweries has made it interesting again," he said.

Robin Wood, 49, a wood turner from Edale, Derbyshire

Robin Wood, a forester, says the traditional craft of turning wooden bowls on a pole lathe dates back to neolithic times.

"It's hard, physical labour but it's also very wholesome and fulfilling."

He built his own lathe out of fence posts and read numerous books on the craft before taking it up.

He now produces just under 1,000 bowls a year, varying in size from small olive bowls to larger soup dishes.

"Until about 10 years ago, I was the only person in England doing this," he said. "I have now taught a number of people in this country and around the world."

Mr Wood has supplied bowls to museums, such as the Jorvik Viking Centre in York, and film sets, including Ridley Scott's production of Robin Hood.

He is also chairman of the Heritage Crafts Association, which seeks to promote and preserve such skills.

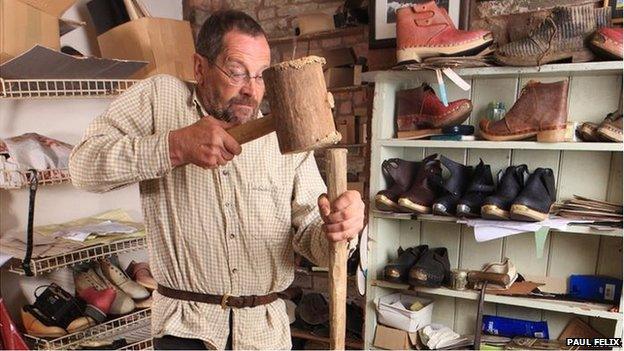

Jeremy Atkinson, 61, makes hand-carved clogs in Herefordshire

Jeremy Atkinson, who has made clogs from sycamore blocks since the 1970s, believes there is a bit of snobbery attached to the shoes.

"Most of my sales are in America," he said. "A lot of people in England seem to think they are shoes for northerners."

Mr Atkinson, from Kington, believes he is the only person in the country using traditional techniques to make the shoes from wood and leather.

"The older techniques all work," he said. "After all, people had several hundred years to get them right.

"Nowadays they have been largely forgotten. I make them for people who want something different.

"I make them for film sets and tree surgeons and people who just fancy them.

"They are leftovers from another age."

Sarah Page, 58, a trug-maker from Sussex

Trugs, baskets for harvesting food or collecting grain, have been made in Sussex for 200 years.

For Sarah Page, it was a business that came with the house she and her family bought in the 1990s - Coopers Croft in Herstmonceux.

"My three children were at school and I was looking for something to do," she said. "Trugs had been made here since 1899.

"There is a great tradition of trug-making in this village. It's like trug Mecca."

With the help of some of the older villagers Mrs Page learned the techniques of making trugs, which have a sweet chestnut frame and willow boards.

"It takes about five years to [learn how to] make them with enough speed and quality to be viable," she said.

Mrs Page is the last trug-maker left in the village and she knows of only six other people who can make them.

"I think it will die out, unfortunately," she said.

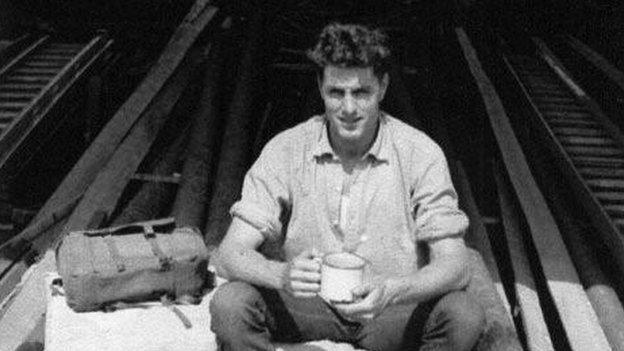

Stanley Clark, 75, wooden ladder maker (retired) from Northampton

Stanley Clark trained as a wooden ladder maker but retired from the trade 20 years ago.

"It was the trade I learned as a young man but aluminium ladders came in in the 1960s and 18 months later, nobody wanted the wooden ones," he says.

"We used to make more than 2,000 ladders a year, made to measure ones, out of Colombian and Norwegian pine.

"Once the aluminium ladders came in, I made the odd one for a window cleaner who wanted a made to measure ladder but that was it. There are now only a few people left who can make the wooden ones."

Do traditional crafts have a future?

But how much would it matter if such archaic skills were simply to die out?

Mr Wood, from the Heritage Crafts Association, says it would matter enormously and points out other countries, such as Japan, are passionate about preserving such traditions.

"Over the last 10 to 15 years, quite a lot of the folk we used to work with have retired or died without passing their skills on," he said.

"The last rake maker to use locally-sourced English wood was a man named Trevor Austen from Kent. He died and his workshop was broken up.

"I believe these skills are part of our heritage, as much as the historical buildings and wildlife we seek to protect.

"We need to see they are passed to the next generation."

Charlie Harrison commissioned an audit of endangered crafts for Furniture Village, which is campaigning to preserve such traditions, external.

"If they were to disappear, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to recreate the unique skills behind these centuries-old forms of craftsmanship," he said.

"Though the world has changed, and many of the marketplaces for these crafts have altered too, they are so much more than charming curiosities: they are a living connection with our past."