On your bike: Will cycling ever work in our cities?

- Published

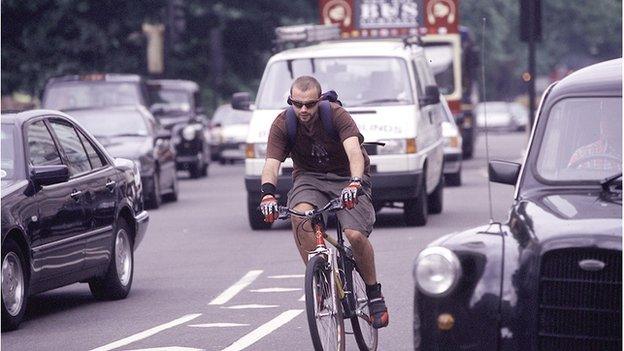

Edged out? Cycling in English cities can be a battle between commuters

As Angela Marlet cycles through the city to pick up her one-year-old son from nursery, she passes through a multi-coloured sea of bicycles.

"You are surrounded by all sorts of people of every age, for example children, mums with kids on their bicycles, businessmen and businesswomen, the elderly, migrants, tourists," she says. "Everyone is cycling."

Meanwhile, Ben Adams is also cycling through a city, on his way to work, but for him the experience is very different.

As he travels, he breathes in the traffic fumes of the hundreds of cars and lorries that pen him in on one side of the road. Not just that, but his eight-mile commute can leave him feeling a little vulnerable.

"On one occasion a van driver pulled alongside me and started yelling at me - I have no idea why," he said.

"I stopped, he stopped, he got out of his van and shoved me. Luckily, a passer-by started filming it on his phone and said, 'I think you should leave him alone, mate'."

In Amsterdam, cycling is widespread among people of different age groups, genders and backgrounds

The distance between the cities where Ms Marlet and Mr Adams live is some 200 miles (363km). Yet the separation between the attitudes towards the humble bicycle could not be more different.

While Ms Marlet lives in Utrecht, the fourth largest city in the Netherlands, Mr Adams, until recently, lived in London.

Both of them cycle every day, but for Ms Marlet the experience of commuting, at least, seems to be more enjoyable.

"I cycle to work every day and do my shopping on my bike," she said. "It is very safe to ride a bicycle during night or early in the morning."

While cycling is on the increase in the UK - thanks to sporting stars like Sir Bradley Wiggins - many would like to see more investment in making roads safer for bikes

For Mr Adams, while he loves cycling - "I love the freedom - and the wind in my hair," he said - the experience can be stressful and difficult.

"I lived in Germany for two years and, over there, cyclists are respected," he said. "Whereas over here you are an inconvenience on the road.

"I found cycling in London horrific. People get frustrated and when they pass you four or five times in their car or van and then you keep going past them, sometimes it boils over."

While in parts of Europe - Germany, Denmark and The Netherlands - large parts of the population regularly cycle, last year people in the UK made just 1% of journeys by bicycle, according to a Department for Transport survey, external published on Tuesday.

Ben Adams has lived in both Germany and the UK. He feels cyclists are "respected" more in Germany

While women make an average of seven trips a year by bicycle, men make three times more.

"My wife won't cycle in the UK," said Mr Adams. "She's too scared to go on the roads."

Experts say cycling is on the increase - partly inspired by the success of people like Sir Bradley Wiggins, Sir Chris Hoy and Chris Froome.

Louisa and Lydia Obadan use so-called Boris bikes in London - but say Nottingham, their current home, is not a city for cyclists

But while a high proportion of young, athletic men are keen to don their helmets and do battle with the 4x4s, there are concerns the wider population is being left trailing in their wake.

"Cycling can seem quite intimidating," said Louisa Obadan who regularly uses London's cycle hire scheme - the "Boris Bikes" - in the capital but does not cycle now she has moved to Nottingham.

"If you're in a car, you feel the four walls protect you. I think there are more guys who are willing to go out in the traffic on bikes."

"Women want to ride at their leisure - we're not competing in the Tour de France," added her sister Lydia. "I know women who would love to ride bikes but at the moment it doesn't feel safe enough.

"Nottingham is not a cycling city. The council does have a bike scheme but their bikes look quite rickety compared to the Boris bikes."

One British city that is trying to remodel itself as a cycling city is Bristol, where the numbers of women cycling have doubled from 2.3% to 4.6%.

The number of cyclists in Bristol is four times the national average. "We have more daily commuters using bicycles than Sheffield, Nottingham, Newcastle and Liverpool combined," said Tim Borrett from the city council.

The council has invested £35m to develop a cycling strategy and make cycling safer in the city.

Alec James, from Sustrans, a charity set up in the 1970s to promote cycling, said: "The key to normalising cycling in British cities is safety.

"That's the number one concern of people who want to cycle but don't. Cycling is actually quite safe compared to other forms of transport but public perception says otherwise.

"We also need a better quality of roads. Our road network is a hangover from a time when the car was king. Cycling needs to be a part of road design from the get-go - not tacked on later."

Mr James said he believes many politicians are waking up to the benefits of cycling - but not enough.

The Labour MP for Hackney, Meg Hillier, who sits on the all-parliamentary cycling group, said cycling needs to be considered "normal" for the vast majority of the population - and that starts with city planners.

"Central government has to crack the whip," she said. "Ultimately these things are delivered by local authorities."

She added segregated cycle routes - of the kind found in Germany and Holland - were the "Holy Grail of cycling".

But she added: "It's going to be difficult to achieve that in a lot of cities."

Instead she said she would like to see alternative routes for cyclists - such as through parks or along canals - created.

"Making cycling normal for everybody is about a popular movement - among cyclists and non-cyclists," she said. "If you were a cyclist as a kid and you loved it but you never ride a bike now, why not? Get in touch with your council or your MP and tell them."

Cycling charity Sustrans says cycling needs to form a key part of road design - and not be tacked on later

So is there hope for our cities? Could we ever rival the Dutch in their enthusiasm for two-wheeled travelling?

Sustrans believes it is certainly possible - but it may take some time to achieve.

"The Netherlands in the 1970s was very similar to Britain today," said Mr James. "Many people relied on cars and many of the cities were full of traffic.

"Then there was a wave of protests in a movement called Stop de Kindermoord (stop the child murder) after a sharp rise in the number of kids getting run over.

"There was a big public outcry against cars and the humble bicycle was chosen as a way to influence the Dutch government's transport policy.

"The legacy of that movement is the system the Dutch have today - but we are now 40 years on. I hope it doesn't take as long over here."

- Published14 February 2014

- Published8 August 2013

- Published9 June 2013

- Published4 November 2012