Scottish independence: The consequences for northern England

- Published

Norham Castle, on the English side of the River Tweed, protected against raids from Scottish reivers

If Scotland votes for independence on 18 September, the north of England will have a land border for the first time in centuries and will face the challenges and opportunities of having another country on its doorstep. What might the consequences be for northern England?

A little over 400 years ago, the challenges were different from those of today.

The borderland back then was a law unto itself - literally, with its own system of law and administration both sides of the border - designed to deal with a brutal population of "border reivers", meaning raiders, whose way of life revolved around theft and violence.

The reivers, who were both Scottish and English, operated as far south as the Tees and raided almost as far north as Edinburgh.

Back then, the complaint from English borderers was that they did not have the protection of their king against the Scots - and so they formed a common way of life with their cross-border neighbours.

Today the social links across the border endure and the gripe from many in the region is that the Westminster government does not give it the support and investment it needs to compete with Scotland, or with other parts of England.

Craig Johnston, who shares his surname with one of the great reiver families, is English but campaigning for a "yes" vote in Scotland.

He lives in Carlisle, the closest city to the border, where he used to be mayor and is now regional organiser for the RMT transport union for northern England and Scotland.

"Scotland has better arrangements for transport, student tuition fees and an altogether better agenda," he said.

He hopes independence in Scotland will energise debate about greater regional autonomy in England.

Why do some in the North East and Cumbria think they get a raw deal?

Research for the BBC in 2012 suggested Scotland was spending 76% more per head on economic affairs than its neighbour, north-east England

The north of England has seen its Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) scrapped and replaced by lower-budget Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), although critics said RDAs were inefficient and much of their money went to public-sector projects

Scotland has retained its equivalent agency, Scottish Enterprise, which some have credited with attracting business away from northern England

The government's proposed £42bn high-speed rail project HS2 will never reach the North East or Cumbria, although the government has said it will benefit the region indirectly

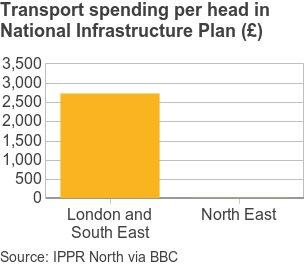

Analysis by the think tank IPPR North, external in 2011 concluded the government's National Infrastructure Plan allocated £2,731 of transport spending per head in London and the South East, in projects where public funding was involved, compared to £5 per head in the North East

The government has disputed the analysis, but the think tank has since maintained such a disparity exists, external

He cited underinvestment in infrastructure and the scrapping of the Regional Development Agencies (RDAs), which were used to help economic development, as ways in which northern England has not been well served by government.

Scotland, meanwhile, already has a stronger set of institutions and could be further empowered by independence, Mr Johnston said.

"What we need is one regional government across the North, including the North East, North West, Yorkshire and maybe areas like Cheshire," he said.

But the North East was offered a regional assembly 10 years ago and rejected it in a referendum.

Prof John Tomaney led the campaign for a yes vote in 2004.

He said: "One of the most compelling arguments made against the regional assembly was that it was going to produce more politicians.

The HS2 project will not reach the North East or Cumbria, but campaigners have said an independent Scotland could bring high-speed rail to the region

"I think we caught the first ripples of the waves of anti-politics, which have grown since then."

In contrast, he said politics was "alive around the referendum" in Scotland.

An institution recently set up to give the North East a stronger voice is the North East Combined Authority, a coalition of councils that can bid for government investment in transport and development projects.

Its leader, Simon Henig, who is in favour of the union, said: "In Scotland, because they have the Scottish Parliament, there are bodies there arguing for more powers."

But he said there was no public appetite for more politicians in England.

"That's why I think the current arrangement around a combined authority is the best way forward, because it uses the existing resources to make those same arguments," he said.

George Beveridge, a Scot on the English side of the border, chairing the Cumbrian Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP), agreed it was better to seek more powers for existing institutions.

There are fears in Cumbria that lower taxes in Scotland could cause "a flight of businesses across the border"

But he said he worried further powers for Scotland in the event of independence, or greater devolution following a "no" vote, would put northern England at a disadvantage.

He said lowering corporation tax, an expressed desire of the Scottish government, could cause "a flight of businesses across the border".

Mr Henig, meanwhile, expressed concerns about a reduction in Scottish Air Passenger Duty sucking business away from Newcastle Airport.

However, some in northern England are alive to the opportunities of working with an independent Scotland.

Last year the Association of North East Councils (ANEC) commissioned a "Borderlands" report, external, looking at the pitfalls and opportunities Scottish independence might present to the North East and Cumbria.

It concluded there were a number of areas in which northern England and Scotland could work together, based on common economic interests.

The report inspired a "Borderlands summit", external of councils either side of the border in April, hosted by Scottish Borders Council.

The Yes Scotland campaign has also suggested an independent Scotland might invest in high-speed rail links with the North, external. But despite the suggestions of cross-border co-operation, a coherent, region-wide strategy has not emerged.

The modern borderer

The road between Paxton and Berwick overlooks the Tweed

Every day, Julien Lake cycles five scenic miles from his home in the village of Paxton to his workplace in Berwick, on a road which overlooks the River Tweed and the Northumberland countryside beyond it.

His journey starts off in Scotland and ends up in England.

"Most people in the village travel to Berwick routinely, whether it's to the supermarket, the doctor's, or the bank," he said.

"It's a real mix of folk here. Some people identify as English and some as Scottish and there is also a sense of people being borderers."

Originally from just outside Sheffield, Mr Lake has lived in the borders for eight years and, because he lives a mile into Scotland, will get to vote in the referendum.

"It's great here. It's visually attractive, there's low crime. Employment can be difficult, but I'm lucky in that regard," said the 42-year old, who works for the Berwick Community Trust.

He said his mind was firmly made up over the question of independence.

"Maybe it makes sense if you live in Aberdeen or Inverness, where life is different, but here where everything's so integrated, it just doesn't make sense."

The report that spawned the Borderlands summit had a broad, strategic scope, consulting with people from Teesside to Edinburgh.

But the summit itself included only councils adjacent or in close proximity to the border, suggesting a narrowing of the initiative.

Meanwhile the formation of the North East Combined Authority and Newcastle's recent collaboration with cities in Yorkshire, Manchester and Merseyside over transport represent separate attempts from parts of the region to make their voice heard in Westminster.

Mr Johnston said: "The current attempts to give the North a greater voice are too fragmented. I don't think they're doing it anywhere near fast enough."

If the North East and Cumbria do find a strategy to improve their political and economic clout, the question is whether they focus on getting more powers and investment from Westminster, or, like their borderer ancestors, they gravitate towards a potentially empowered northern neighbour.

- Published3 September 2014

- Published2 September 2014

- Published9 September 2014