Fair is fair: How show-women were given a chance to thrive

- Published

The fairground has always been a place of innovation and some of its most famous acts were first performed by women

When you think of female fairground performers, you might picture the fortune teller, the knife-thrower's target or, perhaps, the bearded lady. But beyond the stereotypes, in its heyday the Victorian fair was one of the few places where women could forge independent careers.

In the 19th Century, women primarily belonged to the domestic sphere - either as wives and mothers, or servants, nurses and teachers.

So how is it that in a society where the average woman had limited prospects, show-women were able to subvert the norm?

"What I love about the fairground is it's genderless," said Prof Vanessa Toulmin, director of the National Fairground Archive (NFA) at Sheffield University.

"Females could be famous performers at a time when women couldn't even go to the theatre.

"They had property on the fairground, they owned rides, they owned shows, because the society was aligned to a community that worked together."

One of the earliest women to make their mark as a show-woman was Marie Tussaud.

The French sculptor arrived in London in 1802 and toured her waxwork shows on fairgrounds for 20 years before establishing herself in Baker Street in 1835, where visitors paid sixpence entry.

Today, with 19 sites worldwide, her legacy speaks for itself.

"Madame Tussaud is one of the most famous entertainers," added Prof Toulmin. "What other industry would have given her that opportunity?

"Being a showman or a show-woman isn't about gender, it's about ability. And if you're good showman or show-woman then the opportunity is there."

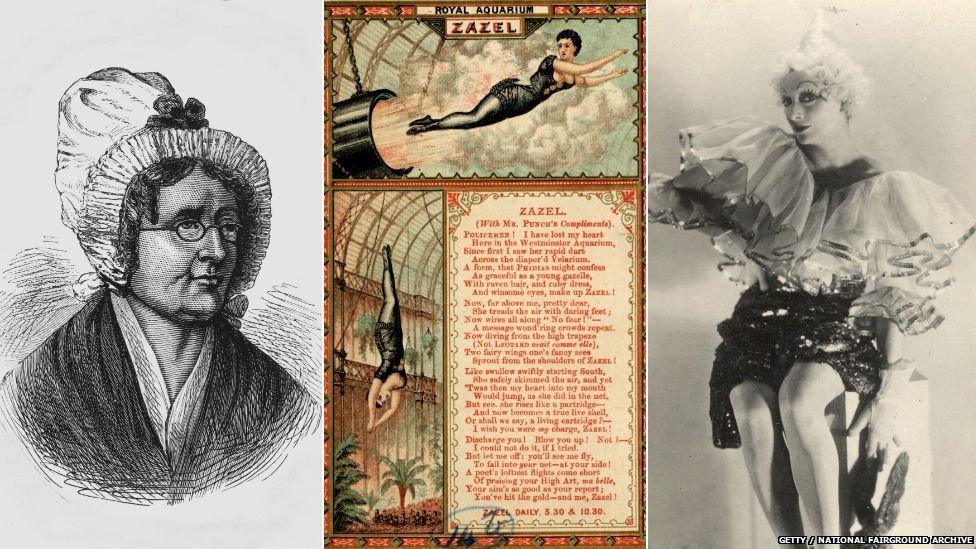

Madame Tussaud, Zazel and Lulu Adams all blazed a trail on the fairground circuit

The fairground has always been a place of innovation and some of its most famous acts were first performed by women.

Teenager Rossa Matilda Richter made history in 1877 when she became the first human cannonball.

The 14-year-old made her debut as 'Zazel' at the Royal Aquarium in London and went on to appear in France and the US.

But Dr Ann Featherstone, a guest lecturer in Victorian entertainment at Manchester University, argues Zazel was not necessarily chosen just for her ability.

"Zazel was about thrill-seeking," she said, "Men like to see women in dangerous situations because, I suppose, there's something quite erotic about it - seeing a woman in peril. So there was an exploitative element to it.

"What you saw was lots of leg, so there was a sexual element and that would have put bums on seats. It's far more titillating to see a woman shot out of a cannon than a man."

While show-women had opportunities to build a career in the spotlight, many chose to manage stalls, rides and the purse strings too.

"The thing about the fairground is it's about family, which enabled women rather than disabled them," said Dr Featherstone.

"Women were expected from a young age to be part of the family business, so they didn't discriminate, because women were important in making the whole thing work."

Sophie Hancock ran W S & C Hancock's travelling show during the late 19th Century alongside her two brothers. The business suffered a setback in 1913 during a suffragettes' riot in Plymouth, which saw the fairground destroyed by a fire.

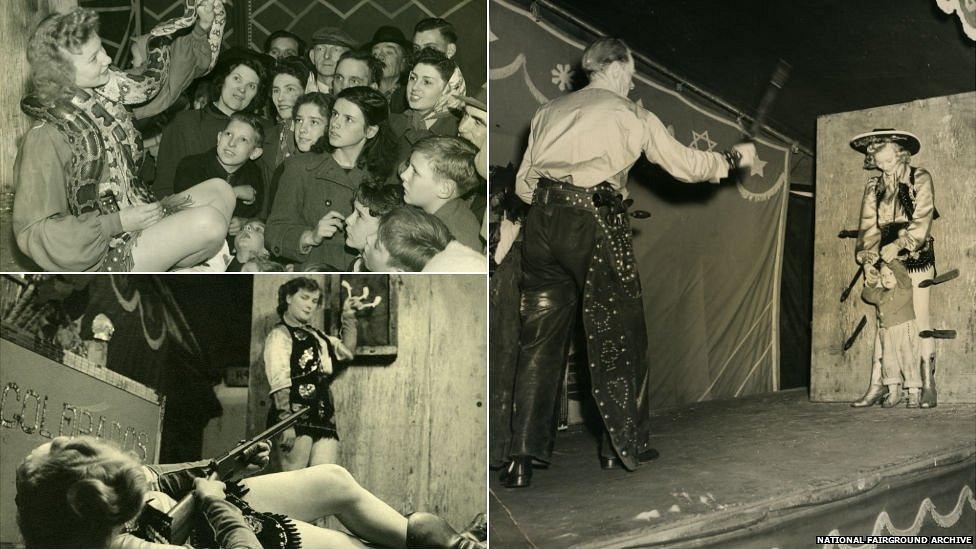

Florence Shufflebottom forged a career as a snake charmer and a sharpshooter

But, the firm was saved following a nationwide fundraising appeal, which saw the family-run fair return for a number of years.

"When she started there was no Showman's Guild and you had to run to get a pitch. One of the stories about her is that she could outrun any man, woman or policeman to get her pitch," said Prof Toulmin.

Dr Nicola Philips, from Kingston University, said most middle-class women worked in feminine trades such as, food, retail and textiles, while the working class would have been in domestic service or factory workers.

But until the Married Women's Property Act was passed in 1870, wives had no legal right to trade and it wasn't until 1907 she had full control over her earnings.

She said: "Almost certainly, if you lived on the margins [of society] it would give you more freedom, because it was profitable for the family unit and it was about survival.

"[Fairground women] were quite unusual because they were in the public and visibly controlling their own money and business. If upper middle-class women helped with the business, you wouldn't see them doing it, they would be doing it behind the scenes."

While it was commonplace for a woman to run the show following the death of a male family member, a career at the fairground was also a way for women to carry on tradition.

Lulu Adams followed in her father's footsteps to become one of the first female clowns to appear at Olympia in London in the 1930s.

She avoided grotesque make-up and wore a curled white wig and a glittery costume, appearing in top circuses before retiring in 1962.

By the early 20th Century, women could vote, but it would take several decades before legislation made it illegal to pay women less than men for the same role or to discriminate based on gender.

.jpg)

Prof Toulimn's aunt Brenda O'Connor was a famous contortionist

In the fairground world however, it was business as usual and women continued to make a name for themselves.

Florence Shufflebottom blazed a trail throughout the 1940s and 1950s as the star of the fairground - a talented sharpshooter who started out as a prepubescent snake charmer.

The carnival crack shot from Leeds was also the first to donate a box of family memorabilia to the NFA, which is now celebrating its 20th year.

"On the fair, women have always had work," said Prof Toulmin, who grew up watching her grandmother, mother and aunt become both successful proprietors and performers.

"It's part and parcel of what you are.

"There wasn't one woman in my family that didn't work, I worked from the age of 10 and so did my brothers and sisters. To me, in my community, it's a part of the job."