The industrial 'eyesores' we just can't part with

- Published

Clipstone Colliery's headstocks: What's the appeal?

When crumbling chimneys, mining headstocks and dilapidated factories come under threat of demolition, locals often spring to their defence, armed with petitions. But why do we get so attached to these often ugly vestiges of our industrial past?

Could the 200ft (61m) headstocks, which dominate the entrance to the former Clipstone Colliery in Nottinghamshire, form part of a mile-long zip wire?

Campaigners have suggested the pit, which closed in 2003, should become an East Midlands "Eden Project", external with the headstocks as a centrepiece.

A petition has been gathered, signed by more than 2,500 people to have them kept.

But are they an eyesore? Not, according to Denise Barracolough, who heads the Save Clipstone Colliery Headstocks campaign.

"I don't think they're ugly," she says. "They are magnificent iconic structures and there's such a lot of history attached to them.

"The headstocks are on the school uniform, the football club kit. People identify with them, people feel they have come home when they see them.

"If you demolish the headstocks you lose the village's identity and purpose."

A planning application, external was lodged in 2003 to demolish the Grade-II listed headstocks and power house. Twelve years on, it still has not been fully resolved.

Whether or not the campaign will succeed is difficult to predict.

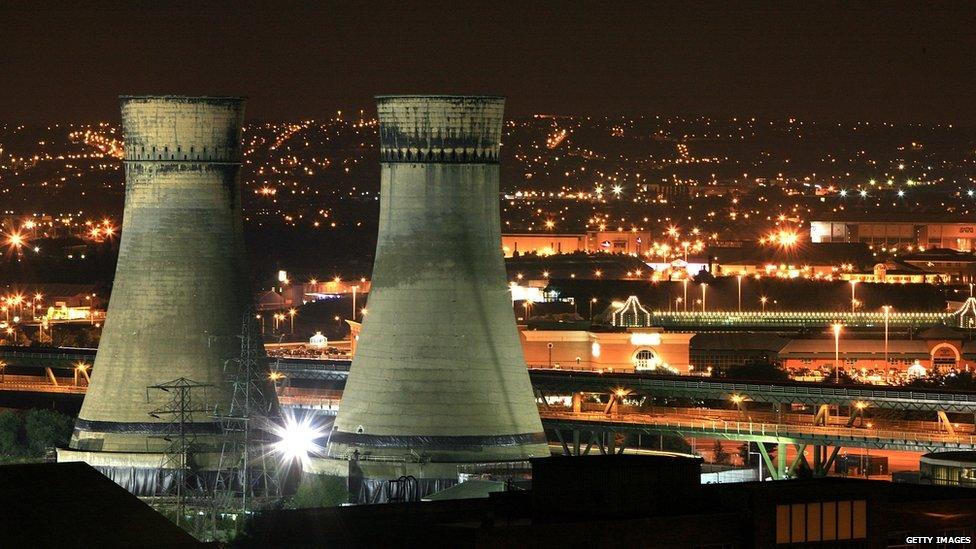

People power was not enough to save Sheffield's equally well-loved Tinsley cooling towers, which were demolished in 2008 when thousands turned out to see the "salt and pepper pots" come down in the early hours of a Sunday morning.

Tinsley cooling towers were demolished despite fierce local opposition

Somehow escaping demolition for 28 years after Blackburn Meadows power station closed, the 250-ft structures at the side of the M1 signalled to Sheffielders they were home.

More than 4,000 people signed a petition against the demolition and Antony Gormley, creator of the Angel of the North, said it would be "cultural vandalism" to knock them down.

"They are to the industrial revolution what cathedrals were to the Medieval world," he told the BBC at the time.

But owners E.On said they no longer served a purpose and had to go.

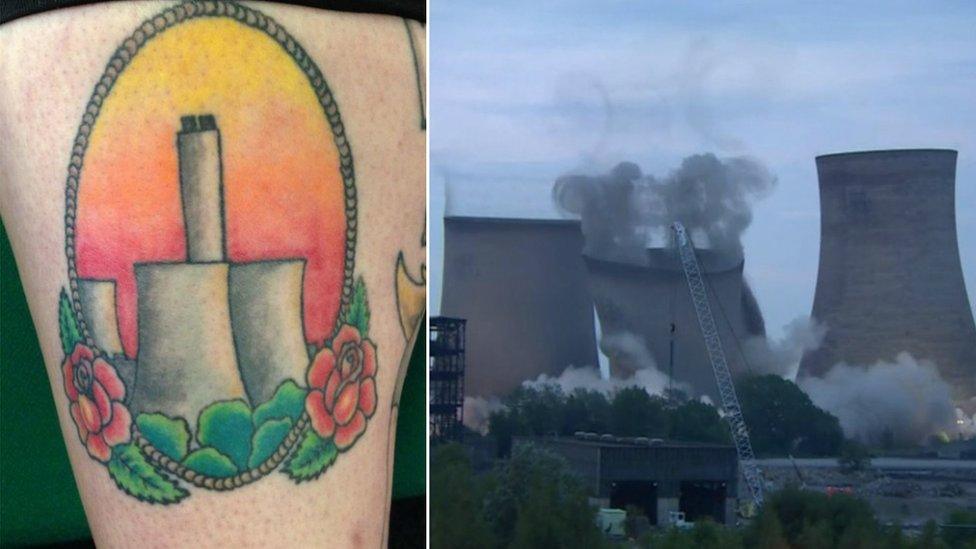

More recently, Didcot A power station saw three of its towers brought down. The coal-fired power station, which closed in March 2013, was previously voted Britain's third ugliest building but many were sad to see it go.

Kelly Green loved Didcot Power Station so much she had it tattooed on her leg

Kelly Green, who grew up in the Oxfordshire town, had an image of the towers tattooed on to her shin. She says people living nearby would miss the sight of the power station. "It still reminds me of my childhood and where I come from."

"Anyone passing by might think these buildings are eyesores but it's about familiarity," says Thomas Lane, editor of Building Design magazine, which gives out the annual Carbuncle Cup to the ugliest building in the UK.

"People become familiar with these structures. They become part of the landscape as a consequence. Local people become attached to them for those reasons."

Often, even strong links to the industrial past are not enough to save a building from the bulldozer, however.

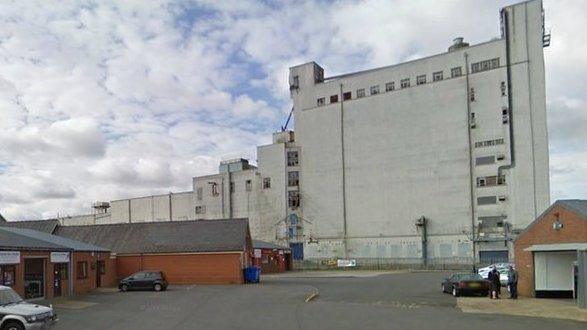

Some are deemed just too ugly to keep, such as the "concrete cathedral" that dominated the skyline of Louth in Lincolnshire.

The former malt kiln, built in 1950, was demolished in January to make way for an Aldi supermarket and has not been missed, according to the chairman of the local historical society.

Louth Malt Kiln was demolished in January

Despite the fact his wife and brother-in-law worked there, Martin Chapman says the building was becoming derelict and "looking untidy".

"You have got to move on in this world. You can't stand still - some things have got to go and Louth Malt Kiln was one of them."

Finding novel uses for iconic former industrial structures is a way to keep them relevant, according to Dr Anthony Streeten, planning and conservation director for English Heritage, who cites the example of Germany's Ruhr Valley.

A large number of "heavy engineering monuments" from the coal industry have been incorporated into the modern landscape, he says.

"They have perhaps a slightly more relaxed view of health and safety but they've created climbing frames out of them," he explains.

"Some people may have painful feelings towards the [Clipstone] headstocks - they may think, let's forget about this," he adds.

"Future generations may value it more. We think it's rare and distinctive."

Northampton Lift Tower has been brought back into use as an abseiling centre

In the East Midlands, a Grade-II listed tower - part of a former lift factory - has survived by becoming an abseiling venue.

The "Northampton lighthouse", as it was jokingly referred to by Terry Wogan, stands at 418ft (127m) and was built for Express Lifts in 1982.

The factory closed in 1999, and since 2011 it has been used by extreme sport fans. Last year the borough council gave permission for it to be used up to 24 times a year for abseiling.

Architecture critic for the Sunday Times, Hugh Pearman, takes issue with the notion that industrial buildings can be "ugly".

"Large-scale industrial buildings are landmarks which give distinctiveness to a place," he says.

"Power stations are especially good for this, which is why two of the greatest in London - on Bankside and at Battersea - are these days so admired."

Bankside has become the Tate Modern while Battersea, having been derelict for decades, is now being restored and converted as part of a huge redevelopment.

"Apart from the aesthetic value of the best examples, people relate to the relics of former industry because of the lives that were intertwined with them," adds Mr Pearman, who also edits the RIBA Journal.

"The chances are that if you live nearby, members of your family worked there - in a mine or a factory or power plant, say - perhaps going back several generations.

"This engenders pride - people feel they 'own' such places and feel affection for them."

- Published9 March 2015

- Published30 January 2015

- Published3 September 2014

- Published14 December 2012

- Published20 May 2011