Can you put a price on history?

- Published

Runnymede was the site of the historic sealing of Magna Carta 800 years ago, in 1215

Many consider Magna Carta to represent the foundation of modern democracy, but a political row has erupted over a council spending £1m to mark the 800th anniversary of its sealing. How much are we prepared to spend on our history?

The Queen, Prince William, Duke of Edinburgh, Princess Royal and other dignitaries have been gathering at what is essentially a field in Surrey.

Known as Runnymede, the field was witness to the sealing of Magna Carta and is seen by many as the birthplace of modern democracy.

Gathered dignitaries are being entertained with musical and spoken word performances, seeing the unveiling of a new piece of artwork and witnessing the rededication of the existing Magna Carta memorial.

But, some people have questioned the "spiralling" cost of the event - which originally had a budget of £100,000, but has ended up costing £600,000.

The artwork - 12 bronze chairs called The Jurors - has cost an additional £400,000, and all this had been paid for by Surrey County Council.

Runnymede is not currently a big tourist attraction, but it does have a Magna Carta memorial built by the American Bar Association

"No-one disputes that the signing of the Magna Carta is a significant moment in our history," said opposition councillor Eber Kington.

"However, with Surrey County Council already announcing cuts to the highway budget, youth services and children's centres, this does seem a strange spending priority."

The council's leader David Hodge, said he was not surprised by the criticism, but was confident it will prove to be worth the money.

"This is a modest investment considering the Magna Carta's historic significance and evidence of the economic and cultural benefits resulting from the expected boost in tourism for the area, with the anniversary generating millions of pounds," he said.

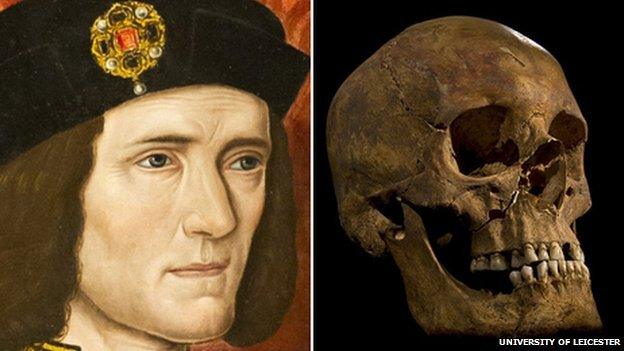

The county council no doubt hopes to replicate the "Richard III effect", which has seen tourists flock to Leicester following the discovery of the king's remains under a council car park.

His reinterment cost more than £3m and a further £4m was spent on a visitor centre next to the car park where his remains were found.

But, the city council argues it was money well spent, as the king has already generated an estimated £60m for the local economy, with £4.5m of that in two weeks' of events surrounding the reinterment.

"The discovery of King Richard lll and his subsequent reinterment has had a greater impact on the city than we could ever have anticipated," said Leicester City Mayor Sir Peter Soulsby.

A £4m visitor centre has been built next to the car park where Richard III's remains were found

The king's reinterment at Leicester Cathedral cost more than £3m

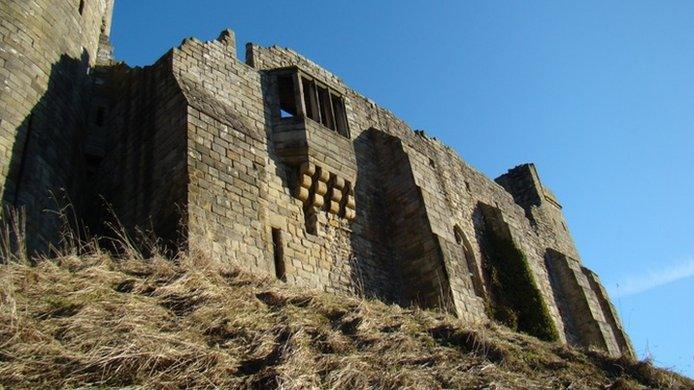

Richard III once owned Barnard Castle, which is located in the County Durham town of the same name, but the town has not been able to benefit from the king's effect.

It is already a popular tourist destination but it has a problem - part of the wall of its namesake castle collapsed in 2009.

Repairs costing between £400,000 and £600,000 are needed - but, six years later the work has still not been done.

Barnard Castle, in the town of the same name, was once home to King Richard III

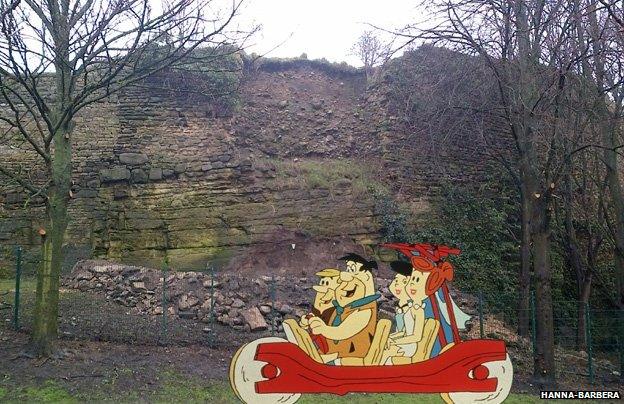

"There were actually tourists calling it 'Barney Rubble' because it looks like a pile of rubble," said Gary Marshall, of the Barnard Castle Walls Trust.

"Now, we've got people saying we've got big mice because we've got a big hole in the wall."

Much of the castle is owned by Lord Barnard and looked after by English Heritage, but the ownership of the part where the wall collapsed is unclear.

Mr Marshall predicts the town "will die" if the repairs are not carried out.

"You are taking away its main tourist attraction," he said.

"What does it say about our town if we are willing to let our castle drop to bits?"

Tourists have called the castle "Barney Rubble", after the Flintstones character

A very different approach was taken with Lincoln Castle, where £22m has been spent improving it in an attempt to attract more visitors.

Much of the money came from the Heritage Lottery Fund, but Lincolnshire County Council spent £4.5m of its own money.

The council, which has been criticised for plans to hand over 30 of its libraries to volunteers in an effort to save £2m, insists spending millions on the castle was justified.

Tourism development manager Mary Powell, predicts a £68m boost to the local economy and the creation of about 1,100 new jobs.

"As many visitors to Lincoln stay in rural Lincolnshire, we would expect these economic benefits to be felt across the county," she said.

Lincoln Castle has been improved at a cost of £22m

Lincoln Castle has a copy of Magna Carta, shown here bottom left, alongside other copies

A vault was built to house Lincoln's copy of Magna Carta as part of the castle renovation, and the council hopes this will further boost tourism for years to come.

"The improvements also mean the castle is in a much better physical condition than it was," said Ms Powell.

"This should reduce the risk of taxpayers having to pick up any hefty repair bills over the coming years."

Apethorpe Hall was bought by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport for £3m

But, investing public money in historic buildings does not always go to plan.

Apethorpe Hall in Northamptonshire, a favourite haunt of King James I, was compulsorily purchased by the government for £3m.

English Heritage planned to spend a further £4m restoring the Grade I listed mansion, then recoup the public's money by selling it.

Unfortunately, the gamble did not pay off.

After spending £8m in repairs - double the amount planned - Apethorpe Hall eventually sold for £2.5m.

English Heritage's chief executive Simon Thurley, welcomed the sale and maintained the project had saved "by far the most important country house to have been threatened with major loss through decay, since the 1950s".

English Heritage's Simon Thurley spoke about plans for Apethorpe Hall in BBC documentary A Very Grand Design

Was it money well spent?

"If you view it as a grant it doesn't look so silly at the end of the process," said Matthew Slocombe, director of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

"It would have been a national tragedy if Apethorpe Hall had slipped into the ground through neglect and dereliction.

"It's difficult of course when there is competition for public funds and I'm sure most people would say if it's a choice between the health service and historic buildings then the health service would win."

James I is said to have cemented his relationship with lover George Villiers, at Apethorpe Hall

But, Mr Slocombe argued investing in heritage often leads to wider economic benefits, not least revenue from tourism.

Apethorpe Hall's new owner has agreed to open the building to the public for 50 days annually, and English Heritage will get to keep the revenue generated from tours.

The new owner, Jean Christophe Iseux, Baron von Pfetten, is also committing his own money to the continued restoration, which requires many more millions of pounds.

"Our vision for Apethorpe is to help this house regain the place in British history that it deserves," said Baron von Pfetten.

For more stories like these find us on Facebook, external.

- Published15 June 2015

- Published17 April 2015

- Published17 April 2015

- Published1 April 2015

- Published1 April 2015

- Published30 March 2015

- Published26 March 2015

- Published31 January 2015

- Published4 November 2014

- Published7 December 2013