Strange beauty: The photographers capturing urban decay

- Published

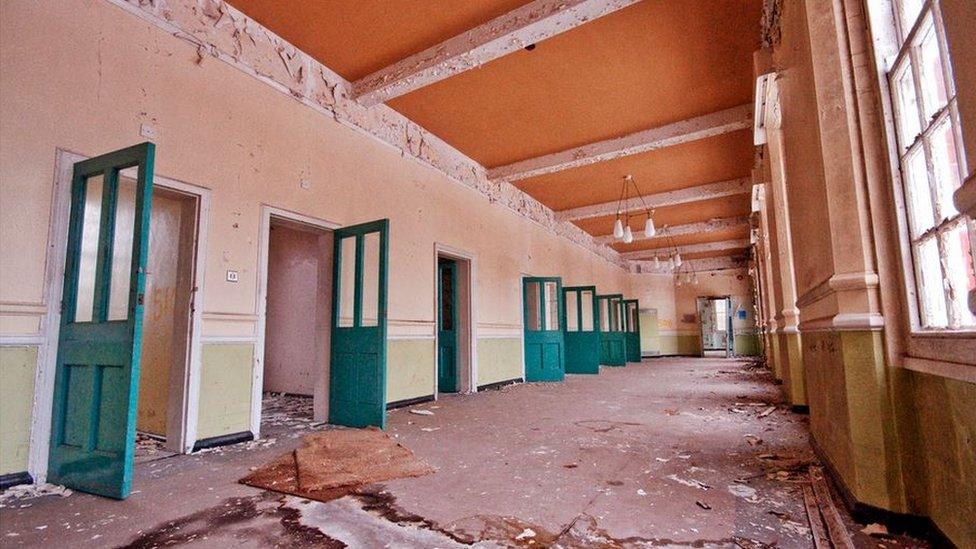

Nature is slowly reclaiming the abandoned Fourth Lancashire County Asylum, near Preston, which closed in 1995

Photographers with an eye for decay are venturing into derelict buildings in the name of "urban exploration". But who are these intrepid hobbyists and why do they put themselves in danger for the sake of a picture?

It takes some imagination to look at a derelict building and see beauty in its broken windows and rotten floorboards.

But for a group of daredevils known as "urban explorers", it's exactly this level of decay that attracts them to the likes of abandoned hospitals, factories and mills.

"Urbexing" is carried out all over the world by those hoping to capture crumbling relics on film before they completely disappear.

Though some members still have their limits - "I'm not up for sewers," quipped one - nowhere is out of bounds.

But what's the appeal in visiting these neglected sites?

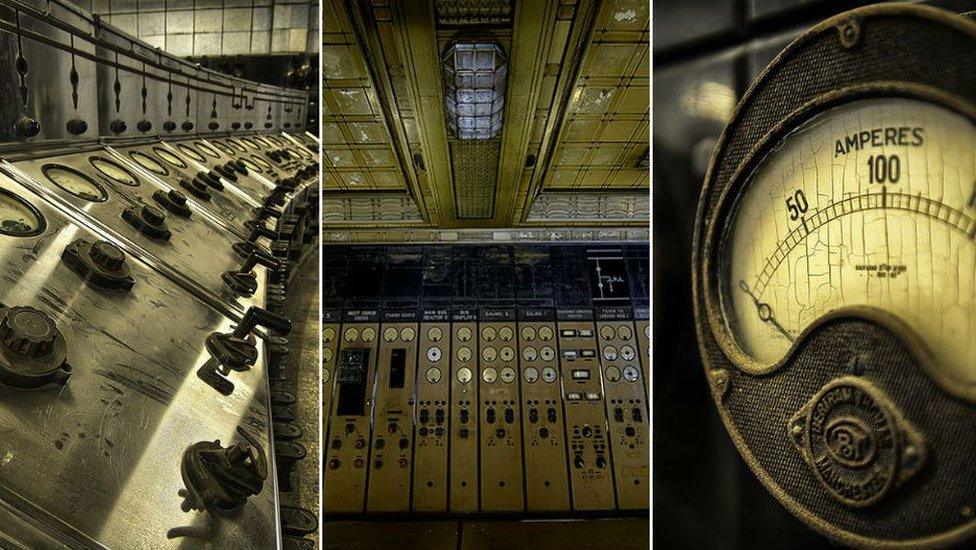

Sheffield's old Post Office building was the city's central site for almost 90 years

"I like the peace and quiet, the sense of history," said one explorer, who asked to be called "Dan".

"Getting into places that are no longer used, you're away from the humdrum of society and can slow down and get a feeling of what's gone before."

Another, known as Urbex South England, described it as a "calling".

"I love to see places that tell a story and are pretty much left as the day they were abandoned and nature has started to take over," they added.

A boat ended up in the disused swimming pool at Crookham Court School in Newbury

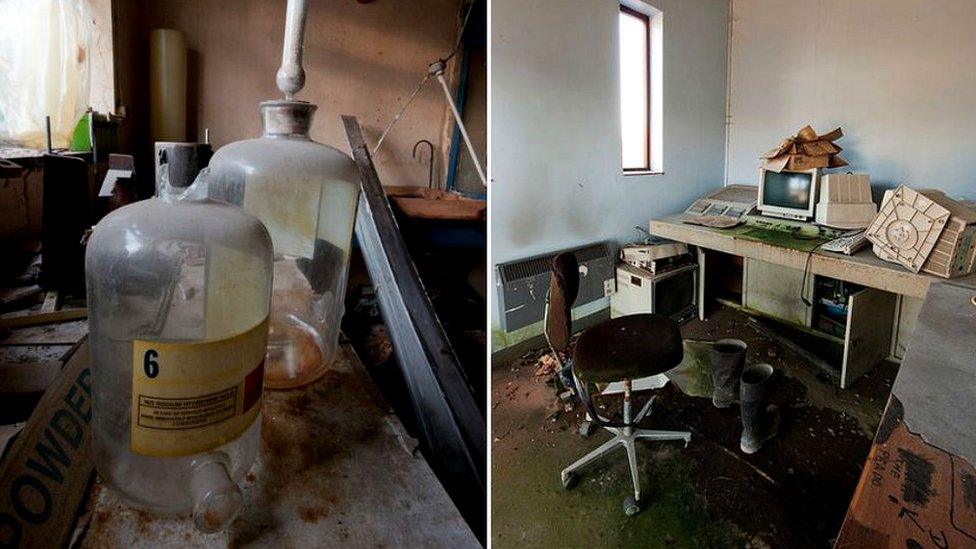

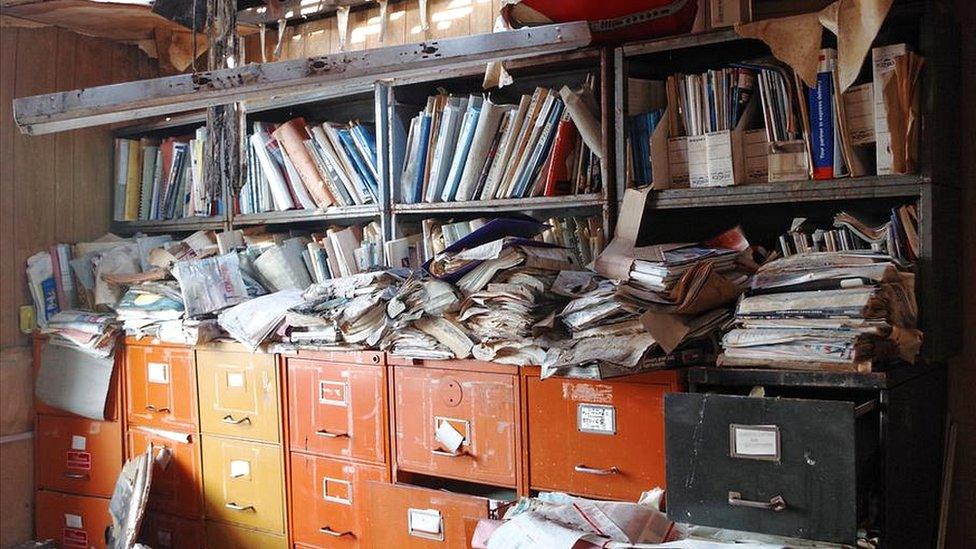

Urbexers aim to capture how things were left, like this office at Lostock Power Station in Northwich, Cheshire

For "Mexico75", it's a lifelong habit which became almost a full-time pastime.

"I've been exploring as long as I can remember. When I was a kid I was always fascinated with abandoned buildings and ruins and took any opportunity to sneak in to places I shouldn't be," he said.

"My family were keen walkers and we'd holiday in places like Wales and Cornwall so while they were taking in the views I'd be disappearing down old mine [shafts] and into ruined engine houses.

"Then a few years ago I stumbled across an internet forum and found that other people had the same sort of interests and that's when it became more of a hobby."

One explorer was lucky enough to take a tour of Battersea Power Station

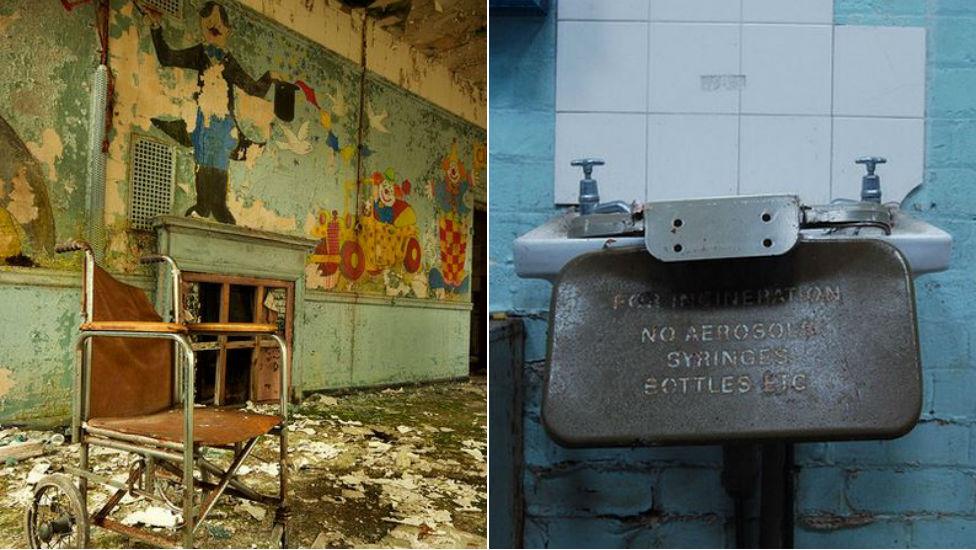

Gateshead Borough Asylum opened in 1914 to care for the "sick and infirm, recent and acute, and epileptic" but closed in the mid-1990s

One of the main draws for explorers is the kudos that comes from posting travelogues and photographic essays about their excursions on internet forums, said Luke Bennett, lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University.

Certainly, it's these kind of accounts which, however unwisely, have inspired others to take part in the activity, by offering a glimpse into a world the average person would never dare chance exploring themselves.

"Chris" became interested in the activity after seeing pictures on one such website of Chernobyl and Prypiat - abandoned cities in Ukraine.

His attitude to going on expeditions is pretty relaxed; he "wanders" into hospitals and "potters" around mills, but the dangers of poking around crumbling buildings are not lost on him.

Rotting floors and staircases are just one of the dangers explorers face, such as this one at Hartington Cheese in Derbyshire

"You have to keep your wits about you and [ask yourself] is that floor totally rotten? if the answer is yes, just don't do it," he said.

"I find it comes down to knowing your limits and not rushing."

"It can be dangerous," warned Dan. "I have fallen through floors twice - once was a ground floor and once on [a flight of] stairs.

"Luckily, I was fine, but it makes you think."

What can make urbexing even more dangerous is when explorers venture into buildings that might still be operational, said Dr Bennett, who specialises in industrial property safety.

The Hickson and Welch chemical plant in Castleford, West Yorkshire, shut its doors a decade ago

Even more concerning, he added, is the effect of trespassing on landowners and security staff.

"There's an under-appreciation of the knock-on effects and ethical complications of going into live systems like subways and operational buildings.

"Security guards work terrible hours for minimum wage and are fearful of organised gangs like metal thieves.

"The last thing they need is people who, as far as they're able to tell, aren't there for calm, aesthetic reasons, but could be there to steal what's left of value."

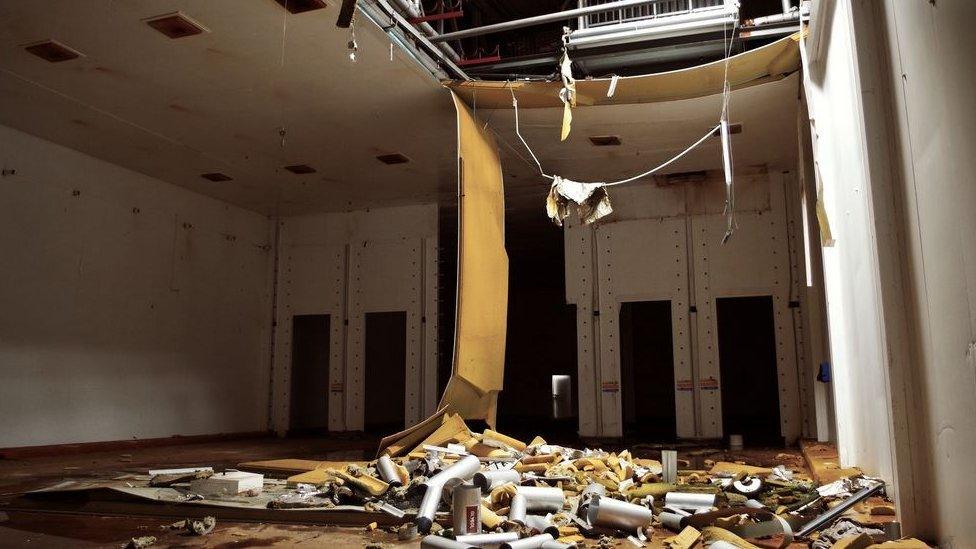

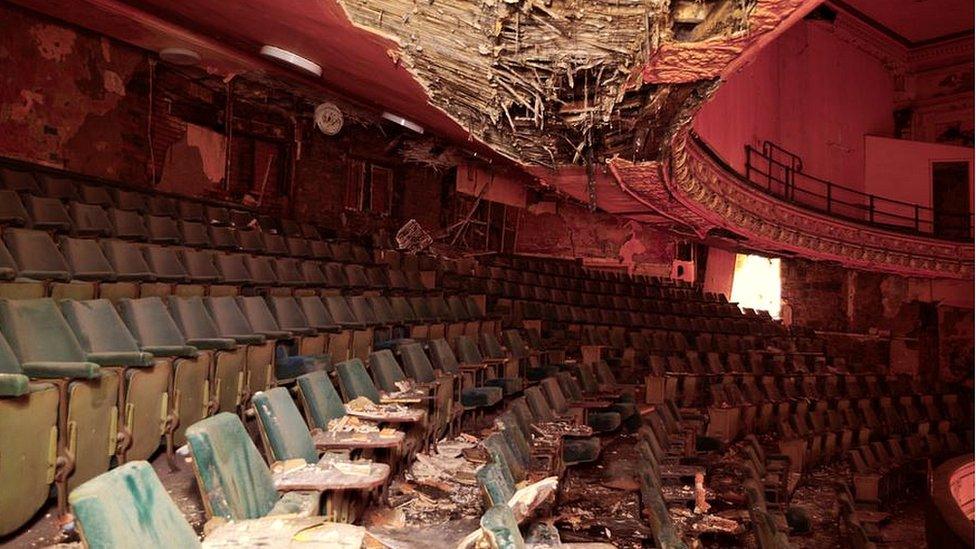

The Burnley Empire Theatre in Lancashire is just one of the many listed buildings urbexers have photographed

One urbexer said he had been caught a number of times by security guards who were "relieved it was only a couple of chaps with cameras".

But while danger and nuisance are relatively minor side-effects of urbexing, each expedition has the potential for far worse consequences in the form of legal repercussions.

While not a criminal offence, trespass on private land constitutes a civil wrong for which offenders can be sued.

Additionally, if someone is caught and convicted of aggravated trespass, they can face up to three months in prison or a fine.

The urbexing philosophy is 'take only photos, leave only footprints'

The majority of explorers are cautious and stick to their philosophy - "take only photos, leave only footprints" - entering only if it is easy to do so and doing nothing to disrupt the site.

"I was a detective constable so I know the law and don't overstep it," said Dan. "No damage is caused and I have no criminal intent [so] I can argue my point if needed.

"Yes it's trespass, but the police don't have time to deal with… civil infringements."

Oldham family business Williamsons, established in 1920, supplied fire and rescue equipment, before closing in 2013

But there is still an attitude among some that any site is "fair game".

"The sites won't explore themselves and it gives a tangible sense of history and heritage in a way that learning through other mediums cannot," said one anonymous explorer.

"But I don't like the view that some explorers have that it's 'only trespass.' Despite not being a criminal offence, it is unlawful."

The rules on trespass

In England, trespass is a civil offence when committed on private land

Landowners can choose to sue trespassers

It becomes if a criminal offence if committed on land owned by the monarch or

It falls under the category of "aggravated trespass"

This is classed as an offence whereby a person obstructs or disrupts the activity being carried out on the land

If convicted, trespassers can face a prison sentence of up to three months or a fine

Source: Crown Prosecution Service/The Sentencing Council

Save Britain's Heritage said while it does not wholly support the activity, photographs taken by urbexers have helped highlight the importance of preservation work.

"The sites targeted are often of historic or architectural significance, and unlawfully entering places them at risk of getting damaged [and] can place considerable strain on the buildings," said caseworker Mike Fox.

"The flipside is [it] can become a useful tool in raising awareness about threatened heritage buildings, bringing their plight to a wider audience, which might otherwise have gone unknown... so their actions are not without value."

West Park Mental Hospital in Epsom, Surrey and St Mary's Lunatic Asylum in Stannington, Northumberland, have both been urbexing sites

Opinion in the urbex community is divided on whether they play a part in creating a lasting legacy.

"I don't think there is an importance to exploring these places. The whole documenting for [the sake of] history bit seems like romanticism," said one.

But for many more it's exactly this sentimentality that drives them to continue entering these often unsafe structures.

"Many sites are simply falling into total and utter disrepair and explorers can capture the last moments before its bulldozed," said Dan.

"I like seeing the often strange beauty which is about to be lost forever."

- Published3 November 2014

- Published11 February 2014

- Published11 February 2014