Italia 90: How the 1990 World Cup changed England

- Published

Last time England reached the last four of the World Cup was at Italia 90 - a tournament which is credited with changing football in England, and even the country itself.

Back in 2015, on the 25th anniversary of the semi-final defeat to West Germany, we explored how that summer of Gazza's tears and Nessun Dorma affected England.

But now, with England once more just one game away from the final, it feels like a good time to look back at it again.

This article was originally published on 4 July 2015.

Football became more middle class

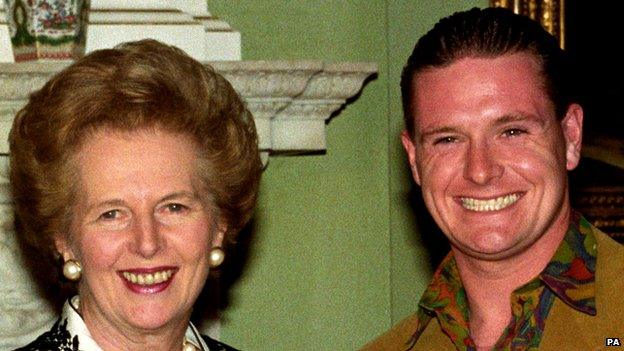

Margaret Thatcher famously disliked football but by October 1990 she was posing for photos with Paul Gascoigne

The 1980s were dark times for English football. Fans were dying in stadiums, hooliganism was rife, clubs were banned from playing in European competitions and attendances had fallen.

Prime minister Margaret Thatcher had wanted to introduce an ID card system that would have meant only registered fans could attend matches. Papers released in 2012 revealed the government briefly considered withdrawing from the 1990 World Cup amid fears the tournament would provide a "natural focus" for hooliganism.

Against that backdrop it would almost have been unthinkable that football would soon become a sport enjoyed by many middle-class people.

But as England's stars progressed through the tournament, an increasingly gripped nation watched on TV, accompanied by Luciano Pavarotti singing Nessun Dorma - the BBC's choice of theme music, external.

Within a few months a play based around the England v West Germany semi-final - An Evening with Gary Lineker - was a stage hit, and was even nominated for an Olivier Award, external.

Reflecting on the 1990 World Cup, Lineker, who scored four of England's goals, said: "It was a seminal moment almost, in terms of football in this country. Lots of different kinds of people got interested in football, all different classes of people, I think it had a significant effect on the growth of football."

There was rioting before the England v Holland game at Italia 90 but the sport became much safer as the 1990s progressed

Prof Matt Taylor, of De Montfort University's International Centre for Sports History and Culture, is keen to stress there had always been middle-class football fans but agrees the game changed.

"The social constituency of football definitely changed in the 1990s but the World Cup was one of a number of factors.

"The 1980s was a really low point, people forget how much of a cultural outpost football had become. In newspapers, it was very much restricted to the back pages and it represented much of what was bad about 1980s society.

"It was a period when there were a lot of disasters and it made people question whether the country could organise public events.

"So Italia 90 came at an opportune moment for change, along with the Taylor Report, external, which was quite a radical report and said football clubs had to treat their fan base as customers.

"It was one of a number of things that helped to position football at the forefront of English cultural life. It could have happened just for the month the tournament was on but it struck a chord. Football, amazingly, was seen as being cool and that wasn't likely to happen five or six years prior to that."

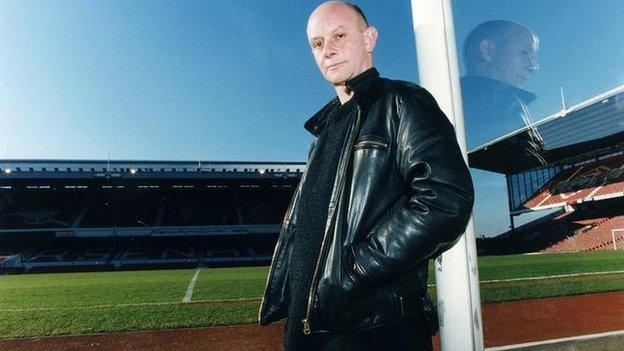

Gary Lineker, who scored England's semi-final goal, says different classes of people became interested in football through Italia 90

In the 1990s football filtered into much of England's cultural life, from Nick Hornby's book Fever Pitch, to Sky buying up the rights to Premier League games and satellite dishes appearing on houses up and down the country. Cambridge-educated comedian David Baddiel teamed up with fellow football fan Frank Skinner to host Fantasy Football League, a BBC football comedy show based loosely around a game that captivated broadsheet newspaper readers, and is still going strong online.

Baddiel and Skinner's anthem Three Lions reached number one in both 1996, external and 1998, external while Gazza had a hit with Fog on the Tyne, external.

Prof Taylor says it was "thin pickings" for football in the arts before 1990 but then "it became a topic that could be considered of interest beyond just football fans".

Music journalist Colin Irwin said: "Italia 90 was when they had Nessun Dorma and I think that changed things. People started calling it 'the beautiful game' and opera was associated with it. People began to think of football as an art form.

"It had been damaged by that horrible period of hooliganism, racism and horrible football but then you had opera, Paul Gascoigne and Gary Lineker, and women started taking an interest. Stadiums became much safer and the whole culture of football changed really."

Nick Hornby said the success of Pete Davies's book All Played Out, about England's World Cup campaign, made it easier for him to get Fever Pitch published

Not everyone welcomed the changes. The cost of attending matches rose significantly in the 1990s and led to accusations that traditional working-class fans had been priced out of the game.

"What happened with Italia 90 is that football became reimagined as a people's game again and these people were from a broader base than before," says Prof Taylor. "But there is a problem if the social base that had propped up football for so long is edged out.

"The pricing out of the working classes has happened and I think it's a concern for the future of football, as is the low number of young fans."

Attitudes to crying changed

Probably the most famous image of the 1990 World Cup is that of England's star midfielder Paul Gascoigne in tears. Gazza was booked in the semi-final, meaning he would miss the final if England got there.

Gascoigne realised immediately what had happened and began to cry as the game went on around him. Gary Lineker was famously caught on camera turning to the England bench urging manager Bobby Robson to "have a word".

There was no stiff upper lip from the 23-year-old midfielder, instead Gascoigne just displayed the raw emotion of terrible, devastating disappointment.

Speaking to the BBC in 2010, external, Gascoigne said: "Once I knew I was going to miss the final you could see how heartbroken I was and I just could not stop the tears."

Margaret Thatcher cried as she left Downing Street for the last time after resigning as prime minister in November 1990

Dr Thomas Dixon, an expert on crying and the author of Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears, said Gazza was far from the first footballer to cry - but his tears were different.

"Normally sportsmen wept because they had just won something or lost something, or perhaps because they were at the end of their career," says Dr Dixon.

"With Gazza it was self-pitying, out of control and in the middle of a match that he should have been trying to win. The thing that was notable was he was running up and down the pitch in tears."

But even if Gascoigne was not the first footballer to be seen in tears, Dr Dixon still believes he changed attitudes.

"It was a very high-profile example of what was by then seen as the culture of the 'new man' who shows his feelings.

"But he was someone who was a traditional man - a 'lad', heavy drinking - and it was an example of that meeting the 'new man' culture."

There were more tears after England's women lost in their World Cup semi-final this week

Dr Dixon said 1970s sportsmen who cried had prompted letters to newspapers saying they should have shown a stiff upper lip, countered by the likes of agony aunt Marje Proops saying other men should follow their example. And by the time of Gazza's tears the attitude of acceptance was far more common.

And he said Mrs Thatcher's tears when she left Downing Street a few months later helped establish the 1990s as an emotional decade, an image cemented with the outpouring of grief after the death of Princess Diana in 1997.

But even now not everyone approves of blubbing in public. When Andy Murray cried after losing the Wimbledon final in 2012, columnist Toby Young referred to it as a "big girl's blouse routine", external.

Andy Murray was criticised when he cried after losing the Wimbledon final in 2012 - but Dr Thomas Dixon says the criticism comes from "dinosaurs"

Football songs became cool - for a while

New Order brought genuine credibility to England's official World Cup song

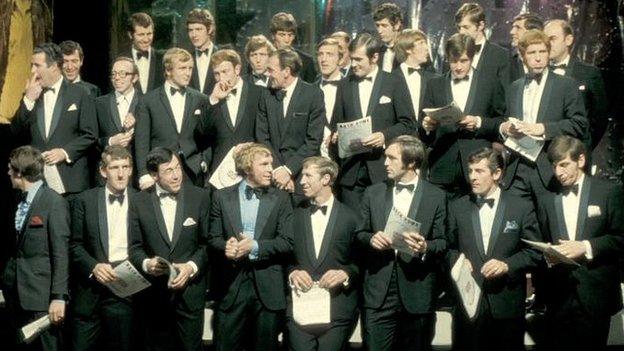

Before 1990, football team songs tended to mean one thing - players standing in a group singing in various levels of uneasiness. Maybe not that tuneful and often dressed in casual knitwear - or even dinner suits.

They were not unpopular. England had reached number one in 1970 with Back Home, external and number two in 1982 with the over-ambitiously-titled This Time (We'll Get It Right), external.

But they were not songs with a lot of credibility. Until 1990 when the FA took everyone by surprise by collaborating with New Order, one of the most critically acclaimed and influential bands of the previous decade.

World In Motion, external was recorded under the band name EnglandNewOrder but was in reality a New Order song with a handful of the England team joining in on the chorus - and a John Barnes rap. It became New Order's only number one single and topped the charts for two weeks.

The England 1970 World Cup squad sang Back Home on Top of the Pops clad in dinner suits

Colin Irwin, who was editor of Number One magazine at the time, said: "Because it was a band of real credibility, at the time it was extraordinary. People wondered what New Order were doing, they thought they had gone mad.

"Before then it had been all these cheesy songs with self-conscious footballers giggling.

"World In Motion was not especially a football song. It had footballing connotations but they could be applied to life in general. It had the line in it 'express yourself' - meaning show your talent - but you could interpret it in other ways. It was quite clever that they didn't go totally committed to a football song, an anthem.

"It was a very clever piece of music, and people do regard it as the best football song."

In 1996, when England hosted the European Championships, Baddiel and Skinner joined forces with the Lightning Seeds to record Three Lions - an England team song with no footballers on it.

Irwin, whose book Sing When You're Winning examines the history of terrace chants, said: "Three Lions was brilliant also, because of the video and the sentiments expressed by all football fans - 30 years of hurt. It just caught the imagination of people so well, and it's very good lyrically. It was clearly written by football enthusiasts."

But not all football songs were so well-received. The official tournament song of Euro 96 was by Mick Hucknall, external - "truly awful" is Irwin's verdict - and the Spice Girls and Echo and the Bunnymen, external combined for the England 1998 World Cup song but failed to delight the fans, external as EnglandNewOrder had.

And no football songs have reached the heights of World In Motion and Three Lions since.

"Maybe people thought this is an easy way to get a hit song but it doesn't necessarily work," says Irwin.

"It's some undefinable magic and you need to be a committed football enthusiast to get it."

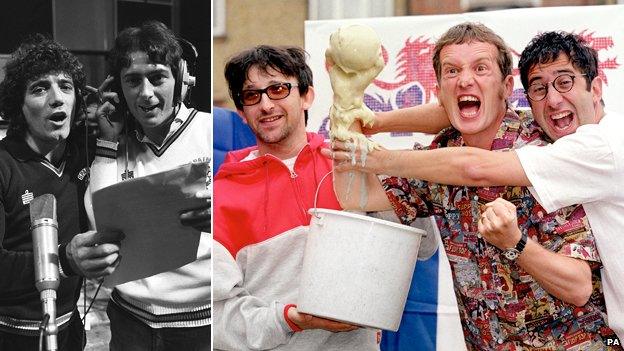

In the space of a decade-and-a-half England songs went from Kevin Keegan and Trevor Francis in knitwear to Baddiel and Skinner and the Lightning Seeds

Penalties became something to terrify the English

Penalty kicks were invented in 1891. For the first 99 years of their existence they provided English football with many moments of tension but were essentially just part of the game. On 4 July 1990 all that changed.

When the semi-final finished in a 1-1 draw, England found themselves in their first penalty shoot-out. West Germany by contrast were old hands, having won shoot-outs in both the 1982 and 1986 World Cups.

The Germans dispatched all of their penalties while Stuart Pearce had his saved and Chris Waddle blazed the final spot-kick over the bar to seal England's fate. Two of the country's best players were left almost as inconsolable as Gascoigne.

Peter Shilton did not manage to save any of West Germany's penalties

Although both cashed in on their notoriety with a Pizza Hut advert, the misses affected them both - Waddle chose not to take a penalty when his Marseille side lost a shoot-out in the European Cup final a year later, while Pearce famously erupted with relief and emotion when he scored in England's only shoot-out win - against Spain at Euro 96.

England have now been knocked out of six major tournaments on penalties, with some of the top players in the world among those to have missed - David Beckham, Frank Lampard and Steven Gerrard, for example - and the very mention of a penalty shoot-out leads to assumptions of defeat, failure and panic.

Prof Matt Taylor said: "It's a narrative that returns every time and I think people like it in a way. 'Why can't we be as good as the Germans?' is just part of the story now.

"After Italia 90 the penalty shoot-out became another thing we could use to describe our country and its weaknesses whereas other countries see it as a chance to show their strengths."

Stuart Pearce exorcised his demons by scoring in a shoot-out win in 1996 but ended the tournament comforting another team-mate who had missed

- Attribution

- Published8 June 2015

- Attribution

- Published2 July 2015

- Attribution

- Published26 June 2015

- Attribution

- Published4 December 2013

- Attribution

- Published7 June 2014

- Published28 September 2012