Sheep rustlers and bank robbers: The changing face of crime

- Published

The image of poachers as harmless folk killing animals to feed their families is very outdated and unrealistic, say police

As long as laws have been in place, people have been breaking them. But how has the face of crime changed over time? Following the conviction of two men for sheep rustling, BBC News takes a look at some seemingly old-fashioned crimes.

Sheep rustling

Some 90 sheep worth £35,000 were taken from farms in Lancashire and Yorkshire

Sheep rustling is one of the oldest recorded crimes and though it sounds like it belongs in the pages of history, it still goes on.

Andrew Piner and Thomas Redfern were both convicted of the crime and will be sentenced in November.

The pair stole almost 90 sheep worth £35,000 from farms in Lancashire and Yorkshire.

The theft of sheep is a major problem for farmers, said Julia Mulligan, the Police and Crime Commissioner for North Yorkshire, who is taking a national lead on tackling the problem.

"With sheep rustling it's about money: sheep are valuable commodities and if something has a value then it will be targeted by thieves."

But the financial cost of losing their livestock is not the only damage caused to farmers.

"Farmers breed bloodlines," said Ms Mulligan.

"They can spend generations nurturing those bloodlines so when the results of that work are stolen it's not just about the financial value of the sheep, although that too can be considerable."

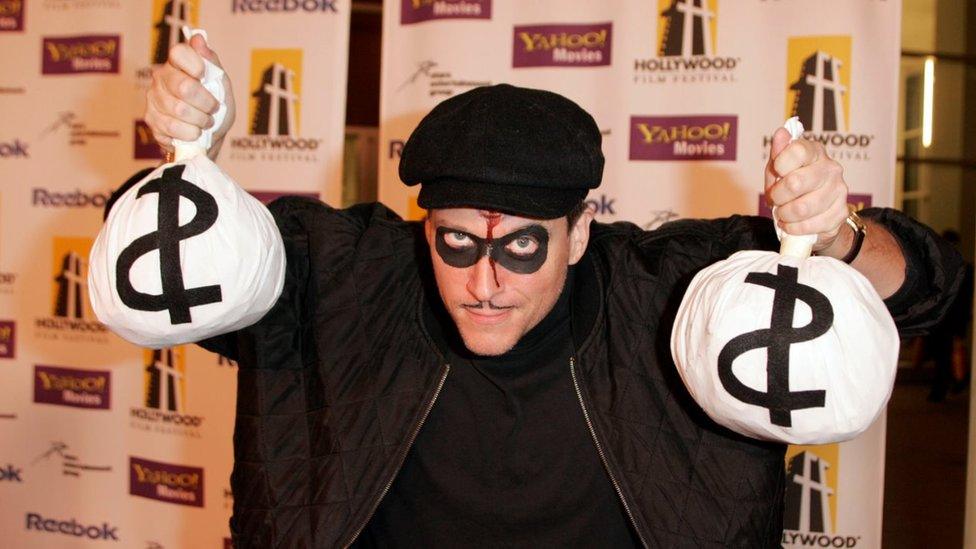

The bank job

The traditional bank job is becoming increasingly rare

The mention of a bank robbery conjures up an image of shotgun-wielding masked men filling swag bags with cash.

Though that was perhaps never the most accurate depiction of the crime, the bank job is now becoming much rarer.

There were 118 bank robberies in 2014 compared with 847 in 1992, according to the British Bankers Association (BBA).

Better security systems coupled with less money to be gained have contributed to the drop, the BBA said.

Disorientating fog, a DNA spray almost impossible to wash off, fast-acting screens and improved CCTV are all weapons employed by banks against robbers.

And the risks and returns do not add up, according to economists Barry Reilly, Neil Rickman and Robert Witt.

In 2012 the trio analysed the statistics, external of bank robberies.

They concluded the average yield from a bank job was just over £12,000 per gang member.

"The return on an average bank robbery is, frankly, rubbish," they said, adding: "It is not unimaginable wealth."

There are also fewer branches for criminals to target - 9,700 in 2014 compared with more than 17,000 in 1990, according to figures, external from the Campaign for Community Banking Services.

Poaching

Poachers particularly target deer in the run up to Christmas

Poaching seems like it belongs to an age of princes and paupers; killing the local lord's animals was a crime otherwise law-abiding men committed to feed their starving families.

But poachers today are a far cry from the quaint countryside criminals they have been portrayed as in the past.

"Modern poachers are no longer peasants bagging animals for food," said Insp Ashley Farrington of Staffordshire Police.

"As well as those who kill for the meat market, there are quite a number who kill purely for sadistic sport.

"This type of poacher is more likely to use powerful dogs bred especially to bring down a deer rather than going for a clean kill with a gun."

So why do these crimes, which historically seemed to be motivated by desperation, still exist?

"Poaching today can be done for financial gain but also simply as a recreation for criminals," said Ms Mulligan.

"The idea that they are committed by people who need food to survive is a long way from the reality - these people are criminals."

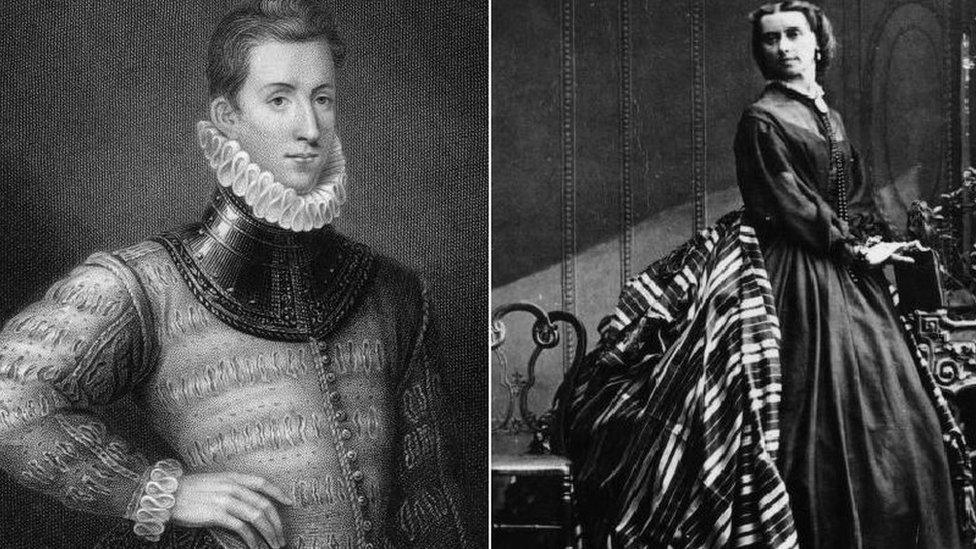

Fashion crimes

Men in the Elizabethan age were targeted by thieves after starting to wear their purses on their belts, as were woman in Victorian England who hid their purses in their bustles

Some crimes depend on the current fashions.

In the Elizabethan and Jacobean period, men wore purses on their belts, and so a new breed of thief known as the purse-cutter followed.

Women in the Victorian age would keep their purses in their bustles - the frames below their dresses - and again a new kind of criminal began to target them.

The Artful Dodger and co targeted gentlemen's handkerchiefs because there was a big market in the fashionable accessories.

Another crime - van dragging - has also been made practically impossible as technology has advanced.

The felon would climb on to the back of a horse-drawn goods wagon and throw its contents out to accomplices.

"You could still do that on a slow-moving vehicle even if it was powered by an internal combustion engine for a while, but you trying doing that on a lorry travelling fast today," said Prof Emsley.

- Published1 October 2015

- Published6 June 2013