Protecting England's historic herds

- Published

Dartmoor ponies are to be painted with a blue line which will make them more visible at night

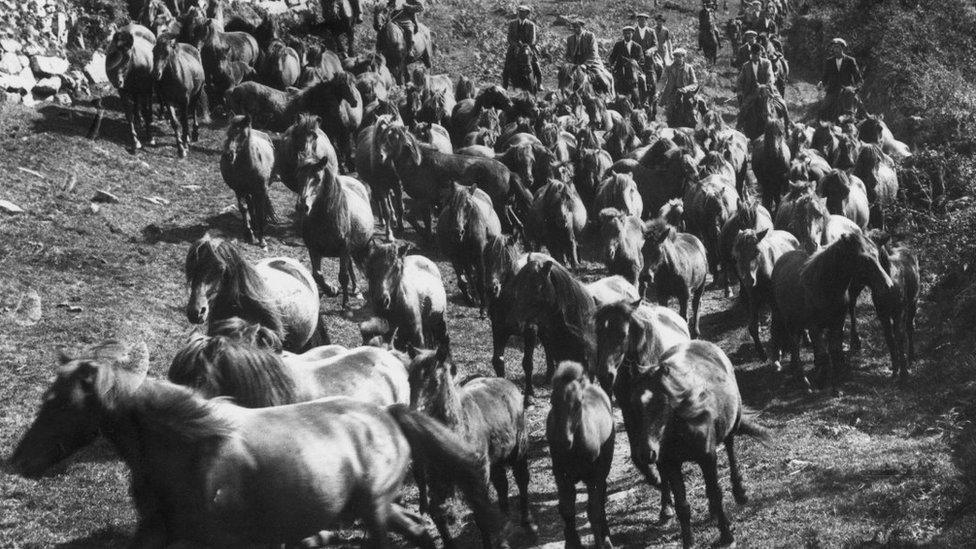

Dartmoor ponies are to be painted with fluorescent paint in an attempt to reduce the number being killed by cars at night. But they are not the only historic herds that need protecting. So what is being done to help animals exposed to the dangers of the modern day?

Dartmoor Ponies

Ponies have been ambling around Dartmoor in Devon for more than 3,500 years.

But though they are hardy animals capable of withstanding harsh winters they are also at risk.

About 60 have been killed by cars so far this year, prompting the Dartmoor Livestock Protection Society to follow the example of the Finns and paint its livestock with reflective paint.

Just as deer antlers are daubed to make them show up in headlights, the ponies should now give off an "alien glow" to alert drivers to their presence.

Karla McKechnie, livestock protection officer for Dartmoor Livestock Protection Society, said it was "early days, but the trial was going well".

"Motorists will not be able to tell it's an animal, they'll just see this alien glow, which might be able to reduce the speed of these motorists," she explained.

Though they effectively fend for themselves, the ponies on Dartmoor are not truly wild animals - they are all owned by farmers who let them graze on the commons.

Numbers have dropped from about 30,000 in 1950 to about 1,500 now.

Chillingham Cattle

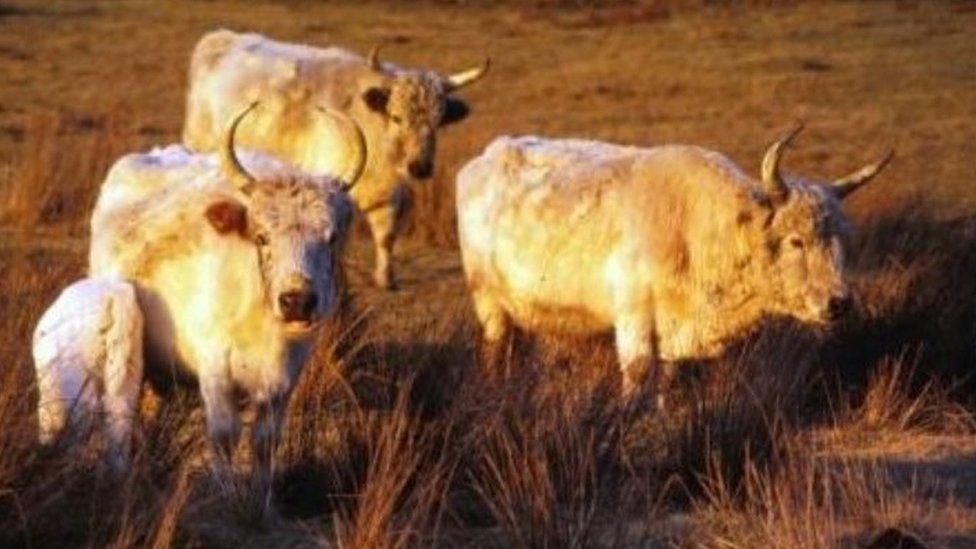

The cattle at Chillingham Castle in Northumberland can be said to be truly wild - the association that looks after the animals claims they have never been treated by a vet nor even touched by human hand.

They fend for themselves in the castle grounds and, as no outside animal has been introduced to the herd for more than 300 years, the cattle themselves and Mother Nature are responsible for their population levels.

Each animal in the herd is genetically identical and they are regarded as a scientific curiosity as they seem to suffer no ill-effects through in-breeding.

There are currently about 100 members of the herd, almost half of whom are bulls but the numbers have fluctuated wildly over the years. There were just eight cows and five bulls in 1947 after a particularly harsh winter.

The bulls fight each other throughout the year for breeding rights.

The cows can live to be 15 and start having calves at the age of three and on average, about half as many calves are born each year as there are adult females in the herd.

Warden Ellie Crossley said there was a current group of younger males nicknamed the Hoodies as "they have forgotten their manners and have little respect for their elders".

The biggest threat to the cattle, other than the weather or in-fighting, arrived in 2001 with the Foot and Mouth disease.

It was recorded just six miles (10km) away and the cattle were closely monitored throughout the period.

New Forest Ponies

Like their equine cousins in Devon, the 5,000 New Forest Ponies are not actually wild.

They are all owned by commoners, a group of about 700 people who exercise their right to let their animals graze on the forest land.

The right to graze ponies in the New Forest dates from 1079 when the forest was created by the court of King William I.

In exchange for sticking to the strict forest laws, commoners were allowed to graze their livestock on the king's lands.

And also like their Devon counterparts, the biggest threat the New Forest ponies face is from traffic, with dozens dying on the roads each year.

Measures have been taken in a bid to reduce the risk.

A 40mph speed limit was introduced in 1990, speed ramps have been installed and roads narrowed - but deaths persist.

For the past few years ponies have been fitted with reflective collars to illuminate them at night, the time when they are most at risk of being struck.

And the indications are it is working, said head agister, external Jonathan Gerrelli.

"It is very difficult to prove that an animal has not been hit because it is wearing a collar but we would say the signs suggest it is a success.

"The number of ponies is going up and the amount of traffic is increasing all the time but the accident rate has levelled off and this year is actually lower than previously."

How to be a commoner?

-

Rights Commoners must own land which has historic forest rights. Thousands will have the rights but only 700 exercise them

-

Brand Each commoner must have their own brand with which each of their animals is marked

-

Fees Commoners must pay a fee to the Verderers (who conserve the forest and animals) for each animal

One other threat to the ponies is poisoning from eating green acorns.

Each autumn the commoners release about 300 pigs, which can happily stomach the acorns, to eat them up before the ponies do.

Other hazards to the ponies' health include people dropping litter and dumping lawn cuttings which ferment and can poison the animals.

Richmond Deer

Deer have been wandering around Richmond Park in south-west London for almost 500 years.

There are 630 red and fallow deer roaming freely with the numbers carefully controlled through culls by the Royal Parks.

And the animals play a key role in shaping the parks, their grazing helps preserve the park's grasslands while they also eat seeds stopping trees and plants from growing in unwanted areas.

Though they are managed, the animals are wild and visitors to the park are warned to stay at least 50m (165ft) away from the deer.

They are especially dangerous during the rutting season in autumn when stags and bucks will fight for the right to breed with the finest hinds.

And mothers can be extremely protective of their young who are normally born between May and July each year.

One of the biggest threats to the deer are dogs.

In 2012, for example, three deer were killed by dogs while two dogs were injured and a third killed by defensive deer.

In 2011 the park's deer were filmed fleeing from a Labrador called Fenton, with the original video being seen by more than 13 million people, external and prompting numerous parodies.

Visitors are not allowed to collect the park's conkers as they are a valuable food source for the deer.

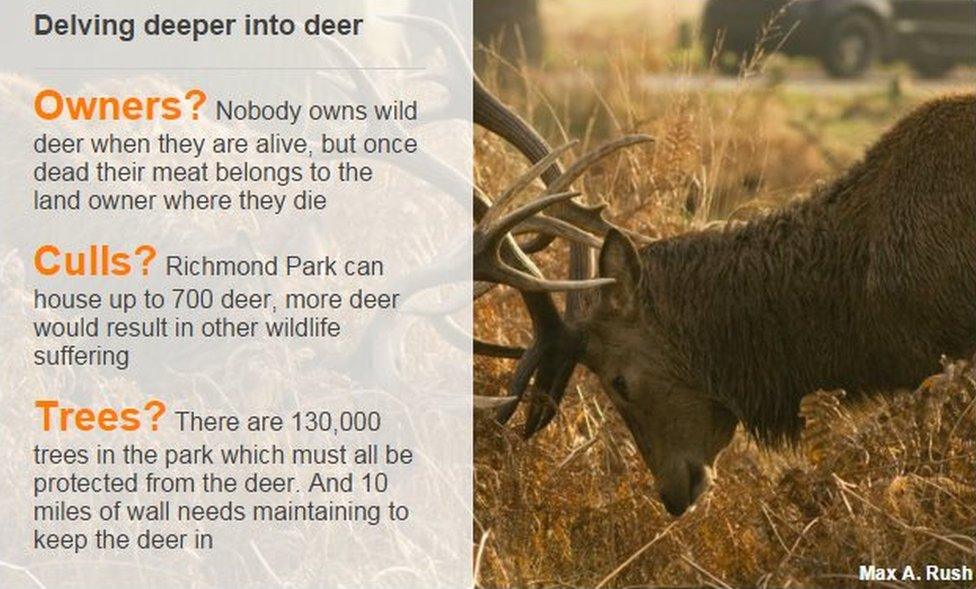

Delving deeper into deer

-

Owners? Nobody owns wild deer when they are alive, but once dead their meat belongs to the land owner where they die

-

Culls? Richmond Park can house up to 700 deer, more deer would result in other wildlife suffering

-

Trees? There are 130,000 trees in the park which must all be protected from the deer. And 10 miles of wall needs maintaining to keep the deer in

The speed limit on the park's roads was reduced from 30mph to 20mph in the 1990s, a move that saw the numbers of deer being killed by cars drop from more than 20 a year to one or two at worst. The road is also closed to vehicles at night.

Adam Curtis, deputy superintendant at Richmond Park, said deer have died after eating litter.

"The deer are a major attraction for people and the vast majority of visitors respect that they are wild animals who need to live in a natural way."

Seal Sands Seals

Among the sea of man-made industrial structures found on Teesside there is a sanctuary for nature.

Sandwiched between Hartlepool and Middlesbrough, Teesmouth National Nature Reserve is a 350-hectare (865-acre) haven for wildlife.

Fences and well-maintained paths keep humans from getting too close to the habitats and the animals are largely left to fend for themselves.

And the most famous residents, in an area appropriately named Seal Sands, are the common and grey seals.

Though they may be treasured now the seals have not always found favour with their human neighbours.

By 1860 the colony had been eradicated, the animals killed off by both pollution and hunters.

But following extensive clean up campaigns the reserve started to flourish and by the 1980s the seals had returned.

Now more than 100 seals live on the sands and it is the only regular breeding colony of common seals on England's north east coast.

More than 20,000 waterbirds also visit the Tees Estuary each year and in 1966 the reserve was designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Tower of London Ravens

Unlike the animals in this article that require preservation, the ravens of the Tower of London are the ones providing the protection.

Tradition dictates that should the six ravens ever leave the castle on the north bank of the River Thames, the fort's White Tower would crumble and disaster would strike England.

The birds were given protected status by King Charles II and have their own personal keeper known as the raven master.

The royal astronomer John Flamsteed had complained the hundreds of ravens living at the castle at the time were interfering with his work.

Rather than risk removing the birds, the king instead decided to move the observatory to Greenwich.

There are currently nine ravens living at the tower - the required six plus three spares.

The birds are all bred in captivity and have their feathers trimmed to prevent them from flying too far from their patrol route.

Some have still managed to escape in the past, however, while others have even been sacked.

According to Historic Royal Palaces, Raven George was dismissed for eating television aerials while Raven Grog was last seen outside an East End pub called the Rose and Punch Bowl in 1981.

Ravens in the wild can live to the age of 15 but the oldest known Tower of London Raven, a bird known as Jim Crow, was 44 when he died.

The ravens eat 6oz (170g) of raw meat a day, plus bird biscuits soaked in blood, and once a week they are given an egg.

They even have their own graveyard in the south moat.

- Published2 October 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published11 November 2013

- Published14 July 2013

- Published3 June 2013

- Published26 December 2012