The police 'super-recognisers' putting names to faces

- Published

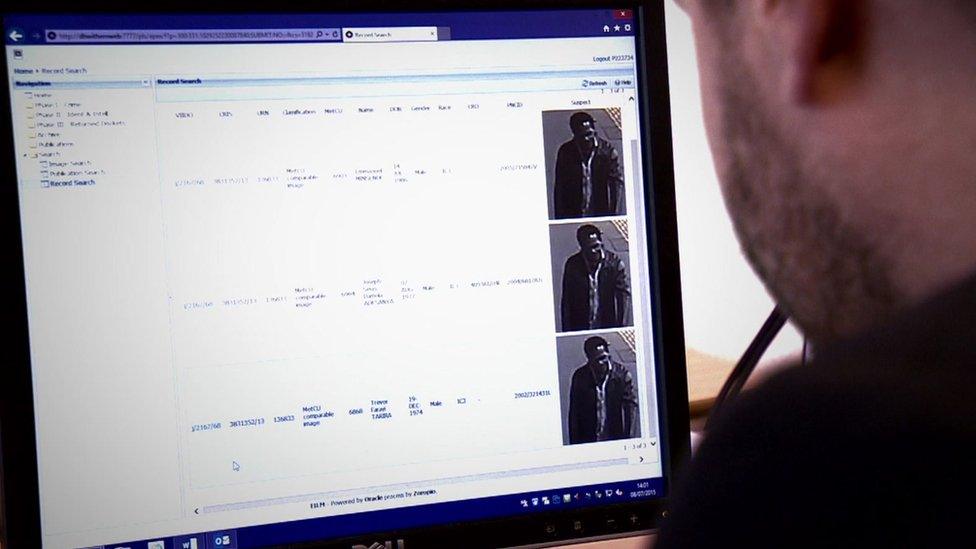

Super-recognisers study thousands of hours of CCTV, scanning the faces of people in crowds

Police officers with the ability to remember the faces of almost everyone they have ever seen are helping to crack down on crime. Meet the "super-recognisers", whose unusual abilities are being deployed in a bid to keep the streets of London safe.

They are the people who quite literally never forget a face, in possession of an extraordinary ability to recognise men, women and children they barely know.

When put to the test "super-recognisers", as they are known in the Metropolitan Police, can recall up to 95% of the faces seen compared to the average person, who remembers just 20%.

For this reason New Scotland Yard deploys an elite team of 140 officers across London to try to capture the most wanted criminals.

The specialist team can recognise people from images just by seeing one or two features

PC Gary Collins is the Met's top super-recogniser and has identified more than 800 suspects from photographs, CCTV and his time policing the streets.

His beat is Hackney, one of the capital's worst areas for crime.

"Whenever an incident happens they'll call me in and show me the footage straight away.

"I'll look [at it] and say, 'Yeah I know that person, I know him from this area or I stopped him on this occasion,' and it's just putting a name to the face."

Super-recognition is seen as one of the Met's most powerful tools

Their talent is thought to be a gift of nature, giving them the tools to identify someone they may have only once fleetingly glimpsed.

Even more impressive is they do not need to see the whole face to make a positive identification.

Could you be a super-recogniser? Take the test, external

"Quite a lot of people I have identified just from their various facial parts, some by their eyes, one guy I've identified by his nose," said PC Collins.

"He had a scarf [covering] the bottom half of his face [and] a hood covering the top half, which was hanging over his eyes.

"He pleaded guilty in court, he said yes, that's me in the footage. [We] got it right, which was quite pleasing."

The features of people in crowds are quickly scanned by super-recognisers looking for criminals

Dr Josh Davis, a forensic facial identification expert from the University of Greenwich, is conducting a study into super-recognisers and their abilities.

He spoke to BBC Inside Out London about his research after putting officers to the test.

"We have tested them on passport images taken 10 years [ago] and they are still able to recognise where they've seen faces before," he said.

"We think super-recognition is nature, rather than nurture, but I can't say 100%. People tend to emerge in their 20s and 30s, we're not really finding any super-recognisers in their teens so far."

Incredible as the skills of a super-recogniser are on the face of it, there are limitations. Research shows they struggle to identify people outside their own race.

Super-recognisers could recall 95% of the faces they saw when tested by Dr Josh Davis

Det Ch Insp Mick Neville, head of the Met's central forensic image team, said: "There is clear, quite politically incorrect scientific evidence that certain people do see their own race better.

"So the best person to identify a Chinese person, is somebody who's Chinese; the best person to identify a black person is a black person."

Though the "cross-race effect," as it is known, is not entirely clear-cut, said Dr Davis.

"There are definitely some white officers in the super-recognition team working in communities that have a large ethnic minority, who pretty much only identify people from that ethnic minority," he added.

The Met believes facial recognition will soon be as crucial as fingerprints and DNA

Mr Neville wants to more than triple the number of super-recognisers in his team and said there should be 500 working for the Met.

He believes facial recognition will soon be as crucial as fingerprints and DNA in creating a mosaic of a suspect's crime history. His team employs a technique called "face net", where super-recognisers identify the same person committing several offences, for which they can be charged and face heavier penalties.

"In the past you would've just been convicted for the one crime [based] on CCTV and probably get a suspended sentence.

"But if the judge sees 10 or more offences, people go to prison," he added.

Super-recognisers helped identify people involved in the London riots in August 2011

To date, the biggest test for the Met's super recognisers has been the summer riots in 2011.

PC Collins was able to identify heavily disguised rioter Stephen Prince, who was seen throwing petrol bombs at police officers.

As a result of his powers of recognition, Prince was caught, convicted and sent to prison.

"It was a good result," said PC Collins.

Super-recognisers were also instrumental in locating murdered teenager Alice Gross last year.

They viewed thousands of hours of grainy, low-quality CCTV and within days identified the schoolgirl and at-that-point unidentified suspect Arnis Zalkalns, allowing them to draw a timeline which eventually led the discovery of the schoolgirl's body in the River Brent.

More recently, super-recognisers helped make more than 200 arrests at the annual Notting Hill carnival, using their skills to scan the crowds for wanted criminals and troublemakers.

With successes such as these, it is clear why super-recognition is increasingly being seen as one of the most vital tools in the Met's fight against crime.

Man or machine?

Can computers outperform people?

Super-recognisers are not the only tool open to the authorities when chasing a face.

The ever-expanding field of facial recognition software offers the mechanical alternative to human talent, the science against the art.

But which offers the best chance of catching the criminal, now and in the future?

The technology presents extraordinarily diverse options, from unlocking phones to feeding the right cat, but it is in the area of law-enforcement it provokes the strongest reactions.

Trialled by authorities across the globe, in the UK it is being put through its paces by Leicestershire Police, who recently defended its use at the Download music festival, saying it was an "efficient and effective" way of tracking known offenders.

While the principle is simple, taking measurements of prominent features and comparing it with a database of photos, the practice is fiendishly complex.

CCTV cannot always provide the best pictures

Prof Raouf Hamzaoui from the Faculty of Technology at De Montfort University, said: "In ideal conditions, computers can outperform people, going through millions of possibilities in seconds.

"But with low quality pictures, typical of CCTV, where there is darkness, facial coverings, blurring and so on, the software struggles and the human does better.

"And this is with average people, rather than super-recognisers."

On top of this concerns about computer processing power, the reliability of databases and ever-present fears over civil liberties, external, have dogged the concept.

However, as with much technology, the potential of the system is only starting to be realised.

Prof Hamzaoui said: "The algorithms will be refined but for the time being, it looks like the human element will continue to win - after all it took millions of years of evolution to develop.

"The key is to match the right tool with the right situation."

Watch BBC Inside Out London on Monday 19 October.