What happens to lone child migrants?

- Published

The government has pledged to take in 20,000 Syrian refugees by 2020

A former soldier caught trying to smuggle an Afghan child into the UK has been given a suspended fine by a court in France. The four-year-old girl is just one of many migrant children who have attempted to, or been coerced into, crossing into the UK, and the number arriving is on the rise. But what happens to them once they reach these shores? And can the system cope?

"My aunty told me: 'Don't ask anything. These people will take you through.' So I didn't ask anything. I just followed.'

In 2011, 16-year-old Makdes was given instructions by her aunt to follow so-called "agents" - or people smugglers - who would help her flee Eritrea, in east Africa, for the UK.

This same aunt had already bailed her out of prison, where she had been jailed along with her father for opposing the current government.

Makdes eventually ended up at Calais's so-called "jungle" - the refugee camp on the edge of the French port where thousands of migrants live. Once in Calais she was handed over to another smuggler who arranged for her to be transported to England in the back of a lorry.

Makdes' journey to the UK is just one of many made by lone migrant children, and the number arriving is on the increase.

The latest Home Office figures suggest there were 2,654 asylum applications in the UK, external for lone migrant children in the year ending September 2015 - an increase of 50% on the year before.

"I'd never seen these kind of things," says Makdes, who stayed in the Calais Jungle for two days before reaching England

Under the Children Act 1989, it is a council's legal responsibility to care for unaccompanied children who arrive in their local authority area.

For some councils, this has presented a particular challenge. Kent County Council is currently looking after 932 unaccompanied migrant children - the largest number among councils in the UK and an increase from 220 in March 2014.

The county council recently claimed, external the "unprecedented" influx was having a negative impact on "citizen" children in its care, and, to accommodate the rise in entrants, buildings have had to be reopened, and some young migrants have been placed out of the county, as far away as Herefordshire.

Unaccompanied asylum seeker children in Kent, which has seen the largest number of applicants

According to Peter Oakford, cabinet member for specialist children's services at Kent County Council, the government reimburses the county council for some of the costs involved in looking after the lone migrant children but, he says, there is still a shortfall.

"Our shortfall was running at £7.5m and is now down to £2.5m," he said.

Mr Oakford says the county council wants the government to introduce a national dispersal scheme, so that when the lone migrant children arrive, they are shared out across the UK.

Another council dealing with a relatively large number of children seeking asylum is Croydon, in south London, where latest figures show the council has 451 unaccompanied children in its care.

Similarly to Kent, the majority of lone children seeking asylum in Croydon are males aged 16 or 17.

What happens?

Unaccompanied children under the age of 16 are generally placed in foster care by the local council.

For those who are 16 or 17 at the time of arrival, some may be placed in foster care but others, like Makdes, are placed in semi-independent accommodation.

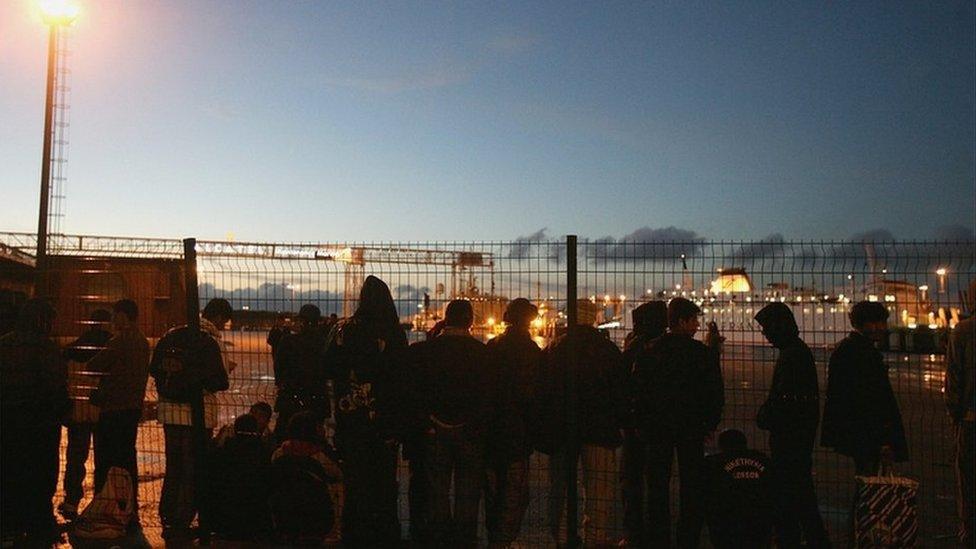

Migrant camp in the jungle in Calais

"My first few weeks were so hard," Makdes said.

"I was just sitting in the house and didn't have anyone at the start to show me where anything was, where to get food. It was really lonely. There was no-one to talk to."

When she arrived in England from Calais, she says the asylum process was "horrible".

"It was so hard. I was so nervous. The lady interviewing me said I was 18, and I was trying to tell her I was 16. I just wanted to go home. I didn't want to argue with her."

For those applying for asylum as children, one of the main issues is age disputes, says Kamena Dorling, head of policy at Coram Children's legal centre.

In the year ending September 2015, 590 asylum applicants had their age disputed and there were 574 recorded as having an age assessment. , external

According to the Home Office, there is no single technique to determine an applicant's age.

"Many children arrive without documentation to prove how old they are and have their age questioned by the Home Office and/or local authority," says Ms Dorling.

590 asylum applicants had their age disputed in the year ending September 2015

"These cases can be long and costly, during which time the child involved often doesn't receive the support they need."

Home Office figures state that in the year up to September, 65% of applicants who underwent an age assessment had a date of birth suggesting they were over 18, external.

Culture shock

For those who are accepted as minors, the next step is going through the asylum process.

Refugee Council figures show that in the first quarter of 2015, 181 UASC (Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children) leave grants were handed out to unaccompanied children, external compared to 98 grants of refugee status, 18 grants of discretionary leave, and 1 grant of humanitarian protection.

Ms Dorling says most children are not granted refugee status but instead are given UASC grants, which are a temporary measure that protect minors until they are 17-and-a-half. Many, she adds, then "find themselves facing removal from the UK once they turn 18".

According to Rebecca Griffiths, who works with trafficked children at Barnardo's, the majority of trafficked minors they deal with are those who have come to the UK unaccompanied and seeking asylum.

"A lot of the children we have dealt with have experienced loss and grief. We've dealt with children who have seen close family members who have drowned in the boats going across the waters to Greece - that's not an unfamiliar story.

"There's also the culture shock and language barriers. They're essentially isolated. It makes it very difficult to build trust.

"They're some of the most vulnerable children in this country."

Asylum seekers stand in front of a fence at the port of Calais

Recruiting foster carers to meet the needs of such children can, says Kevin Williams, CEO of Fostering Network, be a "challenge".

"The number of young people in the care system is increasing and the vast majority are in foster care," he told the BBC.

The Fostering Network says there is an urgent need for more foster homes in the UK, and figures released, external this month estimate over 9,000 more will be needed during 2016.

"Generally, the unaccompanied asylum-seeking children will have suffered some trauma or loss so it's about getting foster carers who understand loss, and making sure they are the right cultural and language fit.

"We think if the government are to commit to taking in more lone asylum seekers, they need to make sure resources are in place to meet that challenge," said Mr Williams.

For the young migrants already here, everyday life in a new country can be daunting.

18-year-old Jetmir, who sought asylum as a minor in the UK from Albania, expresses his uncertainty best through his poetry:

"This is another different country with a different way. I don't know where to go or even what to say.

"I've left my family and my home, I had to make a trip and I have done it alone. I didn't want to leave but people sometimes don't have a choice. The only thing I have is myself and my voice. "

- Published14 January 2016

- Published5 January 2016

- Published28 January 2016

- Published16 December 2015