Can Johanna Konta capture Britain's hearts?

- Published

Will Britain embrace Johanna Konta as one of its own?

As Johanna Konta storms into the semi-final of the Australian Open - becoming the first British woman in 32 years to do so - it would be reasonable to expect a frenzy of excitement across the UK. After all, her family lives in Eastbourne, she holds a British passport, and is displaying a talent and tenacity that have been somewhat lacking in the domestic women's game.

But aside from aficionados of the sport, reaction has seemed a little, well, muted.

Is it because she was born in Sydney, has Hungarian parents and lives and trains in Spain? Or because in addition to her British passport she also has an Australian one and a Hungarian one? Have we accepted her as British? And if not, what will the 24-year-old have to do before we take her to our hearts?

Konta herself identifies as British, even though the Australian press may try to portray her "as a local girl", external.

In a post-match interview earlier this week, when it was suggested she might be emotionally reclaimed by the country of her birth, Konta said: "It's a compliment for you guys to be interested in my Australian roots... but Great Britain is my home. That is where my heart is."

BBC News takes a look at other British sportspeople who were born abroad - and what tips Johanna Konta can glean from the way they were welcomed - or otherwise - by the Great British public.

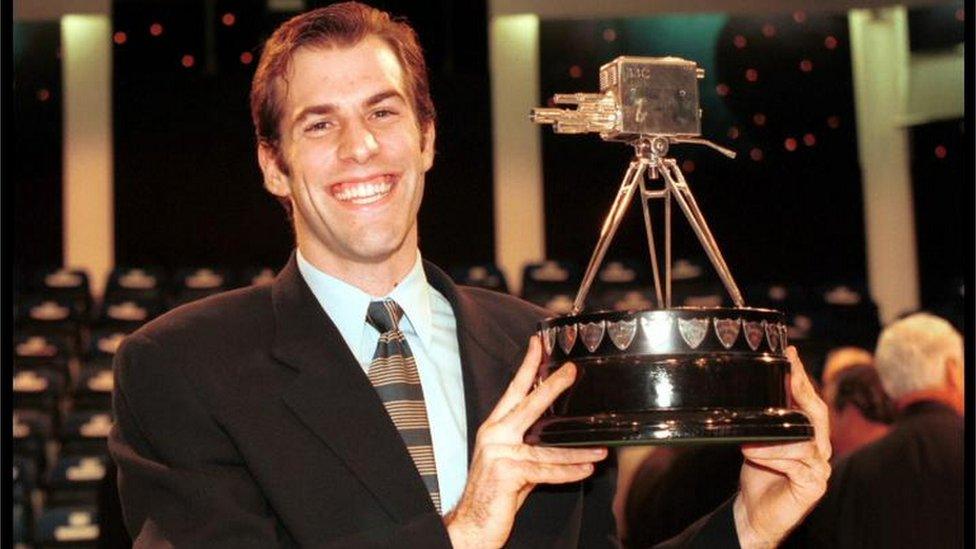

Greg Rusedski

Sticking with tennis, the big-serving lefthander was a Canadian when he reached the top 50 in 1993. But just two years later, by dint of his mother coming from Dewsbury in West Yorkshire, he had swapped the maple leaf for the union jack and played for Great Britain in the Davis Cup.

He was also the first subject of the "British-when-he-wins, Canadian-when-he-loses" quip which has since been tweaked and endlessly wheeled out for Andy Murray (although he is Scottish when he loses, according to the jibe).

"Lennox Lewis with a tennis racquet" became world number four and got to the final of the 1997 US Open, where he lost to Pat Rafter.

The British public seems to love a brave loser though, and getting so near - yet so far - may have swung the vote in Rusedski's direction, as later that year he was crowned BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

And do accents and names matter? Rusedski has a distinct Canadian twang; his rival and contemporary Tim Henman - of the cut-glass vowels and solid English-sounding name - is probably remembered more fondly. After all, Wimbledon's Henman Hill persists while Rusedski Ridge does not.

The Canadian-born star's name is not Anglo-Saxon and was even mispronounced as "Rudeski" when receiving the SPOTY trophy. Konta's accent is not quite Australian, not quite English. And her first name is pronounced Yo-hann-uh rather than the English Johanna.

So for mass adulation, maybe Konta should get to the final - and lose (bravely), work on her vowels and call herself Jo.

Lennox Lewis

Born in London to Jamaican parents, Lennox Lewis (never described as "Greg Rusedski without a tennis racquet") moved to Ontario, Canada, when he was 12.

Lewis subsequently won both the world amateur junior title and an Olympic heavyweight gold for Canada, enough for some British fans to consider him conclusively Canuck.

But he says he always felt British, and he returned to the country of his birth as soon as he turned professional. Although some boxing fans never forgave him his Canadian inflection, he is another winner of BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

Konta has the advantage over Lewis in that she has only ever represented Great Britain in team competition the Fed Cup, external.

She still needs to work on that accent, though.

Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome

Yes, sideburn-sporting Paul Weller fan Sir Bradley Wiggins is not English by birth. He was born in Ghent, Belgium, to an Australian father and English mother.

He was raised in London though, and started racing in the city aged 12, and when winning the Tour de France described himself as "a kid from Kilburn".

He is another winner of BBC Sports Personality of the Year and is widely regarded as a national treasure.

Chris Froome, on the other hand, seems to be more admired than liked. His hugely impressive victories in two Tours de France were greeted with much less excitement - and even suspicion - than than the more charismatic Wiggo's.

There is also the perception that he is not "properly British". He was born in Kenya, raised in South Africa and lives in Monaco.

Can Konta emulate Wiggins? Sideburns-wise, probably not. But she is a big music fan, going to see Taylor Swift the Saturday before Wimbledon.

Owen Hargreaves

Born in Canada to an English father and Welsh mother, Hargreaves spent 10 years at Bayern Munich, before moving to Manchester United, external.

But Hargreaves always insisted he "felt English", and went on to become the first player to be capped by England having not previously lived in the country.

It took until he carried, external Sven Goran Eriksson's men through to the 2006 World Cup quarter-final against Portugal (Wayne Rooney was sent off and they lost on penalties), for English fans to warm to him.

Maybe a spectacular team performance in the face of adversity by Konta could propel her further into the hearts and minds of fans.

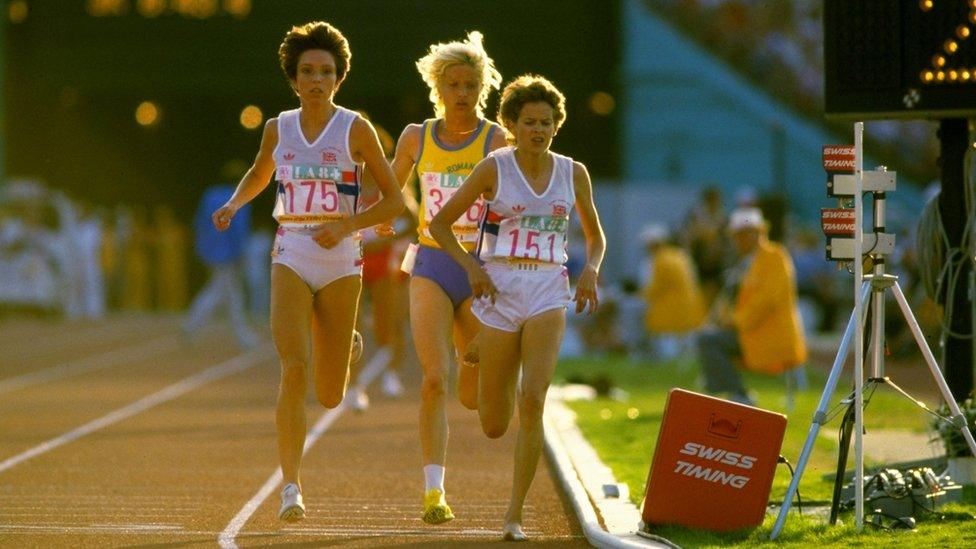

Zola Budd

Barefooted 17-year-old runner Budd was not only South African born and bred but openly admitted choosing to compete for Great Britain at the 1984 Olympics (where she appeared to make golden girl Mary Dekker trip over, external) because South Africa was banned from competing.

According to British Athletics, external, her transfer of nationality was "an incredible, cloak-and-dagger operation" facilitated by the Daily Mail.

"The newspaper sent its athletics correspondent and a news reporter out to watch her run, him reporting back to the editor of what a talent she was and then her and her family being brought back to England in a hideout in the south coast.

"Suddenly, it was front page news. They had allegedly paid £100,000 to secure the story and amid much controversy, she was fast-tracked to British citizenship," the organisation said.

The public did not take to her. She was a white South African from a racist nation, using a technicality - her grandfather's English birth - to pursue personal ambition.

When the country was allowed back into international competition, Budd ran for South Africa.

Tips for Konta? Stick to her promise to remain British.

Kevin Pietersen

Another South African who went on to compete for England, Pietersen also transferred allegiance over race relation issues - this time because of the quota system in his home country.

The system was brought in to give more opportunities to black South African cricketers after years of Apartheid. It means a team is asked to field a certain number of black players.

Pietersen said: "It doesn't give white people the fair opportunities they should have.

"So I saw my opportunities in the UK, where selection is merit-based."

Again, like Budd, Pietersen is clear that he chose to surrender his South African nationality for personal achievement. Unlike Budd, he amassed great public favour - partly by scoring a maiden Test century with the Ashes at stake, external.

An individual talent in a sport that values the team ethic, there was an outcry when he was not chosen to play in the Ashes in 2015. But the team managed without him.

His personality, which has never been called "humble" but has on occasion been described as "abrasive" and "troublesome", also earned him some enmity and dented his popularity.

Konta has humility in spades, not least in acknowledging she needed psychological aid: "You need to be humble, and to accept that a mental coach can help you.

"You also need to be courageous to try different ways of thinking and behaving."

- Attribution

- Published27 January 2016