Spitfire funds: The 'whip-round' that won the war?

- Published

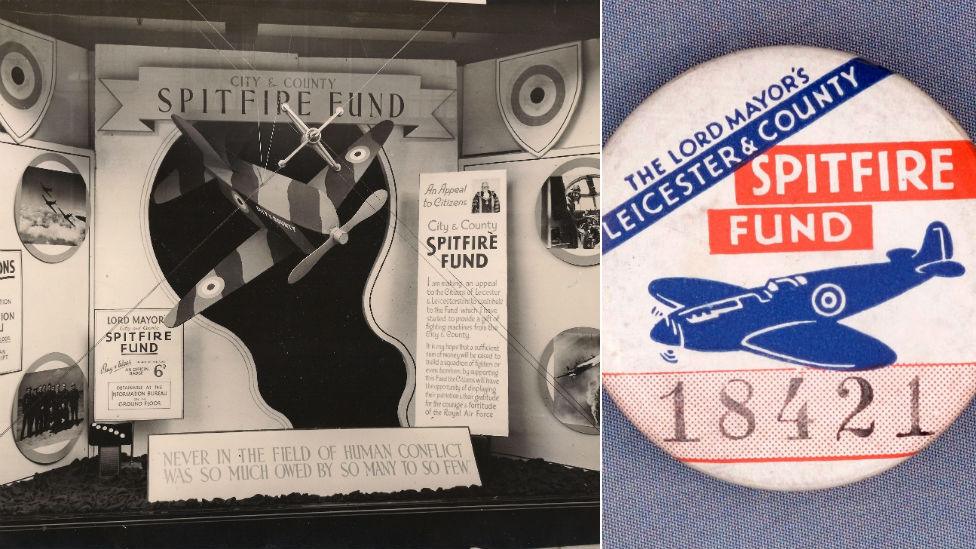

The campaign was backed by posters and newspaper articles

The power and the glamour of the Spitfire would make the aircraft a firm favourite from almost the moment it first flew, in March 1936. Eighty years on, the Spitfire remains one of the most admired of all fighter aircraft, but the story of its unique connection with the British public - who dug into their own pockets to pay for its production - is less well-known.

"When my mummy has taken me out and I have wanted to use a public convenience she has had to pay a penny. So I thought if we did the same at home it would help your fund."

So wrote eight-year-old Patricia Boncey to Lord Beaverbrook, Minister of Aircraft Production, to accompany her postal order for 15 shillings.

"The Spitfire funds were a home front phenomenon," says aviation historian Paul Beaver.

The 80th anniversary of the Spitfire's first flight

"The aircraft, and the idea of buying one, seemed to hit the national psyche.

"Britain wanted to believe in something and the Spitfire, that combination of beauty and power, was the great saviour."

Almost from the moment it took to the air in 1936, the Spitfire inspired movie star-style attention, overshadowing the contemporary Hurricane fighter.

This ability to amaze and inspire was embodied by the fund movement, which obsessed much of Britain and beyond.

Funds were everywhere, with contributors being rewarded with badges

Donations ranging from pocket money pennies to king's ransoms eventually raised about £13m (£650m at modern values).

But the story behind this generosity was one of crisis, improvisation and a pushy Canadian.

War is an expensive business and 1914-18, coupled with the Great Depression of the 1920s, had left Britain saddled with huge debts.

The policy of avoiding war by making concessions to Hitler - known as appeasement - was in part prompted by a national bank balance firmly in the red.

Spitfire fact file

First flight: 5 March 1936

Entered service: 4 August 1938

Max speed: (Mk1 at 15,000ft) 346mph (557km/h)

Dimensions: (Mk1) wingspan: 36ft 10in (11.2m), length: 29ft 11in (9.1m), height: 11ft 5in (3.5m)

Armament: (Mk1) 8 Browning .303 machine guns

Numbers built: 20,351

Last RAF operational flight: 1 April 1954

But as the ambitions of Nazi Germany became clear, there was a scramble to rebuild the neglected armed forces.

In early 1940 Lord Beaverbrook - the Anglo-Canadian media tycoon Max Aitken - came into government to speed up aircraft production.

Beaverbrook pushed the idea of public appeals, for example to source raw materials and to encourage thrifty shopping, in a bid to help with the war effort.

Viewing crashed German aircraft was a favourite way to raise money for Spitfire funds

Breathless press coverage of the Spitfire brought unsolicited enquiries about helping get more planes in the air.

The two ideas came together. In May 1940, Spitfire funds took off.

The aircraft were priced at an entirely theoretical £5,000.

Within weeks funds were set up by councils, businesses, voluntary organisations and individuals.

Sleek Spitfires dazzled a public used to aircraft that resembled World War One biplanes

Fired by the sight of German planes overhead during the Battle of Britain, more than 1,400 appeals were set up.

Many were co-ordinated by local newspapers, which carried lists of individual donations: "From all at No.15 Station Lane", "My week's pocket money - Fred Smith aged 7″, "My first week's old age pension - 10 shillings towards our Spitfire".

Matt Brosnan from the Imperial War Museum says: "Quite quickly the BBC was listing the latest successful funds and major donations at the end of news bulletins and takings were averaging over £1m a month.

"Almost every big town in Britain came to have its name on a Spitfire by the end. Even anti-aircraft batteries and aircraft factories contributed. The miners of Durham contributed two Spitfires, even though suffering with heavy unemployment."

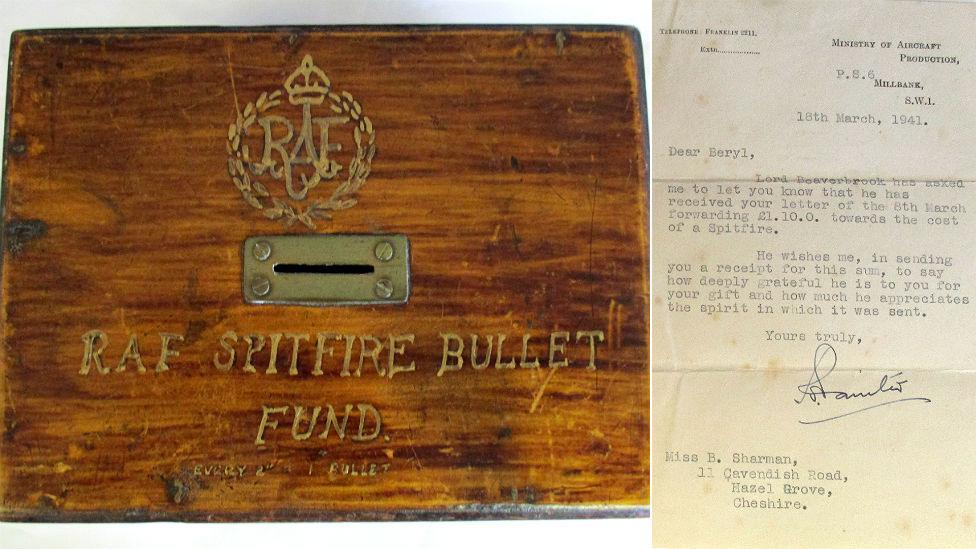

The funds were designed to give people a sense of being part of the war effort

To encourage the idea every penny counted, a components price list was published, included a wing for £2,000, a gun at £200, down to a spark plug at 8 shillings, or a rivet at sixpence.

Imagination and dedication led to countless fund-raising ideas. Everyone could "do their bit".

A Kent farmer charged people sixpence "to see the only field in Kent without a German aircraft in it".

Every appeal was a photo opportunity for propaganda at home and abroad

During an air raid, the manager of a London cinema pushed a wheelbarrow up and down the aisle, asking for donations: "The more you give, the less raids there will be". There were table-top sales, auctions and raffles.

The Wiltshire village of Market Lavington drew the outline of a Spitfire in the square and challenged residents to fill it with coins. The task was completed within days.

In Liverpool, it was reported a "lady of the night" left £3 at the police station "for the Spitfire Fund", this amount being the standard fine for soliciting.

Donations came in all sizes and from countless fundraising ideas and events

Another part of the magic mix of the Spitfire funds was contributors could have a dedication of their choice put on the Spitfire. This would be commemorated with a plaque and photograph of the named Spitfire.

The results veered between the mundane, hilarious and downright mysterious.

Those cinema donations resulted in no less than four "Miss ABCs".

The Kennel Club called its Spitfire 'The Dog Fighter', while Woolworths named "Nix Six Primus" and "Nix Six Secundus" after its pre-war policy of keeping prices below sixpence.

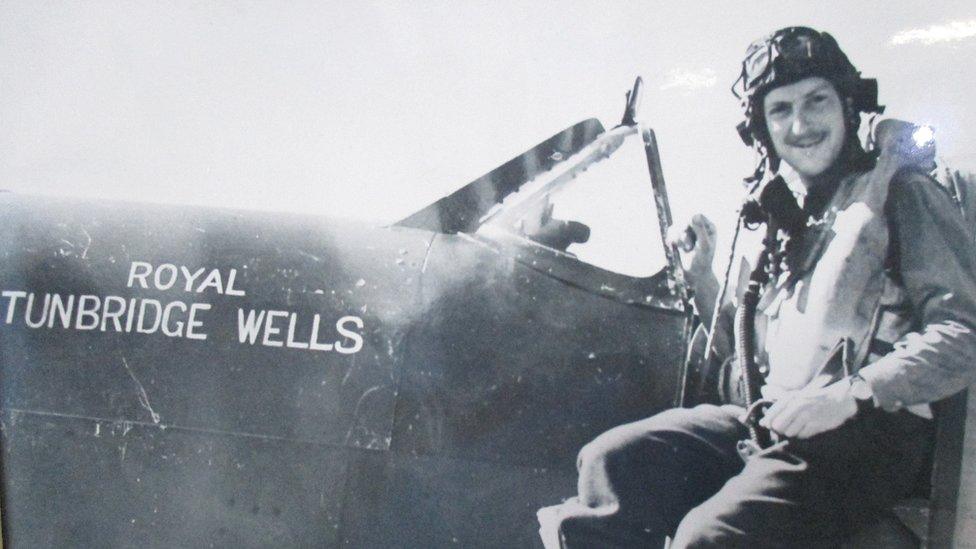

Many Spitfires were simply named after the places that had raised the money

Remarkably, even prisoners of war got in on the act. Inmates of Oflag VIB donated a month's pay and, via the Red Cross, it went to "Unshackled Spirit".

It was truly a global appeal.

Spitfire "Dorothy of Great Britain and Empire" was paid for by a fund made up entirely of women and girls of that name. Uruguay, diplomatically neutral, funded 17.

Many countries donated enough for entire squadrons to bear their name, including No.74 (Trinidad), No.167 (Gold Coast) and No.114 (Hong Kong).

Others, like this from circus performers, were more creative

Some stories are more poignant. The small communities of Holmesfield, Derbyshire and St Michel-le-Pit in south Wales somehow raised the money to pay for Spitfires named 'Shepley' and 'Norman Merrett' in honour of bereaved local families.

Spitfire "Fun of the Fair" was named after an appeal by various circuses, fairgrounds and carnivals, set up in a bid to counter accusations the travelling community was shirking war duties.

Not everyone took the scheme in the intended spirit. In August 1940 a building worker from Ilford was jailed for running fake Spitfire funds.

Local rivalries ran deep. One councillor Arnold Ingham warned colleagues "If we should have a dogfight over Lytham St Annes let us have a Spitfire of our own to deal with it and not have to send to Fleetwood or Blackpool to borrow theirs."

A member of the Naafi mobile refreshment service presents a pilot with "Counter Attack"

The funds raised enough for about 2,600 Spitfires but incomplete records mean fewer than 1,600 can be traced.

The RAF had about 300 Spitfires fighting in the Battle of Britain at any one time, with total combat losses estimated at about 260.

By the end of 1940, factories were turning out up to 350 a month.

But did the funds make a difference to the war?

This photograph has been alleged to show a name that was temporarily chalked on the plane

Mark Harrison, professor of economics at the University of Warwick, says the answer has echoes in the present.

"Only after ensuring the supply of Spitfires did the government worry about how to pay for them.

"The funds were like today's 'sponsor a panda' and 'buy a metre of rainforest' appeals. In any immediate sense these make no difference to the number of pandas or the amount of rainforest.

"Spitfire funds did not pay for Spitfires, but they were still an essential part of the war effort.

"Without them the war would eventually have gone less well in one aspect or another. There would have been a cost."

- Published5 March 2016

- Published5 March 2016

- Published18 August 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published19 February 2012