Celebrating Shakespeare - why bother?

- Published

As the 400th anniversary of his death approaches, why should we bother celebrating Shakespeare? After all, he was only a playwright. And we don't take to the streets to whoop it up for Chaucer, Jonson or Bacon.

Shakespeare has a reputation as being the preserve of the trite middle classes who like to shoehorn a misquote or two into ordinary conversation. Or students swotting over King Lear for their GCSEs.

Indoctrination (his work is compulsory on the National Curriculum for English, external) and a fear of appearing uncultured may lead people to keep quiet about their antipathy or indifference, leaving the way clear for "bardolators" to indulge.

Yes, he was a talented chap - but how did Shakespeare become the "fifth greatest Briton", external of all time?

David Garrick was considered one of the best Shakespearean actors and was painted by William Hogarth

Not everyone has been bowled over by the bard.

Shakespeare sceptics included Alexander Pope, Voltaire, Lord Byron, Tolstoy and George Bernard Shaw.

Byron proclaimed: "Shakespeare's name, you may depend upon it, stands absurdly too high, and will go down," while Tolstoy called him "a bombastic hack".

Wittgenstein wrote: "When I hear expressions of admiration for Shakespeare made by the distinguished men of several centuries, I can never rid myself of a suspicion that praising him has been a matter of convention," while Voltaire called the bard's work "an enormous dunghill".

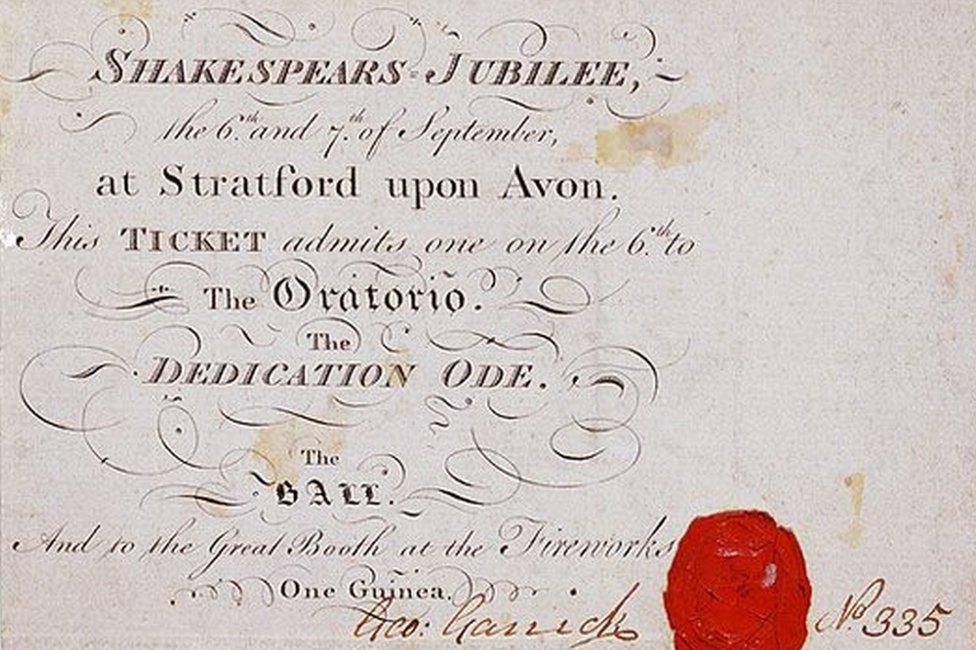

A souvenir medal and ribbon for David Garrick's "Shakespeare Jubilee" of 1769

Professor Ewan Fernie, head of Shakespeare studies at the University of Birmingham, says it's a good thing to question "why we should celebrate Shakespeare rather than play video games or get drunk".

The reason we should is "because Shakespeare offers one of the richest experiences in human culture - it's not just for exams or degrees, it's a stimulus to cultural and political life", he says.

For more than 150 years after his death though, Shakespeare's work was merely well regarded - until, in September 1769, the celebrated 18th Century actor and playwright David Garrick put on a three-day festival.

It was intended, albeit five years late, to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the playwright's birth.

His location of choice was Stratford-upon-Avon - and the event not only helped turn the Warwickshire town into the tourist magnet it is today, but puffed up Shakespeare's reputation from "dramatist" to "demigod".

Prof Fernie says Garrick's Stratford Jubilee "wasn't just the first major Shakespeare celebration, it seeded all others".

A scene at the High Cross in Stratford-upon-Avon during the Garrick Jubilee

"It was a happening, mocked and marvelled at, ideologically disorganised, susceptible to different interpretations, and yet, if only we have eyes to see it, instrumental to the association of Shakespeare with freedom that proved important to western modernity and might still provide us with a credible, substantial and interesting reason for celebrating Shakespeare today."

In retrospect, Garrick's jubilee was a bit odd - in that no Shakespeare was performed.

It's something we wouldn't get away with today, Prof Fernie says.

Instead, the centrepiece of the event was an ode, written and performed by Garrick (who was something of a show-off) plus a procession of people dressed as Shakespeare's characters (the celebration was marred by rain).

Prof Fernie says: "Garrick celebrated Shakespeare not so much as literary heritage to be preserved against the depredations of time and change, but instead as example and inspiration. He celebrated Shakespeare as the very quintessence of freedom, as the proof and promise of new life."

Shakespeare then, can be seen as an agent for political agitation - and theatres are excellent places for making a rowdy stand, something that still happens today.

One of the most disgruntled groups in society in the mid-19th Century were the industrial workers, out of which the Chartists emerged.

Arguably the country's first organised mass working-class movement, they used Shakespeare as a hero.

This printed ticket reads: "Shakespears Jubilee, the 6th and 7th of September, at Stratford upon Avon. This ticket admits one on the 6th to The Oratoria, The Dedication Ode, The Ball and to the Great Booth at the Fireworks. One Guinea"

According to Anthony Pennino, a professor of literature at the Stevens Institute of Technology, the Chartists "tried to frame British history and culture in terms of an ongoing class conflict" and within the conflict would pick certain famous people as voices of support to working-class causes.

"In reclaiming the past for themselves, the Chartists hoped to influence contemporary political debate and place their ideology before the people using whatever media - newspapers, parades, speeches, theatrical events - at their disposal," Prof Pennino said.

An extraordinary 100,000 people marched to Primrose Hill in north London in 1864 to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth.

Organised by the Workingmen's Shakespeare Committee, which teamed up with the Trades Provisional Committee, the rally included planting a tree "in the name of the workmen of England" by the Shakespearean actor Samuel Phelps.

The committee planned to raise money for a huge statue of the playwright to be erected - although this didn't materialise.

The organisers claimed to want a festival of labour and democratic reform which challenged the pro-establishment and pro-Empire tone of the National Shakespeare Committee.

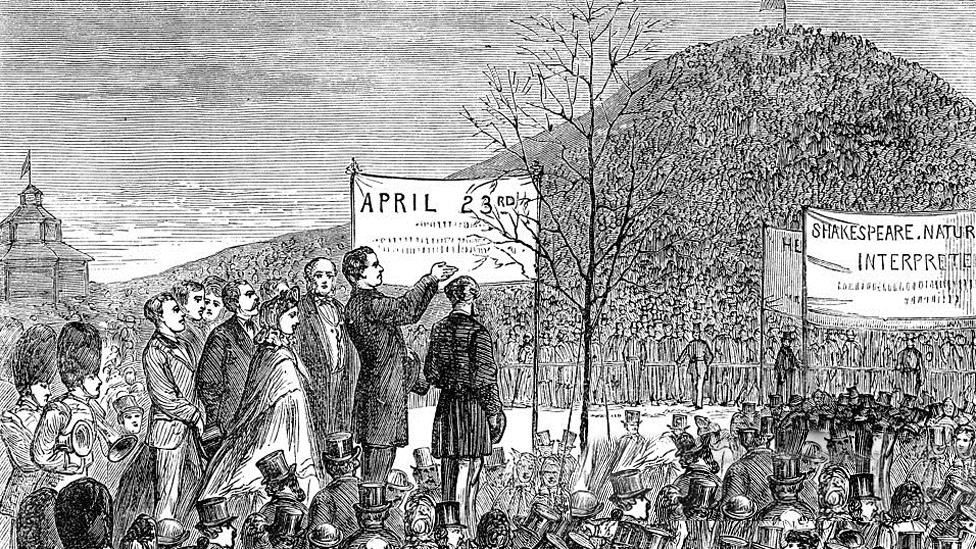

About 100,000 people gathered to watch the planting of "Shakespeare's oak" on Primrose Hill in 1864

However, many of the members of the Shakespeare Workingmen's Committee were also on a Garibaldian Committee, which feted the Italian nationalist, who'd been a key player in the recent unification of Italy.

He visited Britain in 1864 and provided inspiration and a battle-cry for English radicalism - but his overwhelming popularity worried the British government and it was made clear he was no longer welcome.

The Shakespeare event on Primrose Hill - which had been approved by the authorities - morphed into a protest, external about Garibaldi's departure - a rally which hadn't been approved by the authorities and was eventually broken up by police.

So once again, Shakespeare was used as a vessel for protest.

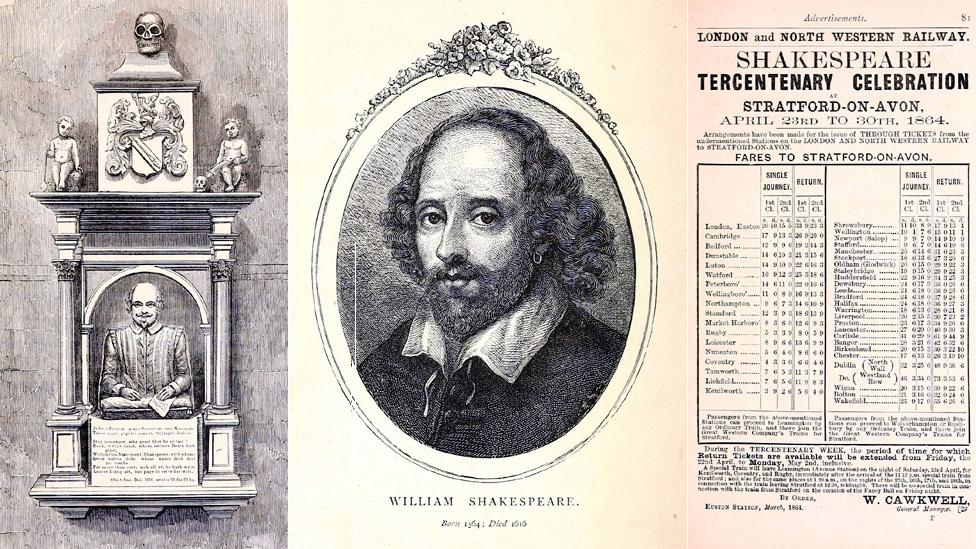

A printed programme was produced for the tercentenary celebrations, which included engravings of Shakespeare's bust, and a timetable for specially laid-on trains from across the country

The suffragettes were also keen to claim Shakespeare, latching in particular on to The Winter's Tale character of Paulina, who rails against injustice and stands up to an unfair king, when his acolytes are too timid to do so.

"Shakespeare was seen as a pillar of the establishment, enormously popular in the UK and a symbol of its values in the Empire," says librarian Sylvia Morris, a Shakespeare researcher and writer.

"Being able to say that Shakespeare was on their side was a great plus for the suffragettes, struggling to be taken seriously by the political establishment."

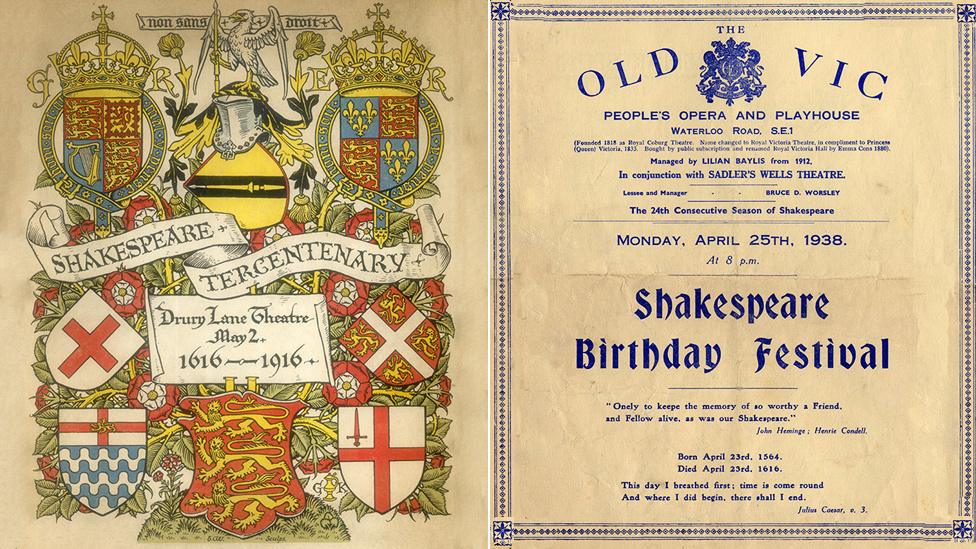

Although overshadowed by war, the anniversary in 1916 was still marked

The tercentenary of Shakespeare's death, which fell in 1916, was marked in Drury Lane with a special theatre performance.

The eulogy in the programme's preface acknowledged the shadow cast by the Great War:

"In honour of Shakespeare this performance has been arranged by actors, painters and musicians who have united in paying such tribute as lies in their power to the Master-Intellect of the ages.

"To all artists the memory of the Great Englishman is as dear as to those who recall with gratitude his patriotic love of his native land… for all his countrymen alike the deathless art of Shakespeare - especially at a time like this, so unpropitious to the higher levels of imaginative creation - is at once a vindication and a pledge that Art itself is immortal".

Prof Fernie says celebrating that "Great Englishman" and his "deathless art" should not be a retrospective activity, but a proactive one.

"It's not for us to simply preserve Shakespeare, there is still lots to learn. It's a form of drama that's democratic - in his plays there's no visible author, no overbearing authority. It's the characters' interaction and the sense of them working the world out together.

"Celebrating Shakespeare shouldn't commemorate the past - it should stimulate the future."