Who deserves a blue plaque?

- Published

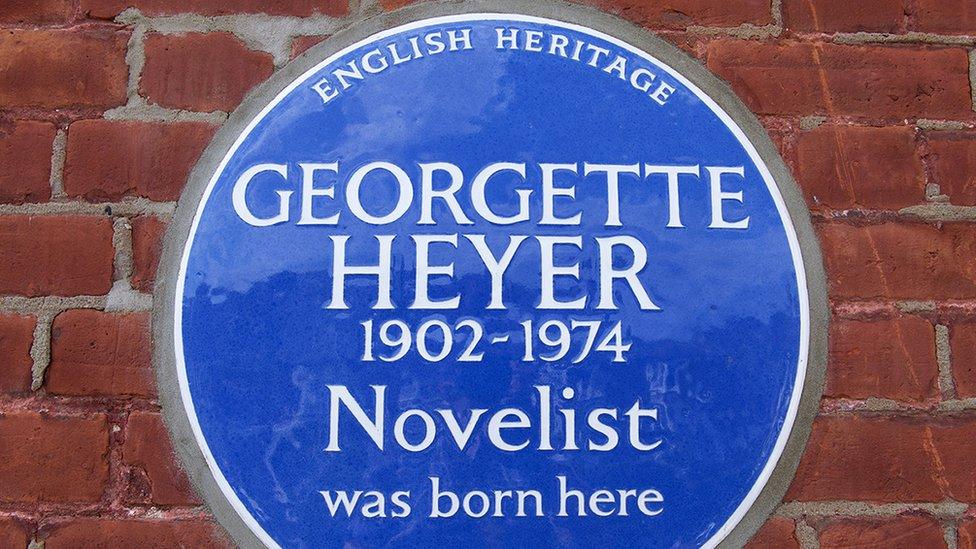

There are thousands of heritage plaques installed by hundreds of different organisations across the country

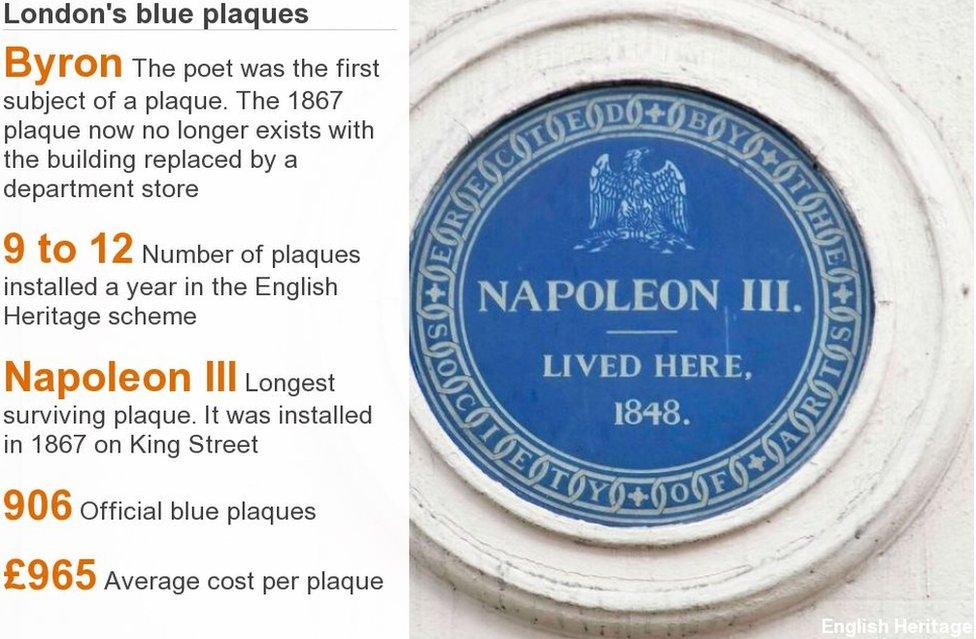

England's first blue plaque scheme started with a tribute to a controversial poet in 1867 and now, almost 150 years later, it has celebrated by unveiling a plaque to a food writer. So who qualifies for a plaque?

The country's first blue plaque no longer exists - the disc marking 24 Holles Street as the birthplace of Romantic poet Lord Byron was removed when the building was replaced with a department store.

But the scheme started by the Society of Arts is still going strong, and has been replicated in hundreds of towns and cities around the country.

Even within the capital there is a plethora of plaques by other organisations, but the original programme, now managed by English Heritage, has seen more than 900 installed, the latest of which was to food writer Elizabeth David.

And they are very strict about who gets a plaque.

Recipients must have been dead for at least 20 years and must have lived at the location they are being connected with for either a long time or during an important period, such as when writing their seminal work or creating their key invention.

"The 20-year rule is quite important to us," said Alexandra Carson, national PR executive for English Heritage.

"It gives us the benefit of hindsight and allows us to better judge their long-term legacy.

"Also, the building has to be the same as it was when they lived there because a big part of it is bringing history to life.

"It's a really nice way of detailing the history of London and linking people and places."

Elizabeth David's plaque has been celebrated by those who recognise the food writer's influence

There are thousands of blue plaques around England noting significant people and the places they were born, lived, worked, visited or died.

But, as there is no national body governing such commemoration, the criteria used to determine who and where gets a plaque vary widely from place to place.

It is left to local councils, charities and history organisations to police the plaques issued in their areas.

Outside of the original scheme, the majority of plaques can be loosely grouped into four categories: birthplace, residence, visited by and place of death.

For example, a house on Prince's Street in Bishop Auckland is marked as a childhood home of Stan Laurel; Guy Fawkes' birthplace in York and the home of his parents are both labelled and the house in Southwark where Boris Karloff was born has a plaque - it is now a fish and chip shop.

Perfecting the plaque

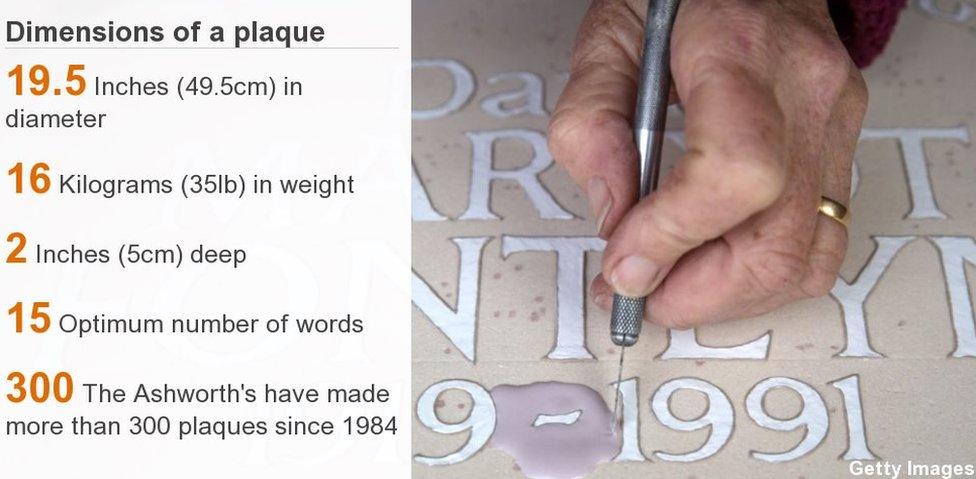

Sue and Frank Ashworth have made more than 300 plaques since 1984

Cornwall-based ceramicists Frank and Sue Ashworth have been making the plaques since 1984.

It is a painstaking process of precision and patience, Mrs Ashworth says.

"You owe it to the person named on the plaque to get it right, and people will notice if anything looks wrong, the finished plaque has a beauty and symmetry about it."

The font was designed by Harry Hooper and each plaque, made from a secret mixture of clays, takes about three and a half weeks - assuming there are no mishaps.

"Things do go wrong occasionally, for example a crack might appear," Mrs Ashworth said.

"On one occasion I forgot to put the English Heritage logo on, another time we were given the wrong dates. They could be salvaged though without having to remake them."

Each letter is made by hand and the plaque goes through two three-day long firings in kilns reaching 1,200C (2,192F).

The couple, who have since been joined in the business by son Justin, have made more than 300 plaques for both schemes and private individuals.

"You have to be very patient but it is enjoyable. Some people might think it is repetitive but as soon as you see it that way you are done."

For some places, fleeting visits are as worthy of note as long-time residence.

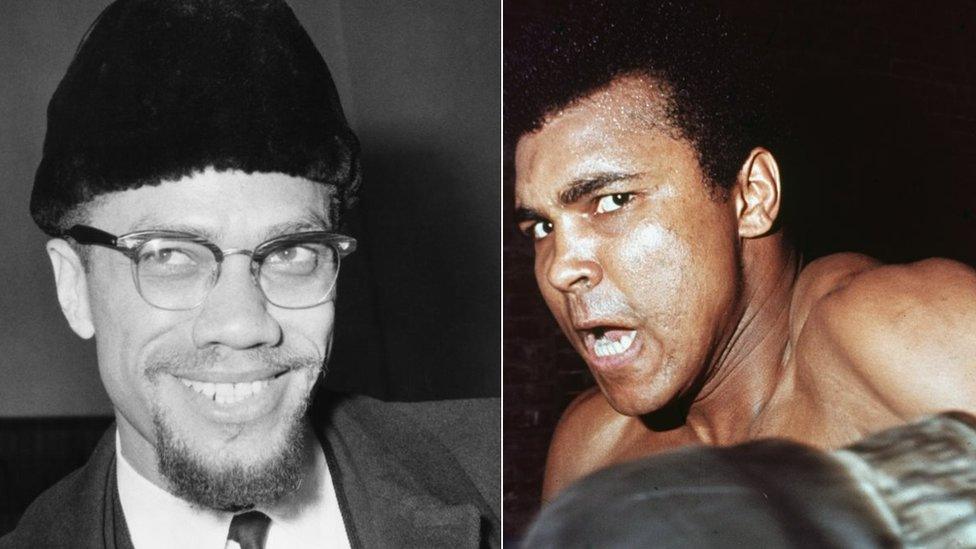

Malcolm X's visit to Marshall Street in Smethwick in the West Midlands nine days before his assassination in 1965 is commemorated, while in Norwich there is a plaque marking the day in 1971 when Muhammad Ali visited a supermarket as part of a promotional tour by Ovaltine.

Malvern is home to a number of plaques marking famous visitors.

There are plaque's in Smethwick and Norwich commemorating visits by Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali respectively

There is the inn where Chronicles of Narnia creator CS Lewis "frequently met literary and hill-walking friends", the favoured hotel of exiled Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie between 1936 and 1941 and the rooms used by a seven-year-old Franklin D Roosevelt when he convalesced in the town in 1889.

"Our plaques are for people and places that had an impact on the history of Malvern," said Brian Iles from the Malvern Civic Society.

"But they are not just for people who everybody knows, we also want to introduce important people who everybody should know about.

"We want to celebrate our history and make sure people don't forget it."

Florence Nightingale and Charles Darwin are also commemorated for having visited Malvern for hydrotherapy in the town's famously low-mineral water.

When it comes to being remembered for visits, Dickens is one of the most prolific subjects with at least 44 plaques around the country, including at the Portsmouth house where he was born, the Barnard Castle rooms where he spent two nights in 1838 while researching Nicholas Nickleby and the Assembly Rooms in Scarborough where he gave readings in 1858.

There are even plaques for his characters such as in Market Square in Dover where David Copperfield apparently "rested on the doorstep and ate a loaf" while searching for his aunt Betsey Trotwood.

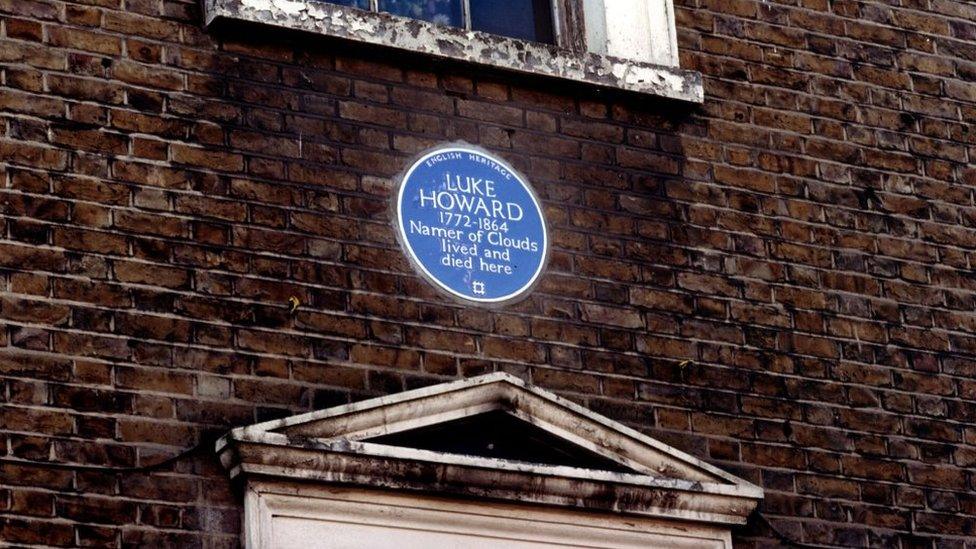

Some of the more interesting plaques are to people many have not heard of, such as Luke Howard, namer of clouds

There are two chief types of people being commemorated - famous figures, such as actors, writers and politicians, and relative unknowns who invented, created or achieved something remarkable.

"The majority fall into the second category," said Ms Carson.

"Being famous is secondary, it is more about what they contributed to society and whether that is worthy of being commemorated.

"And that's what really makes the plaques so interesting, it's people you haven't heard of but who have made some giant contribution to our lives."

One such example is on the former home of meteorologist Luke Howard in Tottenham who invented the names given to clouds.

His inscription simply reads: "Namer of clouds".

Life in a plaque house

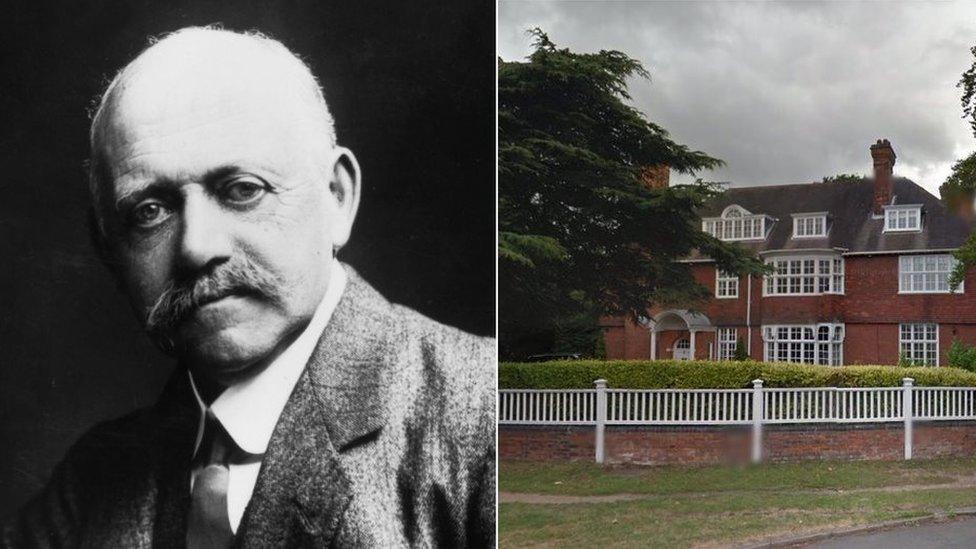

William Willett's former home in Chislehurst sports a blue plaque to him

Since 2007 Walle Ogunyemi and his family have lived in Chislehurst at the former home of William Willett, renowned house-builder and the initiator of British Summer Time.

A plaque to Willett was installed in the 1970s and Mr Ogunyemi said several people a week stop to look at it.

"It's an honour to live there with the history associated with the property," he said.

"You get used to people standing and staring at your home, we allow two or three people in a year from the local history society or relatives of William Willett.

"But people standing outside have never really bothered us, they are always very polite and there is never any malice."

In Birmingham there are plaques to the inventor of plastic and the discoverer of oxygen, while Norwich has commemorations for Britain's first black circus owner and the woman who devised one of the most famous methods of teaching music.

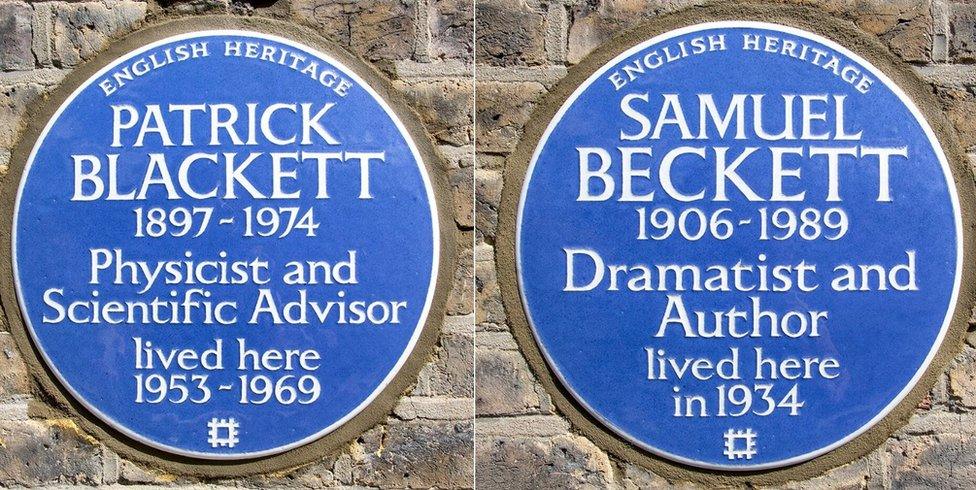

In very rare cases a property becomes a "double-plaquer", having hosted two notable people.

A house on Paulton's Square in Chelsea was the home first of playwright Samuel Beckett in 1934 and then, from 1953 to 1974, physicist Patrick Blackett.

A house in Paulton's Square in Chelsea became the 19th property in London to become a double-plaquer

Places from moments in history are also often commemorated with plaques.

For example, Frome station has a plaque celebrating the fact that Leonard Woolf took the 10.29 train from there to London, on 11 January 1912, to propose to writer Adeline Virginia Stephen, later known as Virginia Woolf.

In Saltburn there is a plaque commemorating the world speed record attempts made by members of Leeds and Middlesbrough Motor Clubs on the beach in the early 20th Century and in Wolverhampton the country's first set of traffic lights are celebrated.

Although the plaques are awarded by organisations, they are more often than not suggested by the public.

"We look at every application," Ms Carson said.

"We are always looking for new and interesting people worthy of being remembered."

- Published13 May 2016

- Published20 April 2016

- Published1 March 2016

- Published25 February 2016