The kindness of strangers: Are good Samaritans the exception or norm?

- Published

If you saw someone being attacked on the street, would you help? Or would you reason that it's none of your business and walk on by?

Britain has been called a "bystander society" but recent events demonstrate people are prepared to go to the aid of those who need it.

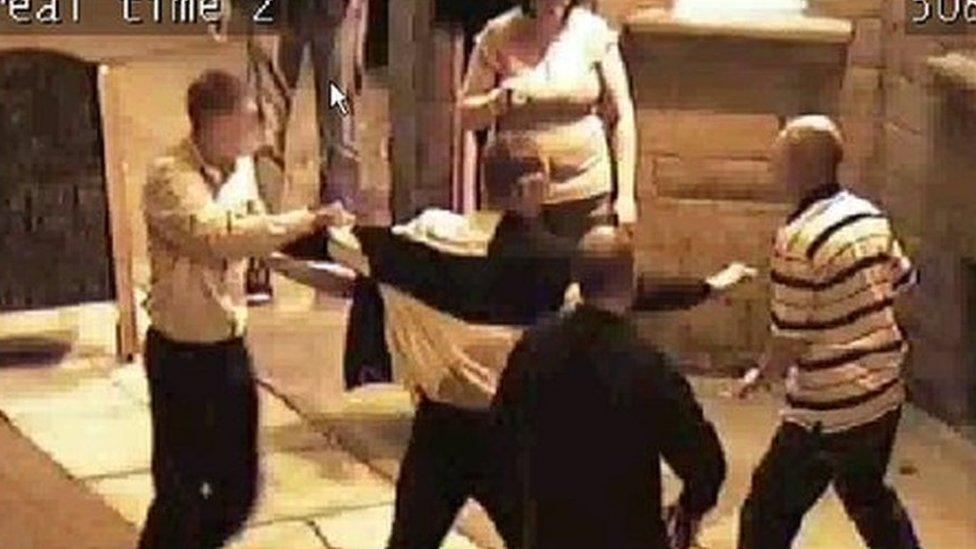

Babur Karamat Raja, a 41-year-old company director, has been jailed for 18 years for the attempted murder of his pregnant partner in Birmingham. Natalie Queiroz survived, a court heard, because of the intervention of passers-by.

Raja repeatedly stabbed Ms Qeuiroz until two men intervened and wrestled him to the ground. A third man joined in to try to stop the attack. Four teenage boys then helped by dragging Raja away.

This kindness of strangers has been repeated around the country.

Bernard Kenny has been deemed a hero for trying to save MP Jo Cox from a deadly attack in Birstall. Triple killer Joanne Dennehy would have claimed another victim if passers-by in Hereford hadn't stopped to help John Rogers.

These are the "have-a-go heroes" we hear about - and we react as if their actions are not only brave, but out of the ordinary.

But according to research, we're more likely to intervene than perhaps we expected.

The first image shows Babur Raja concealing a rucksack containing a knife under his hoodie

It may seem counter-intuitive, but a person alone is more likely to get involved than people in a group, despite the idea of there being safety in numbers.

A person witnessing an attack goes through a very rapid unconscious thought process which decides whether they get involved or not, says Prof Mark Levine, a social psychologist at Exeter University.

"In such a scenario, someone's mind flicks through numerous calculations almost instantaneously.

"Is this dangerous to me? If I intervene, can I actually help? Will others support me if I do this, or will I be embarrassing myself in some way? What's my responsibility to the victim?

"The longer you leave it, the harder it is to make a decision. If you don't immediately act then you kind of think 'Well, actually I probably couldn't have done anything anyway'."

An important element is the social construct people put on the relationship between the assailant and victim.

In the above cases, it's very clear there was something wrong. The victims were being attacked with weapons, in broad daylight. That, according to Prof Levine, makes some of the unconscious decisions easier - as there's a low risk an intervener could be interpreting the situation wrongly.

John Rogers was stabbed multiple times by Joanne Dennehy. Police say passers-by saved his life

If the attack had been between two men outside a pub at night, people would be much less likely to get involved.

Factors like the weather, the location, the types of people passing and how the person in trouble is dressed can all affect the situation.

People are much more likely to intervene if they feel some sort of group kinship with the victim, even something as superficial as wearing the same football shirt.

The seemingly obvious possibility that people are simply too frightened to intervene is discounted by psychologists, as the "fight or flight" mechanism overrides rational thought.

They point out that if this were true people would be less likely to "have a go" if they were alone, whereas the opposite is the case.

Case study: Jemma, Leeds

I have intervened more times than I care to remember with my earliest memory being at school. I intervened once when I was about 15 or 16. A boy was being attacked on a station walkway, he was only 11 or 12.

Commuters were just walking past, they could all see him and yet I was the only one to stop. My actions resulted in the boy getting away and I was pinned to the wall by my throat.

Would I have walked on by if I had know what was going to happen to me? Never.

The way we interpret the psychological and societal relationships is the most important factor when it comes to whether we intervene, says Prof Levine.

He gives the example of being in a supermarket and seeing an man smack a toddler. While we may disapprove, it's unlikely we'd interfere as we'd assume it was a parent and their child.

But if we saw the man hit a woman, we'd be more likely to try to stop it - despite the level of violence being the same - because the social constructs would kick in.

At least 38 people saw James Bulger with his killers, but assumed they were his family

A famous 1976 experiment, external found that people would also be more likely to help a woman if they believed she was being attacked by a stranger rather than by her husband.

Test subjects were left outside a lift, where they could hear a physical altercation between a man and woman, played by actors.

Half the time, when the lift doors opened, the woman would say: "Get away from me, I don't know you". The other half of times she'd say: "I wish I'd never married you".

The idea that the pair were a couple negated the subjects' instinct to step in and help.

Prof Levine studied the witness reports in the case of James Bulger. The toddler was seen with his killers Robert Thompson and John Venables by 38 people.

All 38 assumed the three were brothers and, because they believed it was a family unit and they were outsiders, they didn't feel able to approach.

The issue is, Prof Levine says, whether we consider a family as responsible for one other, or whether on a larger scale, all adults are responsible for all children.

Case study: Darren, Bedfordshire

It's a difficult situation when someone is a victim of what appears to be mindless violence. I myself have intervened in a situation where a group of teenagers walked through a pub, where I was having a quiet drink with a friend, walked straight up to another teenager threw him to the floor and started kicking him in the head.

At first I was shocked by what I was seeing, but once I realised what was happening I ran into the group and pulled the main attacker.

Thinking about it afterwards I could have actually got involved in a fight and seriously injured someone or myself, then I would have to give account of my actions to the police or at worst ended up in hospital.

Would I do something like this again? It would depend on the circumstances of what is happening and who is the victim.

So what about the "bystander effect"?

Evolutionary biology suggests our natural genetic instinct, external is to behave in an altruistic and supportive way if someone is being attacked. So why do people seem to walk by, particularly if they are in a crowd?

Psychologists suggest three reasons. One is "audience inhibition", which makes us fear that taking action will be viewed negatively by the other people.

The second is "social influence", which leads us to assume that if no-one else is helping, there is no need to do anything.

And the third, most important, reason is "diffusion of responsibility", which encourages us to take the view that if no-one else is doing anything then why should we.

An experiment was carried out with an actor pretending to be ill. Most people ignored him until one went to his aid - which encouraged others to help

Dr Lasana T Harris, an experimental psychologist from UCL, set up a demonstration with an actor, who was clutching his stomach and moaning, to illustrate the bystander effect.

Seeing a middle-aged man on the pavement, in evident pain and distress should signal to passers-by this is a "help" situation. But Dr Harris' research suggests that the larger the crowd, the more likely it is that people will ignore the situation. However, once one person stops, others follow suit.

But the much-cited bystander effect - the name psychologists have given to the group mentality that leads to people watching a crime effectively ignoring it - may only hold true when the situation is not a dire emergency.

If the emergency is more immediate - such as an explosion - the experience quickly bonds a group and "builds a sense of shared identity", meaning people are more likely to help one other.

Prof Levine has also found that the bystander effect disappears as soon as someone takes action. The first person to help tends then to be a model for others to imitate.

A crowd of people lifted a bus off a trapped man

This could be seen when a crowd acted in unison to free a man trapped under a London bus in 2015.

People had started to try to move the bus, which made it easier for other bystanders to join, Prof Levine says. It was obvious that their help was required to move the bus, making their internal calculations easier.

"The thing is, we hear about occasions when people don't help and we're outraged, or we hear about when they do help and something goes horribly wrong.

"But if you fell over in the street, someone would come and help you up. We just don't hear about these lower-level interventions.

"Most of us really are good Samaritans."

- Published20 June 2016

- Published23 January 2015

- Published12 September 2012