What will Brexit mean for iconic British food?

- Published

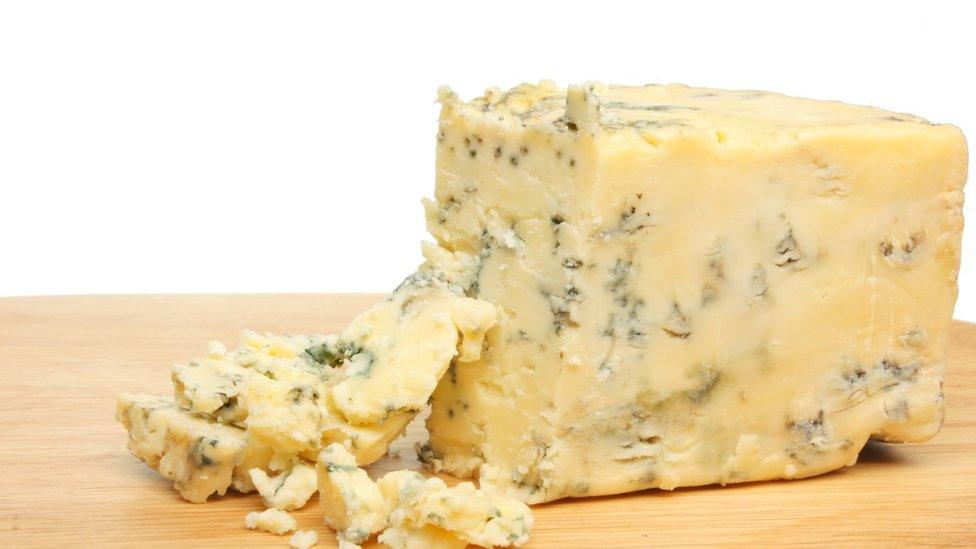

Under current EU law Stilton can only be produced in Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, and has to be made with pasteurised milk

Cheddar cheese, Melton Mowbray pork pies, a pint of traditional scrumpy - all foodstuffs that speak of British traditions and are exported across the world. But are businesses behind some of the UK's finest produce worried about the impact of Brexit on their delicacies?

Richard Clothier's family business is nestled in idyllic Somerset countryside but, like much of the country, things are not so tranquil down on the farm.

As the fall-out from the EU referendum continues, he and his brother Tom are anxiously examining the ramifications of the vote.

Their business is the biggest exporter of Cheddar cheese to France and now Richard is looking for positive signs in a volatile marketplace.

While admitting he was "shocked" by the results, he now plans to hold the Brexiteers to their word and ensure trade is not affected.

"I think what we need now is a period of political stability - we don't need any infighting," he said.

"There's a lot of work to do. Everyone needs to work together because there are some really important challenges coming up for all of us."

Richard Clothier worries how the UK's exit from the EU could affect trade with important customers on the continent

Worried

The same concerns are shared by Matthew O'Callaghan, chairman of the Melton Mowbray Pork Pie Association, a body protecting the interests of the famous East Midlands pastries.

He also leads the UK Protected Food Names Association, which includes local delicacies such as Arbroath Smokies, East Kent Golding hops, Stilton cheese and Pembrokeshire Early potatoes that are given special status to preserve traditional or specialist methods.

Protected Food Names

Under EU law there are several ways to protect the heritage of famous foods made traditionally or tied to particular locations

Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG) means the recipe or method of production has to be very specific

Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) means the recipe or method is protected and it has to be carried out in a specific location

Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status means it also has to be made with ingredients from a certain geographical area

Examples include Parmesan Reggiano cheese, Parma ham, Stornoway black pudding and Champagne

However, the legislation protecting these foods comes from the EU's Protected Foods Name Scheme,, external which he fears could be forgotten about in the post-EU political upheaval.

"We have some very worried members, and there's a lot of concern about what happens now," said Matthew.

"You don't have to be a member of the EU to be protected - for example, Colombian coffee is protected - but it has to be a reciprocal arrangement. They protect our products if we protect theirs.

"We will need specific legislation to protect iconic products in the UK and if we want to protect them in the EU, and my fear is that it's going to get lost in everything else that's being discussed."

Unsurprisingly, producers of specially protected food and drink are worried that leaving the EU could make it easier for others to make cheaper versions of cherished cuisine.

Philip Cranston is one of 20 butchers allowed to make genuine Cumberland sausage, which has been protected since 2011.

He said he expects the UK government to carry out similar protections to stop imitators.

"I'd be shocked if it was let go and the process to produce the traditional sausage was opened up for everyone to make," he said.

Foods with Protected Designation of Origin

Cumberland sausage has a distinctive shape and flavour

'Impossible to recruit'

Adrian Barlow, chief executive of English Apples and Pears, said losing migrant workers from the EU would harm heritage fruit producers, as well as larger scale orchards.

"Apples and pears are harvested by hand and seasonal workers are required for this," he said.

"Despite enormous efforts by growers, government departments and job centres, it has proved impossible to recruit from the UK any more than a small proportion of the numbers necessary. In short, the British are not prepared to undertake this type of work. Consequently, almost all seasonal workers are from abroad, and at present, mainly from eastern Europe.

"The UK apples and pears sector requires about 12,000 seasonal workers per annum. Unless they can be recruited from abroad, many growers will be forced to cease production which will damage local businesses, local economies, the national economy and deprive consumers."

Matthew O'Callaghan agrees, and thinks the loss of food name protection could see much-loved foods disappear or be replaced by inauthentic replicas.

"It protects jobs, it protects crafts and it benefits the public," he said.

"If the legislation disappeared I think we would get imitations, we would get cheaper products, and they would lose their links with their places of origin."

The future of fruit growing in the UK faces uncertainty, according to the chief executive of English Apples and Pears

A spokesman for the Department for Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) said any changes from Brexit would not come in immediately, and discussions would need to be held about any new protections.

Like in many areas of post Brexit life in the UK, the question of what happens next does not look like it will be answered any time soon.

For people like Richard Clothier, though, there are bills to pay and time is of the essence.

"Disruption in trade just isn't an option for us."