Rise in lone children seeking asylum in England

- Published

Bilal came to the UK as a 15-year-old asylum seeker

The number of asylum seeking children in the care of English councils has risen 62% in a year.

The largest group are boys aged 16 and 17, coming from countries such as Afghanistan or Eritrea.

A refugee charity says many children are facing "serious shortages" in legal advice to help them make their case to stay.

The Home Office said it had increased funding to cover the costs of care and other support for unaccompanied minors.

Figures released to the BBC England data unit under the Freedom of Information Act reveal at least 104 councils were caring for more unaccompanied minors than they were in 2015.

There were at least 4,156 children seeking asylum without parents or guardians and cared for by 147 councils on 31 March 2016, compared with 2,569 the year before. The figure is likely to be higher as some councils did not have up to date figures and some would only say they had fewer than five such children.

The BBC's findings coincide with a report by the children's charity, Unicef, which has called on the government to do more to help unaccompanied children driven from their homes by conflict.

Unaccompanied minors made up about 8% of all asylum claims in the UK in 2015.

For more stories from the BBC England data unit follow our Pinterest board, external.

Bilal was cared for from the age of 15

'Every single minute I missed my family'

Bilal is 22 years old and is now a passionate Leicester City supporter. He arrived from Afghanistan as an unaccompanied child, aged 15. The police handed him over to social services in Warwickshire.

"Every single minute I was missing my family," Bilal said.

"I tried to make myself busy with football, games, making friends.

"My English family tried to make me happy. When I tried to cry, they'd take me to the playground or to football.

"Before I'd cry, I'd try to busy myself. It was not easy."

He was initially fostered by an English family, then moved to Leicester, where he went to secondary school, and he still lives in the city. He is in the process of applying to settle in the UK permanently.

Yet he urges other refugees to think carefully about the journey.

"We were in a small boat for 10 to 15 people," he recalled. "It took three or four hours to Greece. It was massive water. If someone was coming now I'd tell them 'stop, it's not easy'. So many people are dying."

Bilal said Leicester was now his home.

"If I go anywhere I say I'm from Leicester, originally from Afghanistan."

The data shows Kent County Council, which includes the Port of Dover, now cares for more than one in five of England's unaccompanied minors.

It is followed by Croydon, which is where the UK's asylum screening unit is based and where asylum seekers must present themselves if they have already reached the UK.

Others in the top 10 include Northamptonshire.

A spokesman for its county council said: "Geographically, it is often the first place that lorries stop to take a break after coming in from the ports and there are a large number of lorry stops, the M1, A45 and A43 as well as warehouses and logistics companies."

Duty of care to young adults

When a child claims asylum in the UK they become the legal responsibility of the local authority in which they are discovered. Local authorities receive funding from the Home Office to look after these children and they are usually either placed into foster care or "semi-independent living" situations.

Councils' responsibility to looked after children does not end when they turn 18.

In Northamptonshire, there were 147 children 17 and under seeking asylum. However it was also working with a further 94 care leavers aged up to 24.

A spokesman for Northamptonshire County Council said there was often a shortfall between the government grant it receives and the costs.

The Refugee Council said there were "serious shortages" in legal advice for asylum seeking children

Judith Dennis, policy manager for the Refugee Council, said the UK received about 3% of asylum claims made by unaccompanied children in Europe.

"Around the world, more lone children than ever before have been forced to flee their countries," she said.

"These children arrive without their parents or guardians and have escaped countries where conflict, violence, or human rights abuses are rife.

"It's often a child's parents, not the child themselves, who take the decision that the situation is so dangerous that the child must be sent to safety."

Ms Dennis said there were "serious shortages" in the availability of legal advice for children trying to navigate the asylum system.

The largest group of unaccompanied children are 17-year-old boys. And some are not believed by the authorities to be as young as they claim.

Bristol City Council, for example, gave details of two "children" aged 18 and 19, who were being cared for while "appealing age assessments".

Ms Dennis said: "One of the biggest issues young people seeking asylum face on arrival in the UK is that they are usually unable to verify their date of birth with official documents. Most countries from which refugees come don't register births in the same way as in this country, although some will have documents that can help provide information about age.

"Refugees may have to travel on documents that do not belong to them or have been obtained fraudulently; this is accepted in international law in recognition that people may not be able to obtain passports or travel documents from a government from which they are escaping.

"Such documents are likely to have an adult's date of birth because children would not be allowed to travel alone."

The number of people displaced by conflict was at the highest level ever recorded, the UN refugee agency said. About one in every 113 people on the planet were refugees, asylum seekers or displaced, half of them under 18 years old.

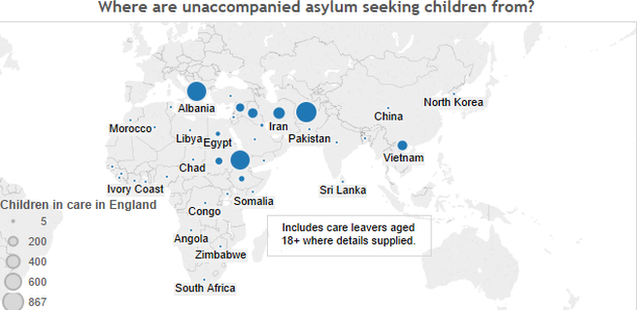

Countries of origin

Afghanistan and Eritrea, which has been criticised for human rights abuses, account for the largest numbers of unaccompanied children cared for across England.

There were 148 unaccompanied Syrian children in the care of local authorities. These were not part of the relocation scheme for vulnerable Syrians fleeing the civil war.

And there have been instances of lone children coming from Russia, North Korea and Cuba.

For an interactive map breaking down asylum-seeking children by country of origin click here, external.

Get the data here, external.

'Squalid trade'

From 1 July 2016, councils were no longer expected to look after more unaccompanied asylum seeking or refugee children than 0.07% of the general child population in their area. If the figure was exceeded they are now to transfer a child to another local authority.

Experts on migration are waiting to see what the impact is of distributing children more evenly across the country.

Dr Nando Sigona, of the School of Social Policy at the University of Birmingham, said: "A better distribution of unaccompanied asylum seeking minors across local authorities may sound like a sensible idea - but if it really is will depend on what criteria will be applied to guide the redistribution."

And Alp Mehmet, vice-chairman of Migration Watch UK, said: "While we welcome the huge efforts being made to help the most vulnerable, it is also important that in so doing there is no encouragement of people traffickers to ply their squalid trade and young people to risk their lives to get to the UK in the belief that once here their future is assured."

Peter Oakford, Kent County Council's cabinet member for specialist children's services, said the authority faced "enormous pressures" on services, foster placements, accommodation and finances.

"We believe that any national dispersal scheme should be mandatory," he said.

"We urge all local authorities to accept their responsibilities under this new system. We urgently need to share the numbers fairly across all local authorities.

The Home Office said children's safety and welfare was "at the heart of every decision made".

"That is why we have substantially increased funding to local authorities who are responsible for supporting unaccompanied asylum seeking children," a spokesman said.

"We are keen to ensure that no local authority is asked to take more [children] than the local structures are able to cope with."

From 1 July 2016, the daily rates paid to councils went up from £95 to £114 for under 16s and from £71 to £91 for 16 and 17-year-olds.

- Published30 August 2016

- Published20 August 2015

- Published4 February 2016

- Published4 March 2016