Did the 1966 World Cup change England?

- Published

England fans celebrated winning the World Cup in the fountains at Trafalgar Square, London

England's victory in the 1966 World Cup is now a part of the national legend - an almost mythical time when the nation's footballers could rightly claim to be the world's best. But the England of the 1960s was quite a different place from today. How did it change the country and what was it like to live through it?

Times were changing in England. There was the pill, Twiggy and the swinging music scene, but it was also only two decades since the end of World War Two. Many people had been through National Service and the country was also adapting to increased immigration.

The BBC did not launch colour television until the year after the tournament and some households would not have even owned a black and white set on which to watch matches.

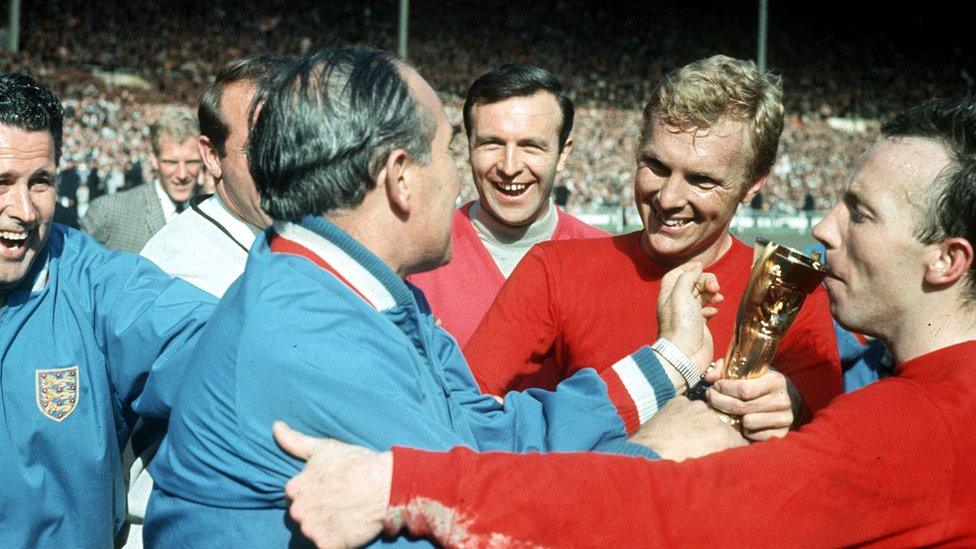

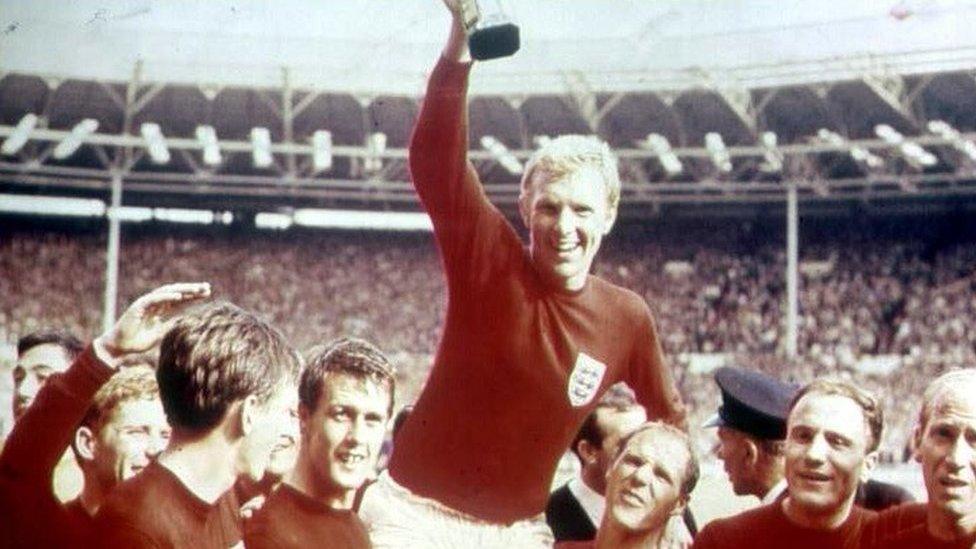

Football was overwhelmingly a working class game on and off the field. Some club players travelled to games on the bus or Tube or took summer jobs during the close season. England captain Bobby Moore was at one stage, according to his wife Tina, paid just £8 a week by his club West Ham United.

England players could walk down the street unchallenged and when the tournament had finished, some of the new world champions drove home from London with their wives in modest family cars.

It was a more innocent time for football, before the 1970s ushered in hooliganism and million-pound transfer fees.

What was England like in 1966?

The tournament took place between 11 and 30 July. While it is easy 50 years on to assume the nation must have been gripped with football fever during the World Cup, the tournament was in fact "a slow burner", according to Dil Porter, emeritus professor of sports history and culture at De Montfort University in Leicester.

He said the English public had been falling out of love with football, with attendances and interest declining through the 1950s and early 1960s and sport not getting as much media coverage as it does now.

"I don't think there was a lot of flag waving until the quarter-final and semi-final stage," he said. "People not normally interested in football were then getting interested."

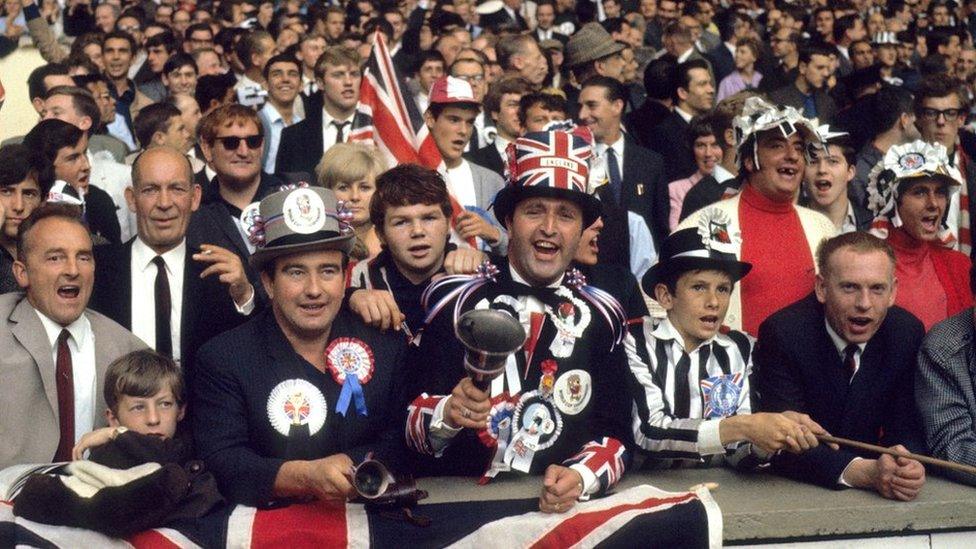

More fans at matches wore suits than replica shirts - and union jacks were the flag of choice rather than the St George's cross

A merchandising team did their best to stoke up interest in the tournament

The opening match of the tournament was between England and Uruguay. BBC football commentator John Motson remembers: "You could walk up to Wembley and buy a ticket on the night. So that's how long it took for the World Cup to grip people's imagination."

However, while in London there was little sign of the hysteria which would be evident later that month, in footballing hotbeds such as Liverpool, excitement was high.

"This is the football city of England - not stiff and serious London where you can hardly tell there is a World Cup competition going on," reported Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter in its coverage of games at Everton's Goodison Park stadium.

"I don't think I have ever heard a football crowd enjoy themselves as they did in last night's game between Brazil and Bulgaria," the paper's correspondent wrote.

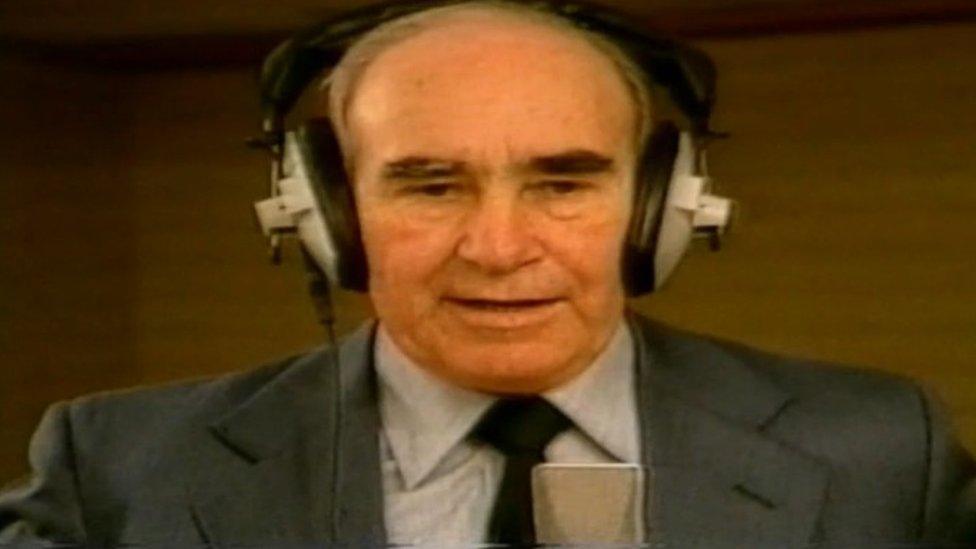

David Coleman explained how the World Cup was proving popular

There was something approaching a carnival atmosphere with the streets around the ground decorated with hanging baskets and bunting.

Kenny Leary, whose mother lived in Claudia Street, one of the terraced roads near the ground, said decorating it had been a tradition since VE Day.

"The streets around Goodison Park were all decorated and it became like the United Nations round there as fans from different countries came to look at the streets," he said.

"I watched the final at the house in Claudia Street and it was a fabulous experience."

Irene Hughes and other residents of Claudia Street add the finishing touches to their decorations in preparation for the match between Bulgaria and Brazil at nearby Goodison Park

The Brazilians, the reigning world champions, played their games at the ground. They were the star attraction for many fans, especially those who got to meet them at their base in the Lymm Hotel in Cheshire.

"My granddad never stopped talking about meeting Pele," said current hotel manager Jamie McDonald.

"The players were very approachable, some even borrowed bikes to go round the village."

Glenda Bowers, who was 15 at the time, recalled: "My friend and I hung round outside all the time. We got loads of autographs of the Brazilian team. I must have had Pele's a dozen times. I think when I got married my mum threw them out!"

The legendary star left behind many treasured memories. Alan Williams, who organised a recent exhibition in the village said: "A press photographer wanted to photograph Pele throwing something to the laundryman.

"So he threw his training kit, which he allowed him [the laundryman] to keep."

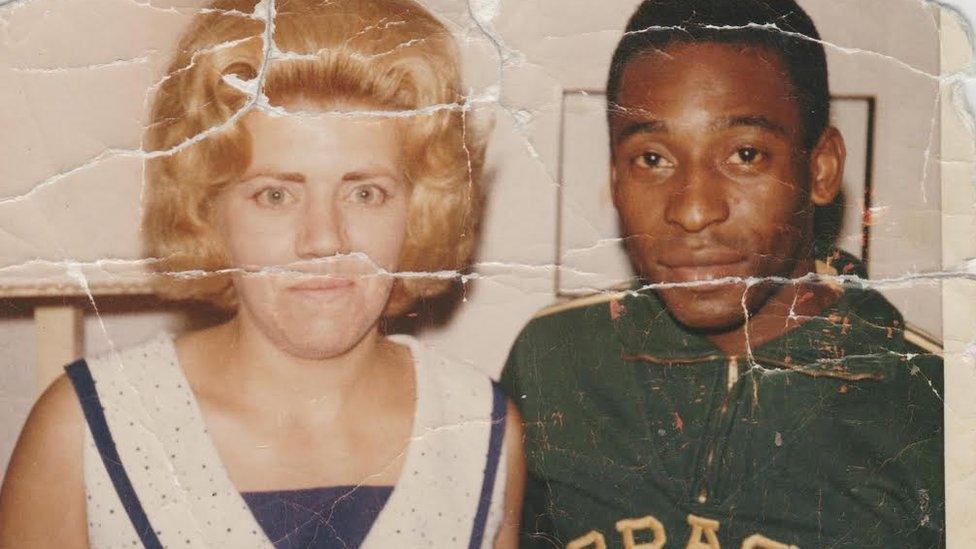

Barmaid Bessie Vale has kept a photo of herself with Pele in her purse ever since. And Lymm certainly lamented the team's early departure from the tournament. The Manchester Evening News reported schoolgirls crying in the streets, begging certain members of the team to stay as they left the village.

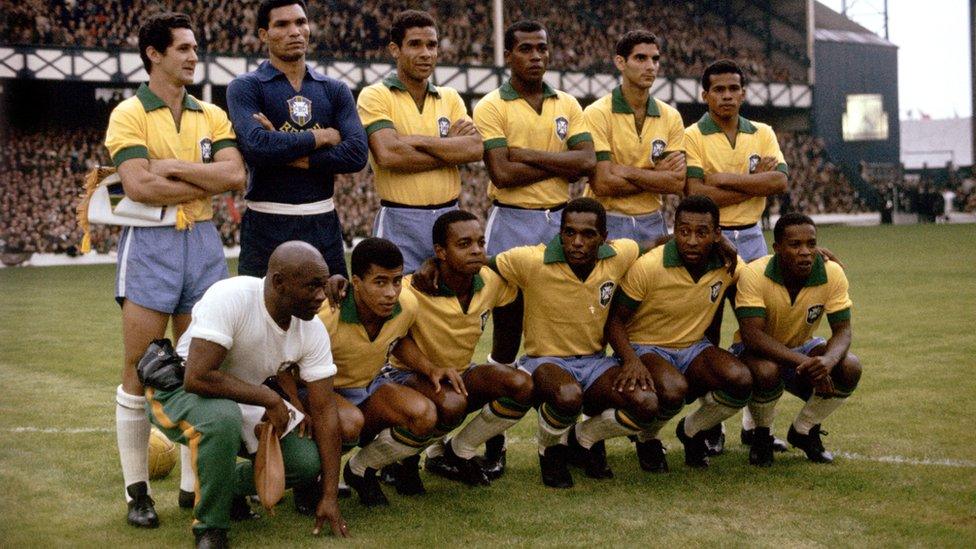

Black professional footballers were almost unheard of in the UK, yet the reigning world champions were a largely black team, led by their superstar Pele. Four miles from Goodison Park, in the Toxteth district, this had an electrifying impact on the city's Afro-Caribbean community.

Brazil - champions at both the previous two World Cups - had a number of brilliant black players in their team

Barmaid Bessie Vale has kept this photo of her with Pele in her purse ever since Brazil stayed at the Lymm Hotel

It was less than two decades since the beginning of substantial migration from the Caribbean to the UK and migrants still faced exclusion from many sections of society, including football.

"To be honest we were cheering for Brazil, there weren't that many black role models in football so it had to be Brazil," said Wally Brown, an engineer who would later become a community leader in Toxteth.

He was also lucky enough to get a ticket for Portugal's famous 5-3 victory over North Korea in which Portugal's Eusebio, who was born in Mozambique, bagged four goals.

"The Portugal game was the first time I had been at the ground when there was a black player, it was an incredible atmosphere," added Mr Brown.

"In the old First Division there was Clyde Best at West Ham or Albert Johanneson at Leeds but I never used to go to Goodison Park when there were teams with black players because the atmosphere was so bad."

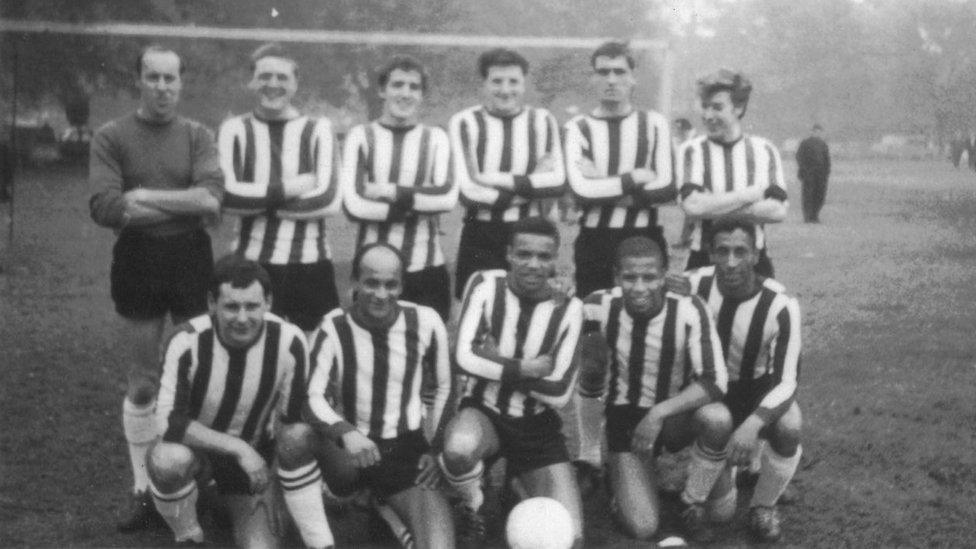

Wally Brown (centre, bottom row) was inspired by Brazil's black superstars

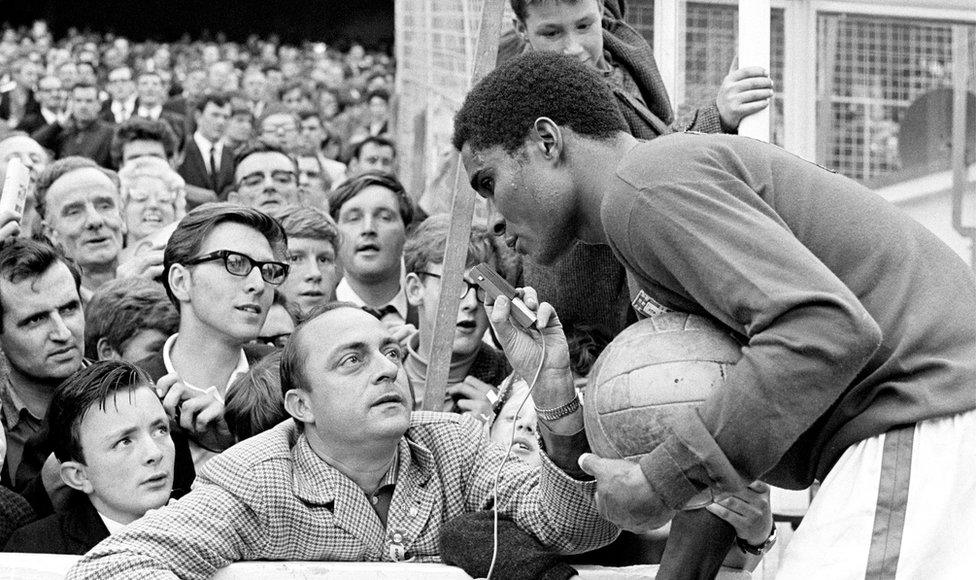

Portugal's Eusebio - giving an impromptu pitchside interview at the game against North Korea, in which he scored four goals - was the tournament's top scorer and, like Pele, an inspiration for some black football fans

Black players would break through into the top levels of the professional game over the next decade. Brendon Batson, who went on to star for West Bromwich Albion in the late 1970s, was a 13-year-old growing up in Walthamstow, east London, when the World Cup began.

He said black people he knew at the time had "no interest in football whatsoever".

"The families I met were predominantly Jamaican... it wasn't on their radar," he said.

"That first wave were trying to make their way and worked very, very hard. Lots of kids (were pointing) towards apprenticeships, including in the motor trade."

World Cup 66 Live

Join the BBC to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of England's historic World Cup win on Saturday 30 July.

This live event will unfold in real time at The SSE Arena, Wembley in front of an audience of 10,000, and will be broadcast live on BBC Radio 2, BBC Red Button and in cinemas across the UK.

Read more: World Cup 66 Live

Batson himself was born in Grenada, moved to England aged nine and then got into football playing with friends "during school, after school" while being "the only black lad in my class for a long time".

But he said the likes of Pele and Eusebio were a "big inspiration" for young British black players like himself to emulate.

"Around the time there was also Cassius Clay (boxer Muhammad Ali)," he added. "You suddenly see black sporting superstars."

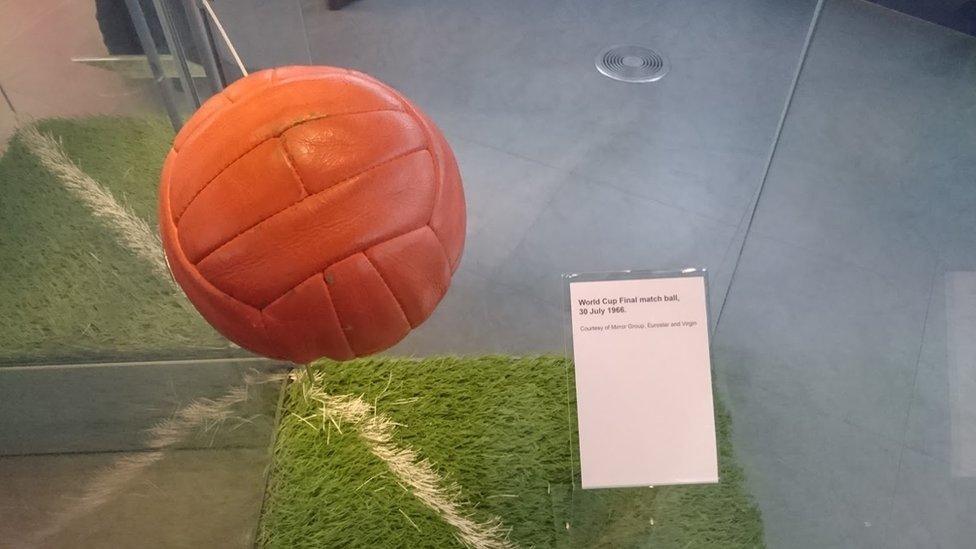

Nearly all the teams wore kits made by Umbro - in a factory in Congleton, Cheshire

And the footballs were made at the Slazenger factory in Wakefield, West Yorkshire

While Brazil's blend of superstars were capturing the imagination in Merseyside, in the North East an even more exotic team were winning fans - North Korea.

They were the underdogs, played all three group games at Ayresome Park - including a shock 1-0 victory over Italy - and, like Middlesbrough, wore red shirts.

It was the height of the Cold War and the country's communist regime ensured their team did not mingle much with local people. However, despite this, Teessiders took the players "to their hearts", said Keith Belton, then a 27-year-old trainee architect from Newton Aycliffe.

"North Korea was the most exciting thing about the World Cup being in the North East, the other games were not that thrilling but North Korea did far better than expected," he said.

"The community liked them but it was very difficult because none of them spoke any English and North Korea was a politically sensitive place to come from," said Bernard Gent, a press officer for the FA during the tournament.

"They weren't wandering like some teams might have done, round the town and round the shops, there was a lot of security around them."

At the height of the Cold War, the USSR took on North Korea in Middlesbrough

The North Koreans may have been kept under heavy security but a British sailor was able to celebrate with goalscorer Pak Seung Zin after the 1-1 draw with Chile at Ayresome Park

However, some interactions did take place, including with a boy, Tony, who was having his haircut when members of the squad came in for a trim.

"I remember they were really small," he recalled later. "The craze at the time was Batman and I had a T-shirt on, and they started picking me up saying 'Batman! Batman!'"

Graham Fordy, the former commercial director of Middlesbrough FC, does remember seeing the North Koreans on one trip into town.

"It was a whole new world for them, a place where they could do what they wanted and behave as they wished. It was like Disneyland for them compared to the country they came from. A country where you could say what you want must have been quite remarkable."

Try your hand at a 1966 World Cup quiz or spot the ball challenge, from CBBC

The North Koreans were not the only foreign footballers kicking about in the North East during the World Cup. John Phelan was 15 and, with his mother, got the bus from Crook to see the games played at Roker Park.

"We were walking near the stadium and this man passed us, I said 'that's [Hungarian legend] Ferenc Puskas'," he said.

"By the time I got a pencil and paper out to get his autograph he had gone, but still, to see someone like that in Sunderland was amazing."

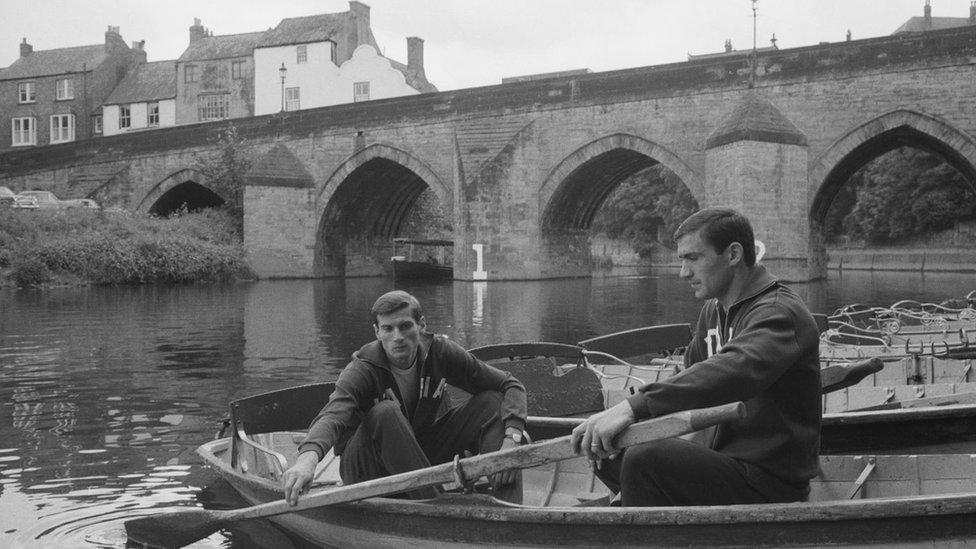

Italy were knocked out in the group stages but were around long enough for some social activities in the North East. Giacinto Facchetti and Tarcisio Burgnich relaxed by taking a boat out on the River Wear in Durham

Uruguay also enjoyed some downtime - entertained and intrigued by a local accordion player as they waited to board the team coach in Sheffield

Of course one of the teams who fared well in the tournament were West Germany, perhaps inevitably being pitched against England in the final.

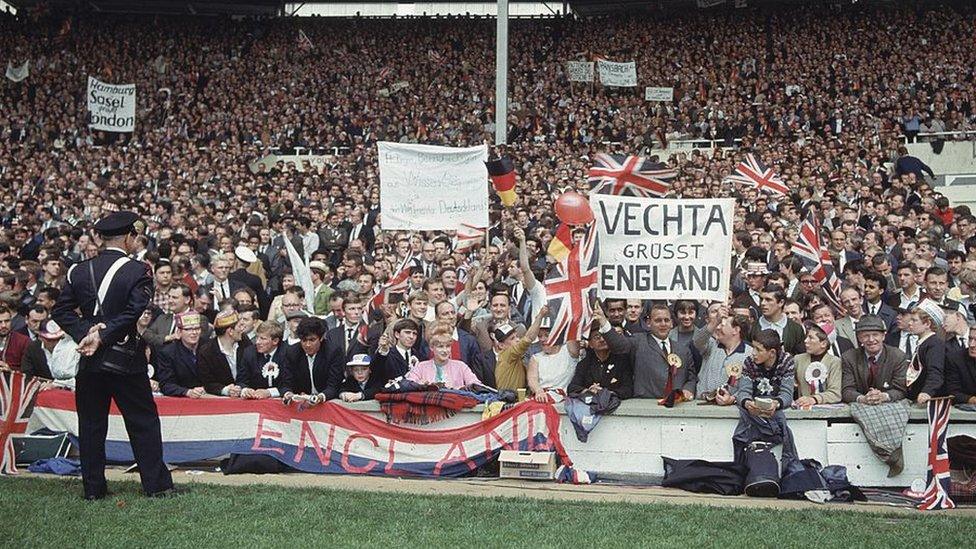

With thousands of German fans attending matches, the tournament would have been the first time many English people had encountered anyone from the country since the war.

A fan at the final, John McCartney, had two uncles who served at Dunkirk and said people were "quite rude" behind Germans' backs but there was no hooliganism.

Mr McCartney, then 22, said: "We still hated the Germans but... I think you had respect for each other."

Prof Porter also said examples of open anti-German sentiment were "few and far between" and England fans and Germans were "mixing happily and swapping beer".

"There were some complaints in the German press about some aspects of British press coverage," he said. "'The German team advance on London' - (there were) a lot of military metaphors.

"But compared with the 1990s, 'Achtung! Surrender!' in the Daily Mirror at the time of Euro 96, it's all very mild."

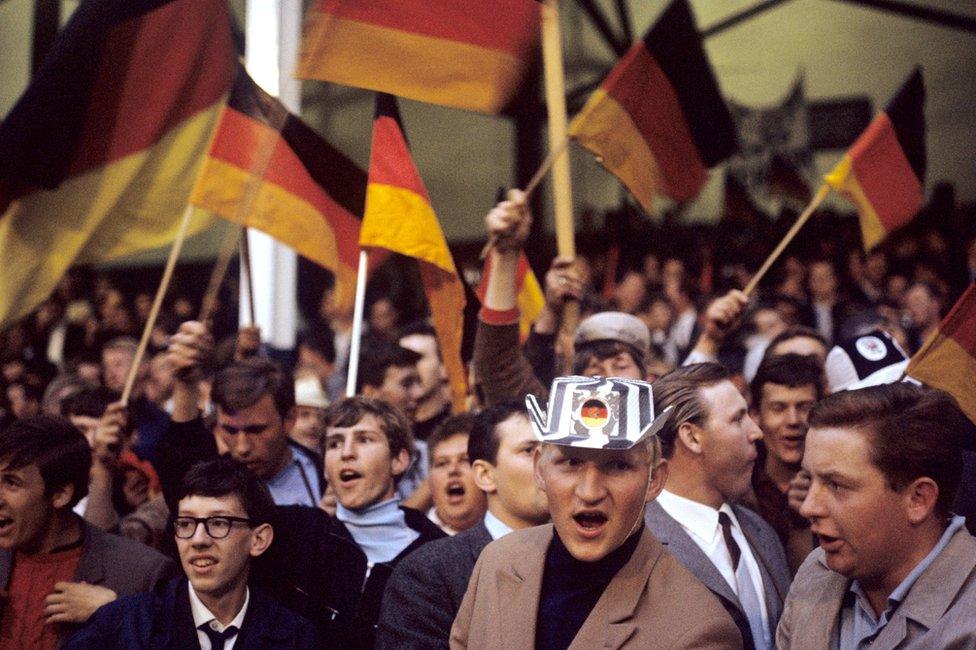

Thousands of German fans travelled to England and, even though it was only two decades since WW2, were mainly welcomed

The World Cup gave locals the chance to mingle with visitors from around the world. Seventeen-year-old Kathleen Riddel, from Sunderland, joined some Italians to cheer on their team against the USSR at Roker Park

The West German squad based themselves in the Derbyshire market town of Ashbourne - and the current mayor Caroline Cooper remembers the team mixing with the locals.

She said the older residents of Ashbourne "just saw them as people".

"They went back to their normal lives [after the war]. They didn't mix the war with the German football team."

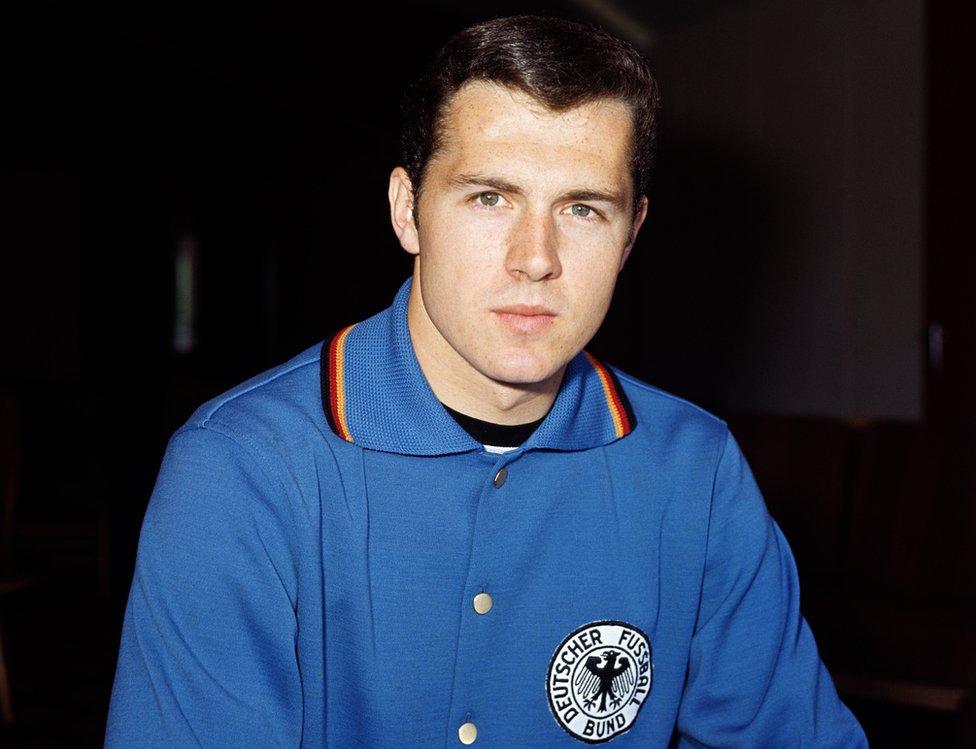

Working as a 15-year-old Saturday girl in a shop, she herself met one of the star West German players.

"Franz Beckenbauer asked me 'have you got any black bread?'," she remembers.

"I, not being very worldly at that time... said 'I'm sorry, the best thing I can do is Hovis' - but he bought some anyway."

Franz Beckenbauer wanted black bread but made do with Hovis. It didn't prevent him becoming one of the world's greatest players

Another young woman who the tournament left a lasting impact on was Sue Lopez.

"I had always been a football fan since my mum took me to see the local village team. My granddad and uncle had taken me to The Dell to see Southampton," she said.

"I got the chance to see France v Uruguay at White City and I will never forget it. Here I was watching the World Cup - it was incredible. I had only been used to crowds of around 7,000 at the Dell. I just wanted to be part of it."

Inspired, she saw an advert for a women's team and joined up.

"They told me to play full back but I ran down the wing and scored a goal," she recalled.

She went on to play for Southampton's women's team and became one of the most prominent women football players in the 1970s, winning 22 England caps and spending one year playing for Italian side Roma.

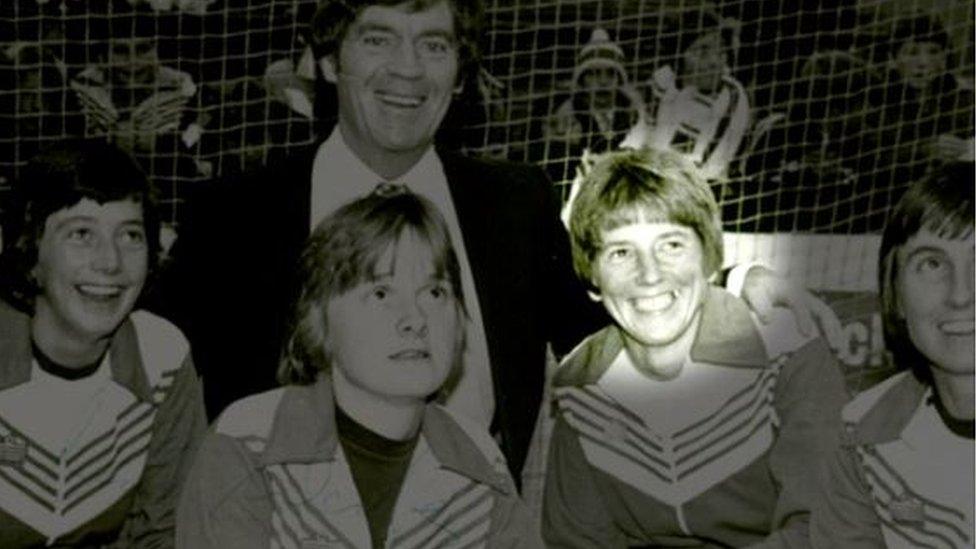

Sue Lopez, pictured here with former Southampton manager Lawrie McMenemy, played for England 22 times

England's route to the final saw them win their qualifying group and then defeat Argentina 1-0 in the quarter finals, before beating Eusebio's Portugal with two goals from Bobby Charlton.

Whereas at the start of the tournament tickets for England games were still up for grabs, by now, with Alf Ramsey's men on the brink of immortality, the nation was gripped by hysteria.

On the day of the final against West Germany, as people soaked up the marathon coverage from midday, Keith Leadbitter was preparing for his first driving lesson in Southsea.

"I did not see another vehicle for the entire 30 minutes," he said. "It was quite handy actually as after less than one minute I was asked 'which side of the road do we drive in England?' I had strayed over the white line somewhat."

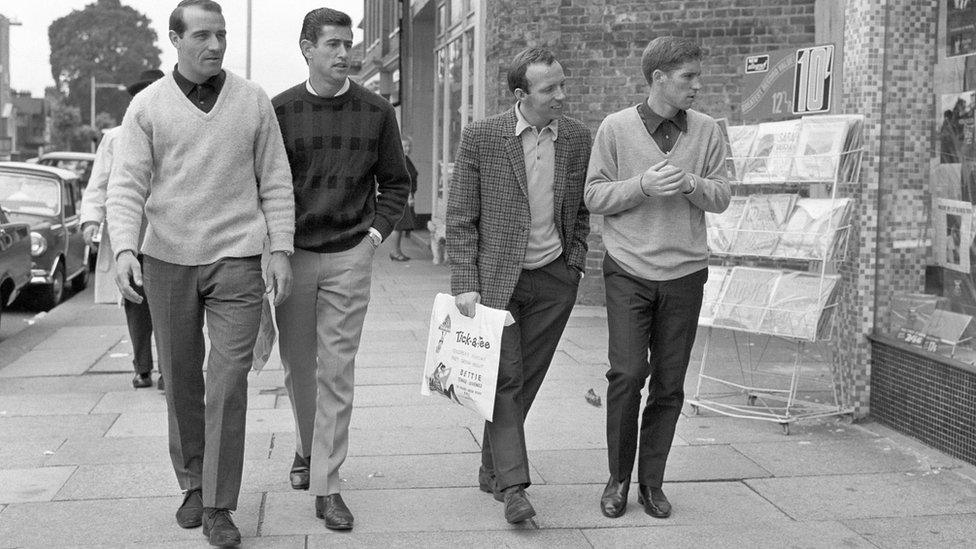

England players were free to nip out on a shopping trip - untroubled by fans - the day after winning the semi-final

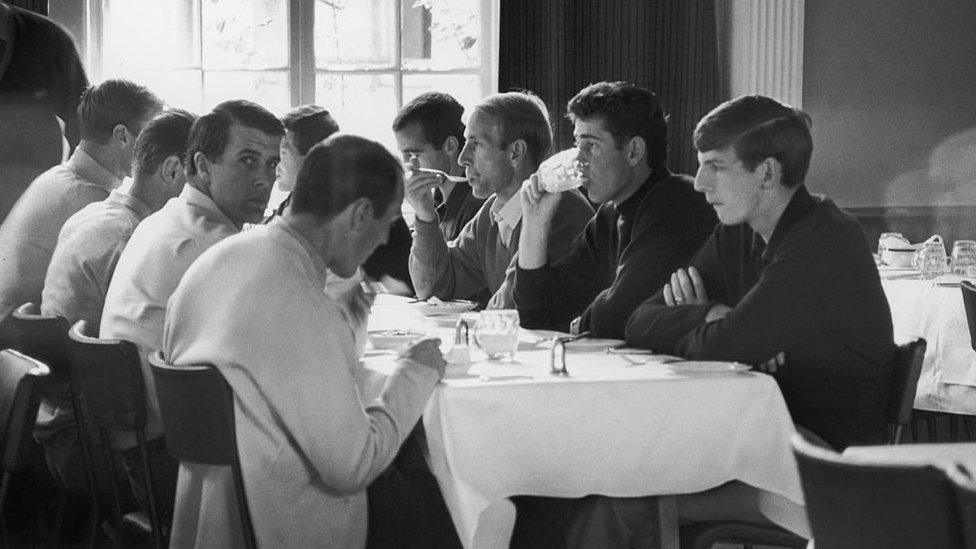

And press photographers were allowed in to snap the England team eating their dinner the day before the World Cup final - which would surely be unthinkable today

Across the country, it was the same story - the streets were deserted as the nation watched and hoped.

West Germany took the lead before England equalised minutes later through Geoff Hurst and the sides went in level at half time.

John McCartney, who had dashed to the game from his job at a bank, was behind the goal in his work suit when England went 2-1 up through Martin Peters.

"I was standing next to someone I didn't even know from Liverpool and we were hugging each other... and we were best of mates by the end," he said.

Minutes before full time, however, the Germans equalised, plunging the game into extra time. England scored again through Hurst's controversial "over the line" goal and, as the same player ran in for his hat-trick, fans ran on to the pitch, prompting commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme's famous words: "Some people are on the pitch. They think it's all over. It is now."

There was little segregation between the England and West Germany fans at the final

Mike Richardson, who had been at the tunnel end, was one of them.

"I saw other people making moves to go on the pitch, then I saw other people running on," he told author Matt Eastley in his book 66 on '66.

"I was so excited by what was happening. I jumped over the fence and ran on celebrating victory."

Then aged 17 and from Clapton, east London, Mr Richardson was an aspiring pop star who had a gig that night in Shaftesbury Avenue where the atmosphere inside the club "was sensational".

"I remember walking through Piccadilly Circus where everyone was partying," he said. "It was a fantastic night, the best night of my life I would say."

England's third goal did cross the line, honest

Of course most people watched the game at home on television. Eight-year-old John Cross, from Blackpool, had watched the game huddled round a small black and white television with his mum and dad and four siblings.

"I remember feeling so excited. Not only had we won the World Cup but the man-of-the-match Alan Ball was a Blackpool player," he said.

"After the match I ran out into the street and everybody was playing football trying to relive the game."

England's triumph was masterminded by Alf Ramsey, helped by his on-field leader captain Bobby Moore

Not everyone was entirely glued to the TV, though. In Mark Perryman's book 1966 and Not All That, Gary Messer remembers a thunderstorm as extra time approached.

"Mum insisted on the TV being turned off and the aerial unplugged (given that lightning would strike one house out of millions in south London)," he said.

"We listened to the only World Cup England are ever likely to win on a dodgy transistor radio."

Fifty years later, the England of the 1960s now seems a very different place - as distant as the country's chances of winning another world cup, perhaps.

But apart from the victory, one reason the tournament is remembered fondly is it took place in "less complicated times," according to Prof Porter.

"The English players of 1966 are routinely portrayed and routinely portray themselves as authentic working-class heroes, world champions who were happy to eat modest meals in motorway service stations... after winning the trophy.

"Wembley 1966, as remembered by many English people... belonged to a world that they had lost, a more innocent world before hooliganism and Heysel... when rival fans exchanged banter rather than kicks."

Credits

Reporting: Andrew Dawkins, Paul Burnell, Duncan Leatherdale, Neil Heath

Editors: Dave Green and James Clarke

- Published12 July 2016

- Published11 July 2016

- Published25 June 2016

- Published10 June 2016

- Published4 June 2016