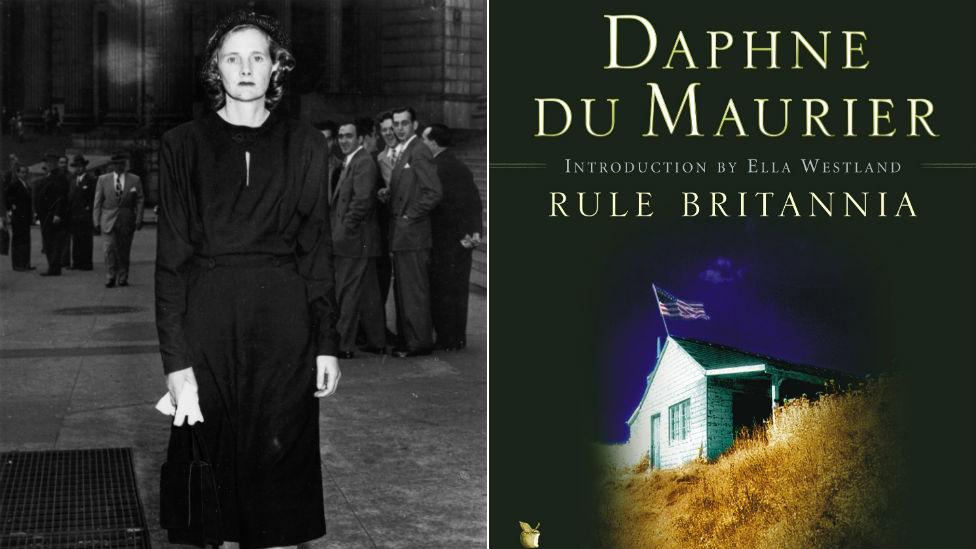

Did Daphne du Maurier predict Brexit?

- Published

British novelist Daphne du Maurier anticipated the British referendum in her 1972 book Rule Britannia

Breaking apart from Europe, resentment towards Westminster elites, financial uncertainty - sound familiar? Back in 1972, before the UK had even joined the Common Market, Daphne du Maurier had anticipated it all in her novel Rule Britannia. So how much did she get right?

Du Maurier's novel imagines a future UK facing severe economic instability after joining and then leaving the EU's predecessor, the Common Market.

The electorate has voted to leave in a referendum and the government has instead formed a new union with the United States.

However, when the marines arrive on English soil, it begins to look like an invasion.

Du Maurier was writing after the 1970 general election had brought Edward Heath's Conservative government to power, promising to take the UK into the Common Market.

Though the referendum does not take centre stage in Rule Britannia - acting rather as the context for the US occupation - the text is laced with references to the political events and public attitudes surrounding the vote.

Rule Britannia was Du Maurier's last novel

In Du Maurier's imagined referendum the government has "backtracked" on its original support for the Common Market and now opposes British membership.

If this contrasts with the Conservative government's support for the Remain campaign this year, the book still has clear parallels with political events, according to Professor Helen Taylor, of Exeter University.

She cites one section of the novel, in which the prime minister bemoans the political and financial repercussions of the leave vote, saying it "brought great economic difficulties, as I feared would be the case and as I warned you at the time, and our political autonomy and military supremacy were also endangered".

"That sounds exactly like [David] Cameron," Prof Taylor suggests.

So what else may Du Maurier have got right?

The road to Brexit

Prof Taylor said there were similarities between the rhetoric of David Cameron and the fictional prime minster in the novel

1961 - Britain applies to join the European Economic Community (EEC), also known as the Common Market

1963 - French President Charles de Gaulle vetoes British membership

1970 - The Conservative Party under Edward Heath wins the general election, having promising to take the UK into the EEC

1972 - Du Maurier's Rule Britannia is published

1973 - Britain joins the EEC

1975 - The UK votes to stay in the EEC in a referendum called by Prime Minister Harold Wilson

2013 - Prime Minister David Cameron promises a referendum on British membership of what is now the European Union (EU)

2016 - Britain votes to leave the EU in the referendum

One year after the novel was published, the UK joined the Common Market. A referendum was held two years later in which the electorate voted to remain.

Dr Hugh Pemberton, a historian at the University of Bristol, says even the idea of the UK holding a referendum was "prescient" for 1972.

"Britain had never had a referendum at that point, though they had been held in other countries," he says.

Du Maurier also anticipated how sections of society would come to view the EU as a malign force.

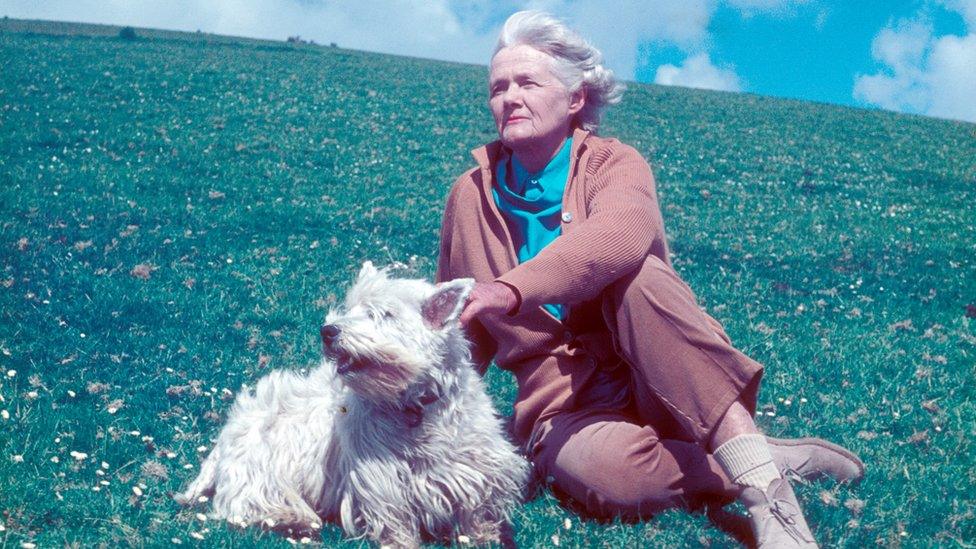

Like many of her novels, Rule Britannia is set in Cornwall - a region which voted Leave in June.

In the book, it's the Cornish people who initiate the resistance against the new union between the United States and the UK.

Du Maurier photographed near her home in Cornwall, a setting which inspired many of her novels

"The obvious analogy is the feeling they [the Cornish] were being run by the EU," Prof Taylor says.

Du Maurier's England also remains a divided political nation, with London-based characters such as the prime minister and financiers showing support for union with the United States, while much of the rest of the country fiercely resists.

In the 2016 referendum London was the only English region which voted to remain in the EU.

Novelists Bill Broun and James Hawes, whose works have more recently anticipated Brexit, agree that Du Maurier was on the mark.

"A big cause of Brexit is London-centrism," says Broun, whose debut novel Night of the Animals imagined a dystopian Brexit world.

"There's almost a cultural industry of sneering at the provinces," he says.

For Mr Hawes, author of the 2005 satire Speak for England, Britain's exit from the EU was precisely the result of those cultural divisions.

"It's all because the Westminster elite didn't see the concerns of ordinary people," he says.

Du Maurier also hints that nostalgia for past political arrangements - particularly when the UK was closer to the Commonwealth nations - were behind the referendum result in Rule Britannia.

After the vote, one character expresses delight at plans for the "English-speaking countries" to come together, claiming "you won't get the foreigners trying to push us around now".

Historian Matthew Francis said there were echoes of Rule Britannia in the 'take back control slogan' of the Leave campaign

Dr Matthew Francis, a political historian at the University of Birmingham, says variants of that "foreigners" argument were "definitely" part of the 2016 Brexit campaign.

"Obviously one of the key slogans was 'Vote Leave, take back control' and that was all about supposedly Britain leaving the EU and power being relocated from Brussels back to Westminster," he explains.

Closer economic ties with the Commonwealth were also presented as one "possible economic outcome" by Leave campaigners, he says.

In Du Maurier's novel, the UK faces rising prices and "acute" unemployment after leaving the Common Market.

Those events have not happened in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 referendum, but Mr Francis says we should not write them off yet.

"Obviously leaving has had some effect [on the British economy] - just look at the pound", Mr Francis says, referring to the fall in sterling since the EU referendum result.

But one major aspect of the novel is likely to remain fictitious, according to Mr Broun - the occupation of the UK by American forces.

"I think if that happens, it would be a dark day, that's for sure."