The Suez Emergency: The forgotten war of the conscript soldier

- Published

Thousands of national servicemen were sent straight from basic training to the Suez

Sixty-five years ago thousands of British conscripts were sent to Egypt to defend the Suez Canal in the wake of rising Egyptian nationalism. Poorly trained and under-equipped, they faced a brutal and bloody situation, protecting British interests in a conflict they wanted no part of.

In October 1951 a tense stand-off between the British and Egyptian governments broke down over the number of UK troops stationed in the country. In response, the British government mobilised 60,000 troops in 10 days, in what was described as the biggest airlift of troops since World War Two, external.

It was the beginning of the end of Western control of the Suez Canal and the start of the three-year Suez Emergency, which has been described as a "forgotten war fought by a forgotten army".

More than 60,000 troops were mobilised in just 10 days to shore up the British troops already based in the Suez Canal Zone

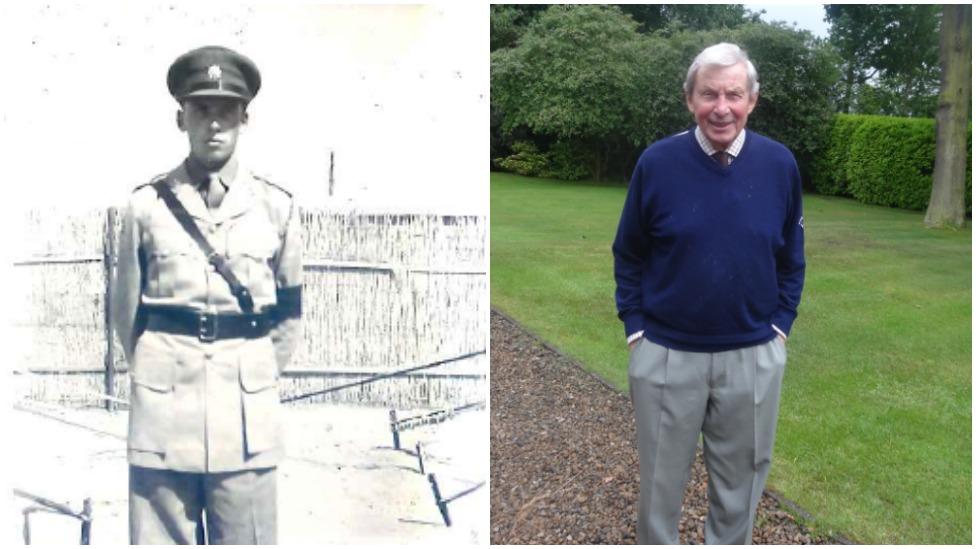

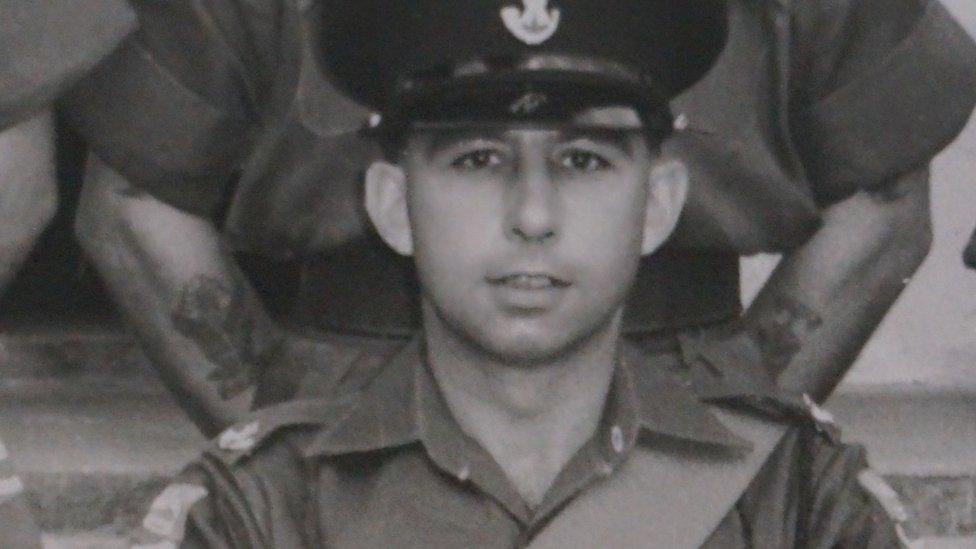

On the front line and defending the dying days of Britain's colonial interest in Egypt were men like Emmanuel Clark, who was 18 when he was called up for national service in 1951.

Just weeks after completing basic training, the dock worker from Fleetwood in Lancashire was sent to Egypt. "Everybody had to go in and if you were stuck in a mundane job you looked forward to it," he said.

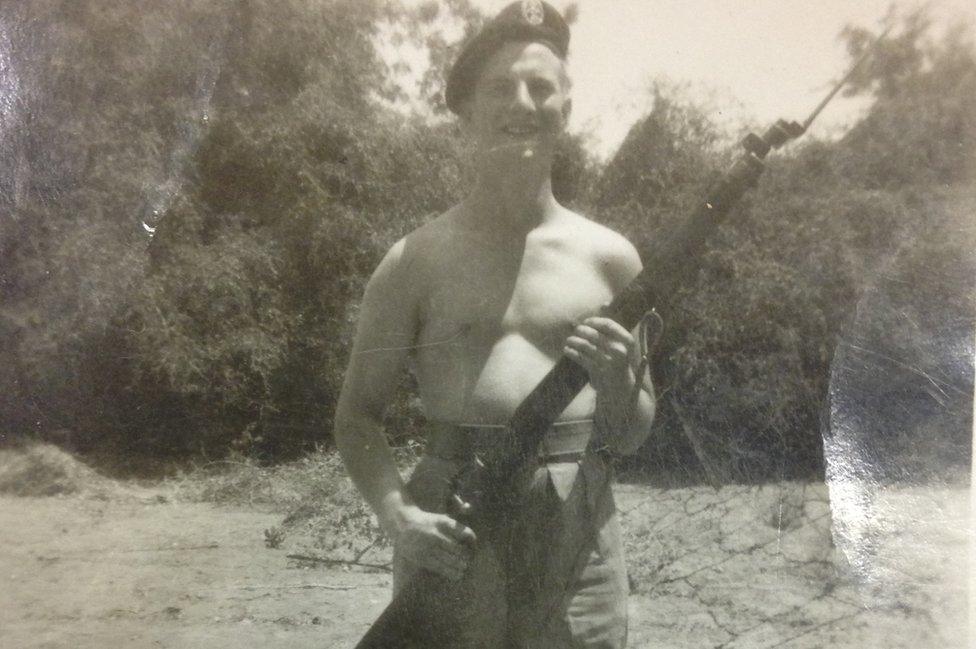

Emmanuel Clark was 18 years old when he was sent to Egypt

In the years after World War Two the British government was struggling to maintain its colonial empire in Egypt and beyond; national servicemen were seen as having a crucial role in keeping control.

By the 1950s males between 17 and 21 had to spend two years in the armed forces, with nearly two million going through national service between 1939 and 1960.

They were deployed all over the world to protect British economic and strategic interests - and nowhere was more important to these than the Suez Canal Zone.

"You didn't know who the enemy was," said national serviceman Emmanuel Clark, "it was a nasty business"

Opened in the 1880s the British-French-owned canal, which connected the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, provided Britain with a shorter shipping route to its empire but also to the crucially important oilfields of the Persian Gulf.

In 1936 a treaty was signed with Egypt that agreed the British could stay in the country but concentrated in the Suez Canal Zone, an area running along the length of the waterway.

"Britain needed Egypt and the Suez very, very badly... it wasn't going to give it up lightly," said author and historian Dr Colin Shindler.

But Egyptian nationalists, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser, fought back and demanded a revision of the treaty and the immediate withdrawal of all British troops.

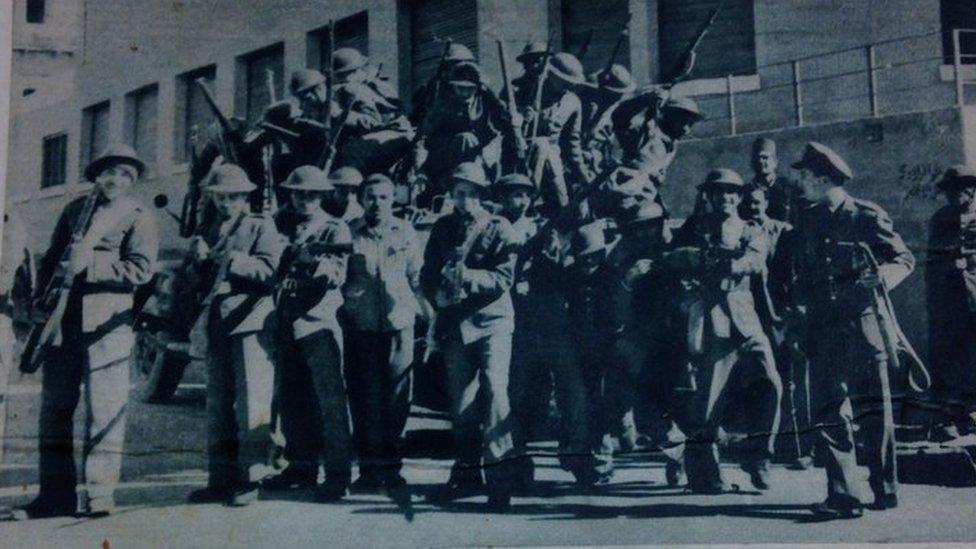

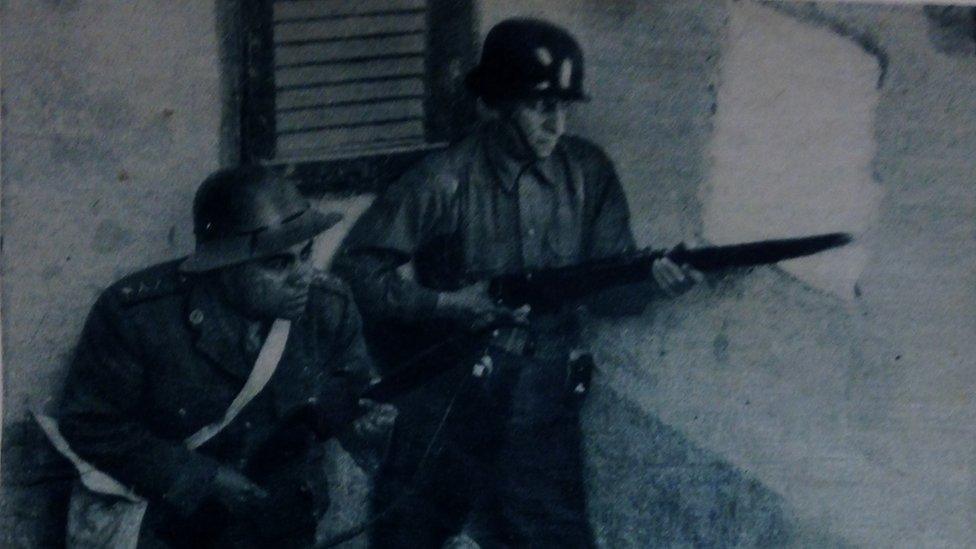

Cuttings from the Egyptian press show police officers joining forces to fight the British

On 16 October 1951 Egyptians stormed the Army's Naafi storehouses in Ismailia. A British soldier was stabbed and two Egyptians were killed in clashes. Egyptian volunteers rushed to join the Liberation Battalions, as the Muslim Brotherhood branch in Ismailia declared a jihad against the British.

"The Egyptians were better equipped and had better arms... in a lot of cases you would end up in the middle of a demonstration then somebody would open up with a gun - it was a nasty business," said Mr Clark.

"You didn't know who the enemy was," said Emmanuel Clark who was sent to the Suez Canal Zone in 1951

"If you went to Korea you knew where the front line was but in Egypt you didn't know who the enemy was, so you eventually you began to think everyone was the enemy and if they were in the line of fire, that was just too bad.

"We'd lost two or three guys to snipers so when we caught one, as soon as he divulged where the others were, I watched an officer shoot him. He was about 16 I think... but nobody bothered."

It was a shocking act to witness but Dr Shindler believes it was a product of the attitudes of the time: "There was a sense of 'we are white and superior and the ruling race'," he said.

"There was the attitude that that's how we treat the natives... don't for one minute think that they are your equals because they are not."

With hindsight Mr Clark is pragmatic: "We were being attacked and would have been overrun... you just accepted it and there was nothing you could do about it so you just got on with it."

The conflict placed huge pressure on inexperienced young men.

Michael Owen had just completed officer training when he was sent out to the Suez "at very short notice" in 1951

"I was 18 when I joined up and we were there to fight," said Michael Owen, 85, from Cheshire. He was sent out to the Suez in October 1951 just three months after completing his basic officer training.

"The situation was in turmoil and nobody knew what the Egyptian army was going to do, but it was vital for the British to keep that canal secure," he said.

Suez Canal Zone

In 1951, Egypt declared void the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that had granted Britain a lease on the Suez base for a further 20 years. Tensions led to the declaration of an emergency period until 1954.

In October 1956, the British and French-owned canal was nationalised by the Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, prompting military action by Israel, Britain and France to restore Western control - the Suez Crisis. However, they were forced to withdraw as the action did not have the backing of the USA.

During the period from 1951 to 1956 there were 450 British military fatalities in the zone.

Mr Owen, who joined the 1st Battalion Cheshire Regiment as a transport officer, said: "I was totally untrained and had to learn pretty quickly.

"It was an immense amount of responsibility."

'I loved the people, leadership and responsibility,' said Mr Owen, who was 18 when he went to the Suez

He found himself defending transport routes alongside the canal. "We were stationed in Port Said. Our job was to protect against terrorist attacks and we worked two days, one day off," he said.

"Learning on the job was very stressful - you had to learn how handle men considerably older and more experienced than you. Telling someone in their 30s what to do could be a very scary experience."

"The situation was in turmoil," said Mr Owen. This press cutting shows members of the Egyptian police force firing at British troops

As the conflict continued, more British troops were shipped in.

Eric Osborne, a furniture restorer from Ilminster in Somerset, was 18 when he was called up.

Such was the urgency of the situation that when he was sent home from training he was called back the next day and within 48 hours he was despatched to the Suez.

"I said I'd driven a tractor back home in Somerset and ended up driving the ration truck for 15 months," said Eric Osborne

"They didn't say what for - I had no idea," Mr Osborne said. "I'd never even heard of the Suez. We didn't find out where we were going until we were there.

"I was on death row for three months," said Mr Osborne, referring to his job driving a ration truck along a road by the Suez Canal.

Trucks travelling along the road were regularly ambushed and it soon acquired a reputation as "the most dangerous road in Egypt".

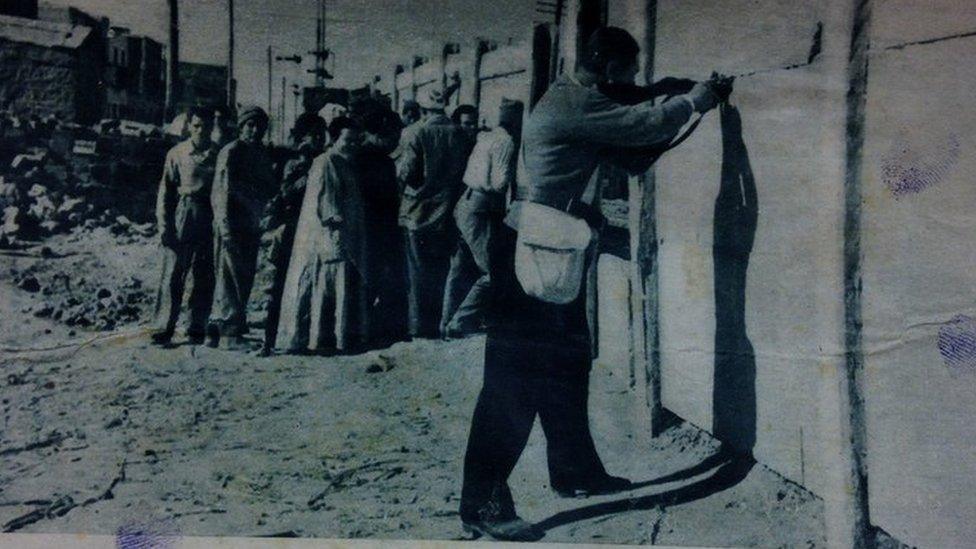

Cuttings from the Egyptian press show snipers in position opposite a filtration plant occupied by British troops

"I knew I had to do it... it wasn't an adventure, it was just something I had to do," he said.

"I have heard people saying 'fancy fighting over a body of water' but we had a perfect right to it and it made me grow up, that's all I can say."

"I was just doing my job, really, and positioning the guns," said David Rose, who was in the first wave of troops to land in the Suez

In an army made up of conscripts it was up to the regulars to help them adjust to military life.

Sgt David Rose, who led the first wave of the forces that arrived in the Suez, was tasked with showing the men who joined his platoon military life.

"In the platoon there were only five regulars, all the rest were national servicemen," he recalls.

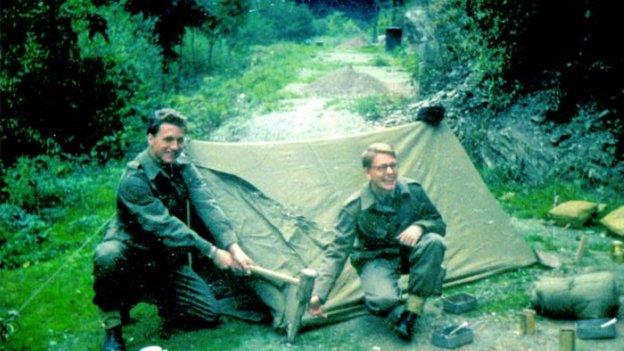

Sgt David Rose was tasked with helping to turn raw recruits into soldiers

"They slotted in and they were very good but they were funny people; a breed all on their own," said the 80-year-old former soldier.

"They all had to do it which they hated, but they loved it as well."

With a huge numbers of troops on the ground, the British were faced with a continuing crisis in Egypt.

As the emergency continued British troops were increasingly frustrated by their role in the Suez

Attitudes were hardening towards national service and the notion of "doing your bit for the country," said Dr Shindler.

"They [national servicemen] didn't want to spend a 'gap year' getting killed. They had no desire to be in the Army, no desire to stay in the Army, and just wanted to get back to the jobs they'd left behind."

However, about 70,000 thousand troops would remain stationed in the Canal Zone until 1954.

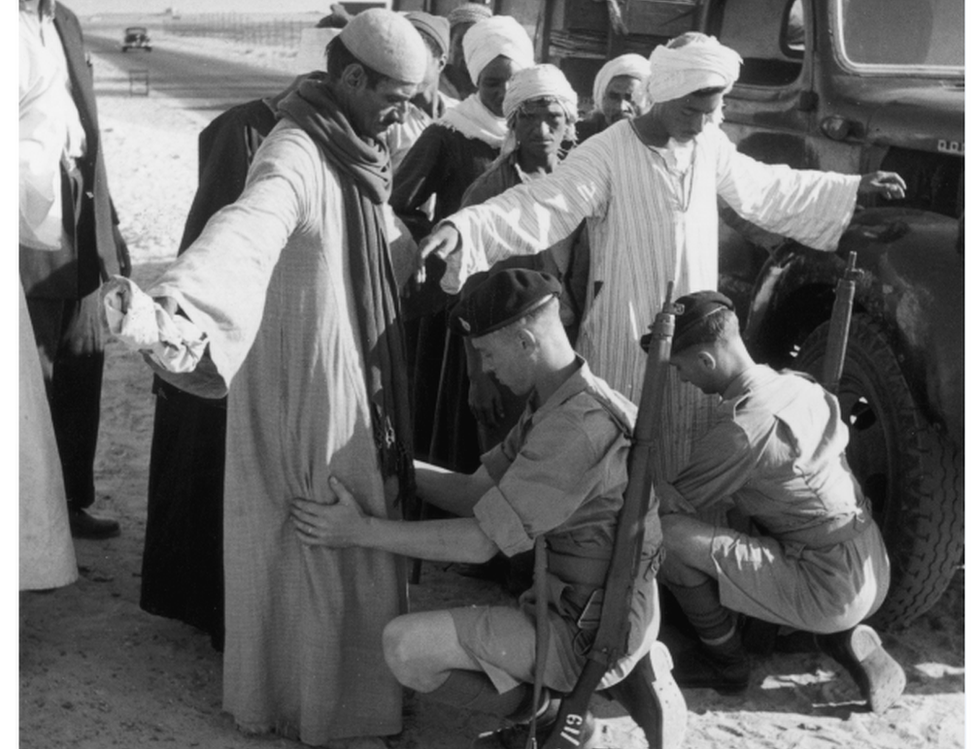

Living in huge tented camps the conditions were "very primitive", said Mr Clark: "There was no sanitation... more troops were going down with disease than action."

Thousands of troops lived in "primitive" conditions in the Egyptian desert

The living conditions of the troops were raised by Barbara Castle MP, external, who told Parliament: "Our men in the Canal Zone consider themselves to be the forgotten army of 1954 sitting as they are in a concentration camp behind barbed wire meditating on the futility of existence and wondering what is happening to their families."

"There was a huge difference in attitudes as the emergency came to an end," said Dr Shindler.

"The further we got from 1945 there was the belief that we were being ripped off and the bloody government was shoving us into a place we didn't know or care about.

"The idea of serving your country had dropped and there was a sense of the men just wanting to put on a sharp suit and go to the disco with some pretty girls."

"You might get guard duty running visiting troop entertainers all over Egypt," said Ken Foot, "the wolf whistles the women singers got - that was something else"

Ken Foot, 83, certainly didn't feel that they were all in it together. The printer's apprentice from London, who initially got a deferment from national service, went to Egypt when he was 21.

"Most of the battalion were national service blokes. They were a good bunch of fellas but you were all mixed up with the regulars who got more looked after than us.

"It wasn't noticeable but you'd find yourself bog cleaning a lot.

"Coming home felt bloody good - I felt like I'd done something but it was time to start living again."

- Published16 December 2015

- Published30 September 2014

- Published1 June 2015