Can Team GB help northern England rise again?

- Published

Melvyn Bragg's The Matter of the North begins on 29 August

Broadcaster Melvyn Bragg has called for the government to follow the model of Team GB's Olympic success and invest in the north of England. He believes the region, with its history of producing industrial and creative giants, has "a magic gene pool" which could put the UK "back on track".

Bragg, whose new Radio 4 series The Matter of the North explores the region's history, says its most important resource is "the people".

"We gave the British athletes the money and the training and the equipment and we beat a big country like China," he says. "If we gave the same resources to the North, just think what we could achieve.

"The North is different to the rest of the country. Different in the head and the heart."

It was also where the heart of the Industrial Revolution beat its strongest, which in Bragg's words, was "the greatest revolution in the world".

Mills clattered in Lancashire, Yorkshire ground out textiles and shipyards in the North-East sparked and clanged round the clock. The black gold of the coal mines brought prosperity to pit villages.

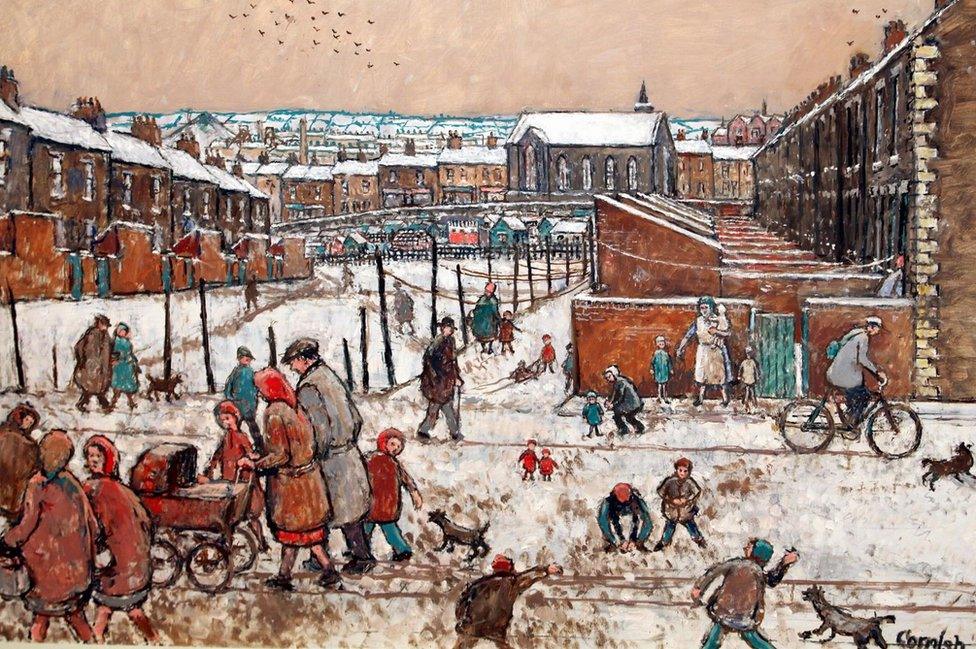

Norman Cornish was one of the "Pitmen Painters"

But by the 1960s and 70s, mills were closing across Lancashire at a rate of almost one a week.

Shipbuilding has largely moved to Asia and the last deep mine in the UK - Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire - closed in 2015.

Could taking a similar approach to the Olympics return the North to its former glory?

Over four years, £350m was invested in various sports, which netted the country 67 medals in Rio. But Team GB's success wasn't just all down to the money. There was a deliberate honing in on sports in which GB would do well, such as rowing and cycling. Sports where the UK wouldn't win had their funding taken away and the resources were ploughed into more fruitful areas.

Cheaper production costs overseas have largely ensured there's no way back for manufacturing in the UK. So if the north of England can no longer succeed in that, what are the strengths it can focus on?

The Lake District attracts thousands of tourists every year

Tourism would seem to be a good place to start. The region's greatest gift is perhaps its landscape - the long line of hills and dales that bisects the region and is known as the Backbone of England. Sometimes rolling, often wild, occasionally majestic, the countryside draws tourists from all over the world.

Indeed, enjoying the countryside is something that the North can lay claim to having invented, according to Bragg.

"People used to fear nature until the genius of certain people brokered a new relationship with the natural world," he says.

"The Romantic movement, people like [the Cumbrian born] Wordsworth, led to us realising nature is not the enemy. Now people go there and they just want to wander around."

It's an aspect Welcome to Yorkshire is keen to exploit. Chief Executive Gary Verity says he's keen to persuade new visitors "from around the UK and beyond" to make Yorkshire their destination of choice.

Cathy from Wuthering Heights roams the moor

The coast, as well as the moors, remains a big draw, with Scarborough attracting record numbers of visitors.

Major port cities such as Grimsby, Hull and Newcastle are interspersed with rocky cliffs, windswept beaches, quaint fishing villages and bustling, family-friendly resort towns.

It is a landscape that has seeped into the North's cultural output - a culture that Bragg believes is as strong and distinctive as any nation's.

Think Cathy and Heathcliff on the Yorkshire Moors, Wordsworths' wandering clouds and Mrs Tiggywinkle in the Lake District. The Calder Valley's sweeping moors, dramatic hills and winding canals were home to Poet Laureate Ted Hughes, inspiring some of his earliest poems, including The Thought Fox, external.

Phillip Larkin was a librarian in Hull, Whitby inspired Dracula, and it's easy to imagine John, Susan, Titty and Roger, from Swallows and Amazons, still pottering about on Derwentwater.

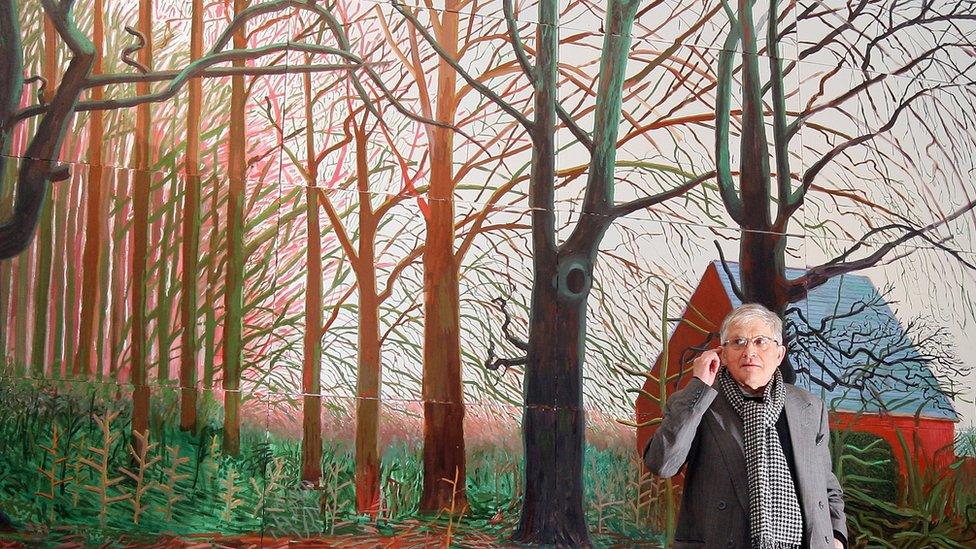

David Hockney, from Bradford, is regarded as one of the country's greatest artists

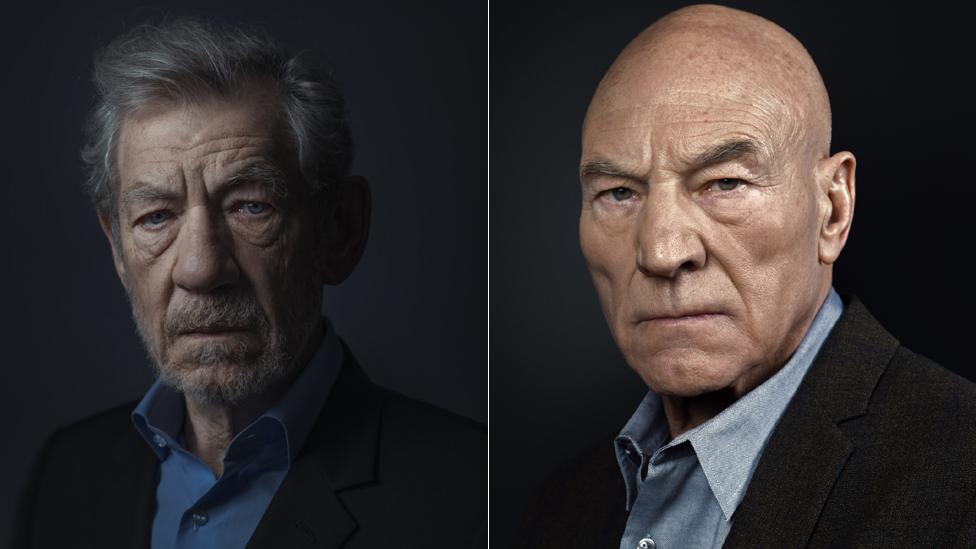

In the arts, the Pitmen Painters - a celebrated group of miners-turned-artists who rose to prominence in the 1930s - chronicled life in the coal-mining town of Ashington, Northumberland. Their near cousin LS Lowry has a permanent display of his work in a specially-built gallery in Salford Quays.

David Hockney, arguably the UK's most important living artist, is from Bradford and remains staunchly northern.

Musically, the North has given us more bands than you can mention; The Smiths, Joy Division and Echo and the Bunnymen to name but a few.

The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic has been performing concerts since 1840, making it one of the oldest orchestras in the world, while Manchester's Bridgewater Hall houses the 158-year-old Hallé.

And Hull has been named the UK's next City of Culture in 2017, beating Leicester, Dundee and Swansea Bay along the way.

It's an achievement people have high hopes for.

Brian Lavery, a writer and lecturer at the University of Hull, says: "This is going to filter down to the next [playwright] John Godber, who's now sitting in a primary school classroom somewhere, to some kid playing air guitar in front of his bedroom mirror, to somebody writing poetry in their attic."

However, while it's all very well having art and music, nowhere can prosper without the infrastructure - and that costs money.

The Northern Powerhouse - an attempt to corral the North's population of 15 million into a collective force to rival that of London and the South East - is the government's latest attempt to boost the region and reduce the economic gap between it and England's wealthy south.

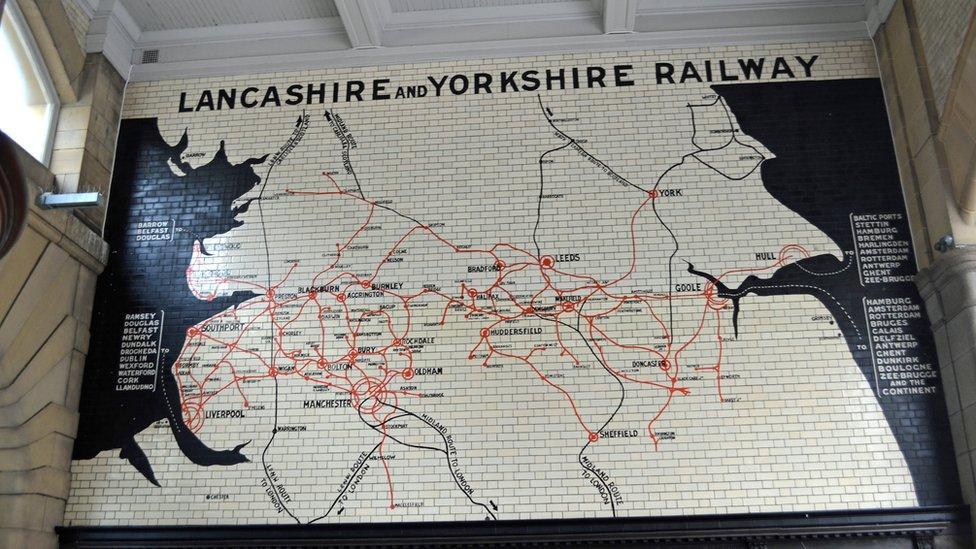

The distance is physical, as well as cultural, so one of the Northern Powerhouse's main aims is an improvement in transport links which will bring the region together and allow its towns and cities to compete as one major economy, rather than against one another.

Travelling the 60 miles between Carlisle near the west coast and Newcastle, near the east, takes 1 hour 37 minutes on a dilapidated train service.

Bragg believes the money earmarked for the HS2 line from London to Birmingham would be better spent on the North.

"I mean, going from Cumberland to Newcastle - it's a Roman road," he adds. "It makes you weep.

"This Northern Powerhouse - it's about time something was actually done. But so far the government's not shown any heart for it."

But the Northern Powerhouse is a concept, rather than any actual, physical thing at the moment," explains Ed Cox, of think tank IPPR North, who lives and works in Manchester.

"There is a task now for the government to be absolutely clear that the Northern Powerhouse does extend to all parts of the north and it isn't just a Manchester thing."

While the region's role as an industrial powerhouse may be in the past, the North is still at the forefront of technology.

The first human embryo to be cloned, external was at the International Centre for Life in Newcastle upon Tyne. About 600 people from 35 different countries work there, including researchers, doctors and nurses in the fields of genetic medicine and rare diseases.

Some of the UK's biggest tech businesses, such as Sage, the software group, and The Hut, the online retailer, are also in the region.

Tech North, external, a government agency set up to promote the sector, says there are nearly 300,000 digital jobs in the region, with companies accounting for almost £10bn in economic value.

The North's fourth major strength is sport - and it's not just the footballing giants of Manchester and Merseyside.

Famously, Yorkshire won so many medals in the 2012 Olympics it would have finished 12th in the medals table were it an actual country.

In Rio 2016, Nicola Adams from Leeds retained her Olympic boxing title, while the county's Brownlee brothers took gold and silver in the triathlon.

Jack Laugher from Harrogate took gold in the synchronised springboard diving - along with his City of Leeds Swimming Club-mate Chris Mears.

The first two stages of the 2014 Tour de France were also raced in Yorkshire and were backed so fervently that nearly five million people turned out to watch at the roadside.

We can also thank the north for the Grand National, rugby league, whippet racing, pigeon fancying, ferret legging and Geoffrey Boycott.

Local butchers Appletons created a "pie-cycle" out of pork products to celebrate the Tour de France passing through

The North has a lot to overcome before it can rise again; the decline in industry, decades of underinvestment, rickety infrastructure.

But Bragg is adamant it can and it will - and will do so without losing any of its quintessential character.

"It's a wonderful part of the world and like most people who've been born and brought up in the North I feel this is as much a country as any more neatly geographically defined place on the planet," he says.

"The future of the North depends on investment and training. The most important thing about the North is the people.

"They're sure of themselves, they know their own worth and it's not being realised."

The Matter of the North will broadcast on weekdays on BBC Radio 4 at 09:00 BST from 29 August - 9 September

- Published14 May 2015

- Published21 October 2014