Patrick Warren and David Spencer: The mystery of the Milk Carton Kids

- Published

On a cold December night 20 years ago, two boys went out to play. Two hours later, they vanished. They have never been found and nobody has been charged over their disappearance. So what happened to the friends who became known as the "Milk Carton Kids"?

It was the day after Christmas.

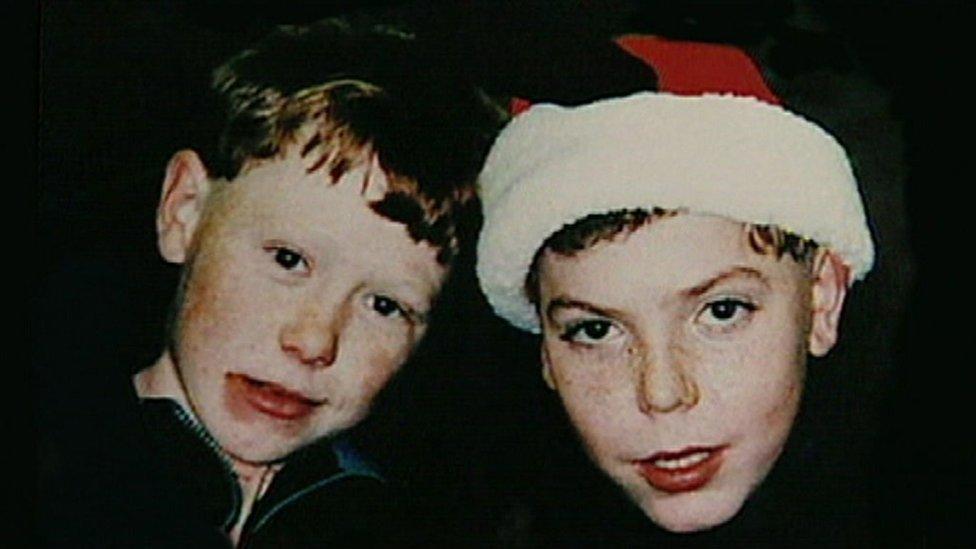

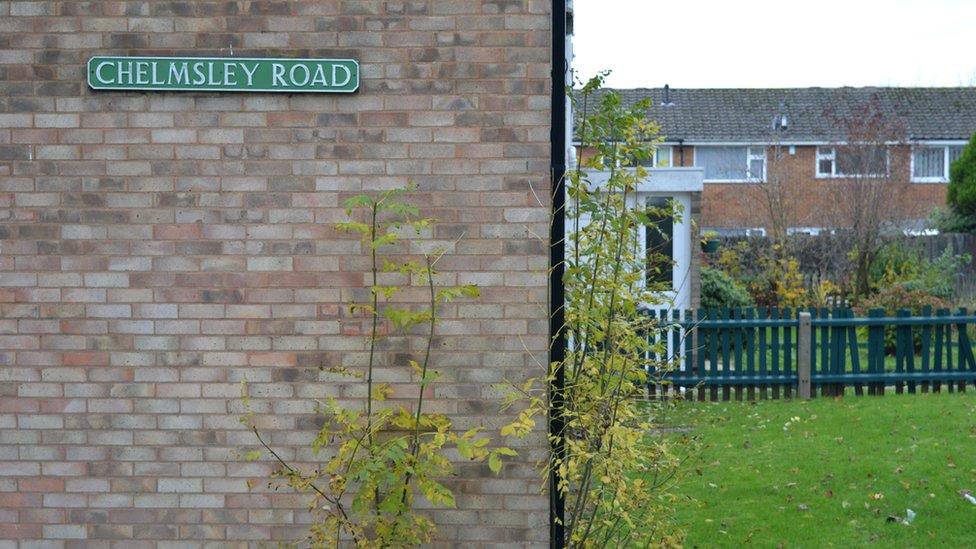

Patrick Warren and his friend David Spencer had spent the day together, playing near their homes in Chelmsley Wood - a sprawling, working class estate on the edge of Birmingham.

Despite their young age - 11 and 13 respectively - they roamed the estate until close to midnight, when David returned to his home in Circus Avenue.

He told his mother he was going to spend the night at Patrick's brother's home, a short walk away.

But instead of heading straight there, the boys decided to stay out a little longer.

The likely route the boys took before they disappeared

Together they drifted unnoticed in the cold and dark, past houses lit up with Christmas decorations.

Patrick was riding his new red bicycle - a present given to him the previous day - while David was on foot.

They made their way down a hill and crossed the road to a petrol station, just minutes from their homes, where they asked an attendant for a packet of biscuits. The attendant then saw them walk away towards Chelmsley Wood Shopping Centre.

The time was 00:45 GMT. It was the last time they were seen alive.

Warning: This report contains some swearing

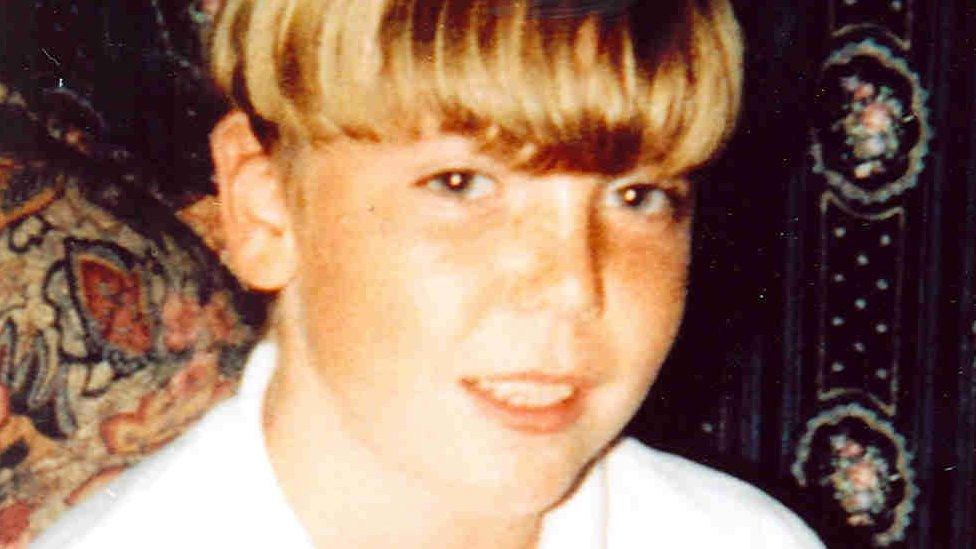

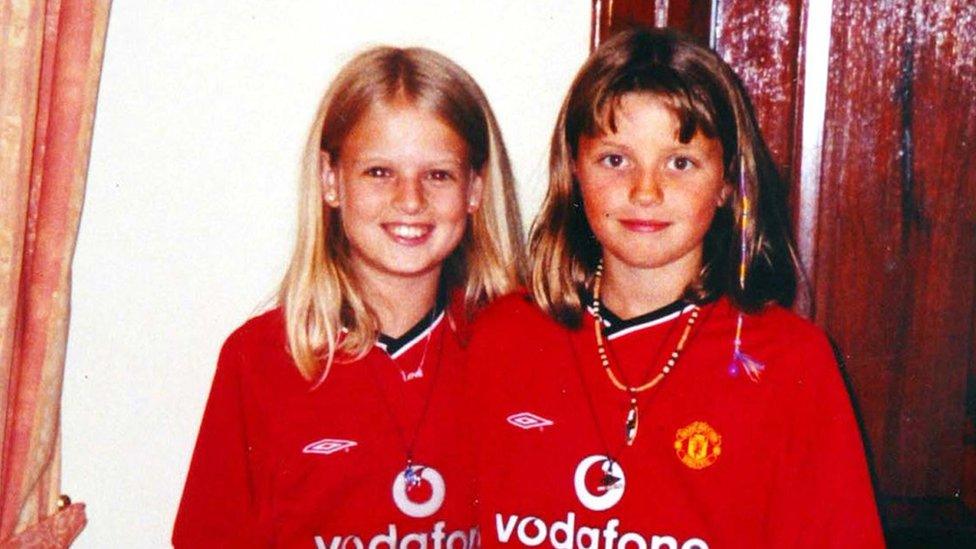

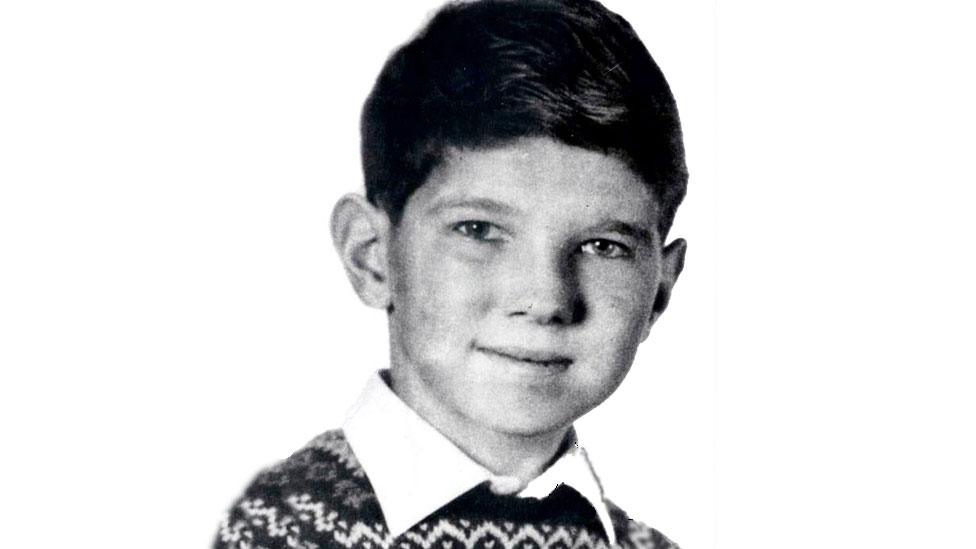

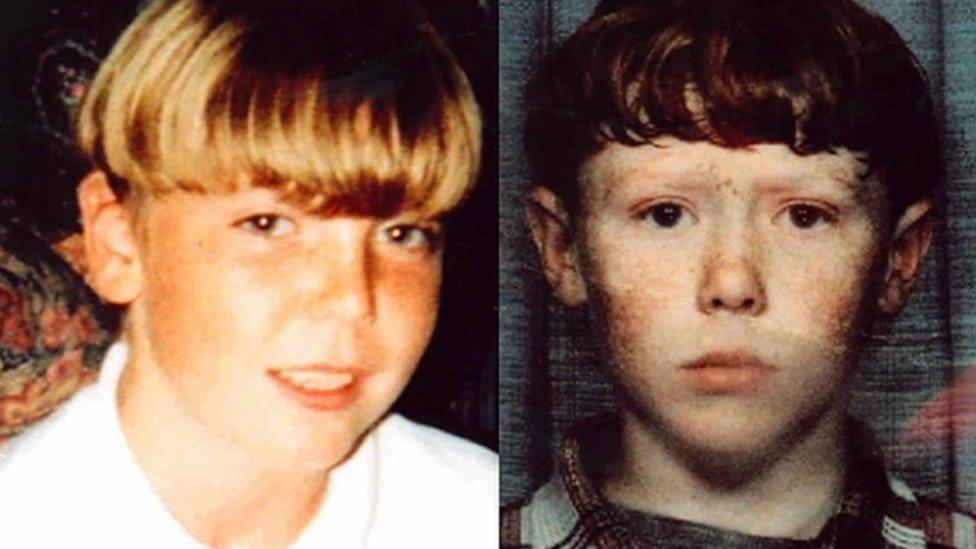

Patrick - known as Paddy - was one of seven siblings from an Irish family. He played football, liked noodles and used to rib his mum about her Irish accent when she lost her temper.

"He was a bit on the wild side," Bridget Warren said in 1997. "There's no point saying he was an angel, because he wasn't.

"I would say he was cheeky. But other kids' mothers used to say, 'Paddy is a terrific little lad', even his teachers said he was a good lad."

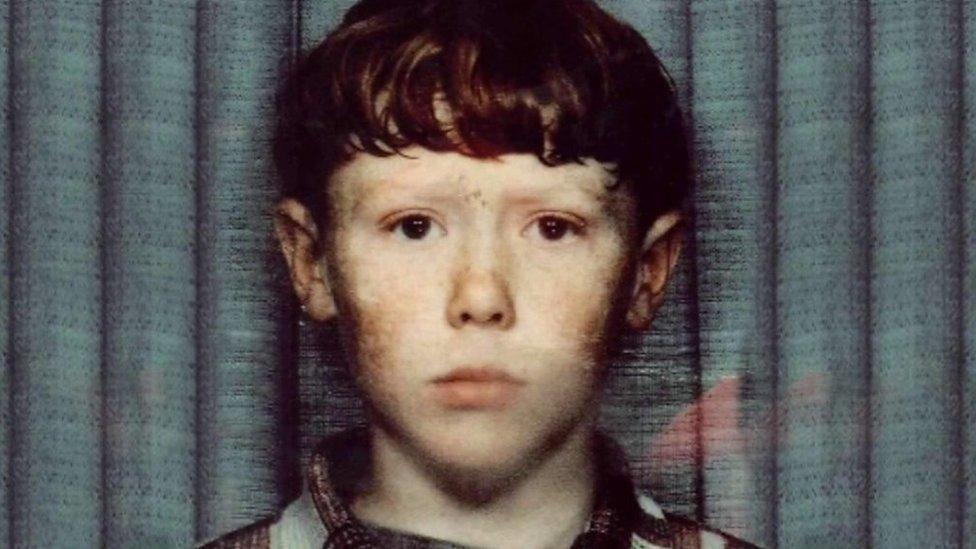

David, a keen boxer, was remembered by his mother Christine O'Toole as "adorable, a lovely lad" - but he also had a troubled side.

Petty misdemeanours had landed him in and out of youth court and he was eventually excluded from mainstream schooling, aged 12.

"He didn't like discipline, you couldn't tell him what to do," his mother said one year after his disappearance.

"He was aggressive; if someone caused him grief he took the law into his own hands and used force to keep them off his back, which was unacceptable."

A former teacher at Coleshill Heath School, from where David was excluded, recalls a bright boy who "had quite a presence".

"There were a significant number of boys who were troubled, but David was different," he said. "It was his unpredictability - you couldn't tell with him when something was going to go wrong.

"When he wasn't found, we were surprised. That was one of the things that always puzzled us - he was one of the most streetwise pupils we had at the time."

In the days that followed, police treated the boys' disappearance as a normal missing persons inquiry. They knocked on doors and spoke to neighbours; they searched buildings and checked the places they were known to play.

The force made appeals in the local papers urging them to come home. Officers spoke of being concerned for their welfare, but in the same breath stressed they were "streetwise".

It was a word that cropped up on numerous occasions in the weeks that followed.

Although there were no confirmed sightings, senior officers told the media there was no reason to believe the boys had come to any harm. They speculated they might be playing a "big game" or staying with friends. A £500 reward was offered for information on someone who might be sheltering them.

In late January, police held a press conference where the boys' mothers appealed for them to come home.

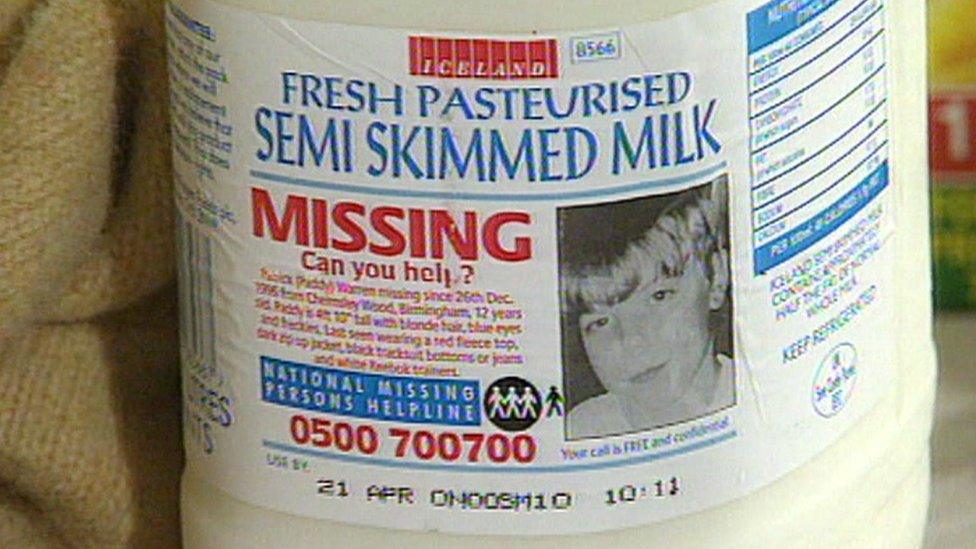

Then in April, Paddy and David became the first children to appear on four-pint milk cartons in 770 Iceland stores, as part of a campaign by the National Missing Persons Helpline.

The charity hoped the scheme would be as successful as its American counterpart, which had made famous the faces of missing children, such as its first poster boy, Etan Patz.

The local media nicknamed the boys "the Milk Carton Kids", but after a four-week run on the side of the cartons there were no major leads. The appeal also failed to catapult the case to the attention of the national media.

At a press conference in March 1997, David Spencer's mother, Christine, said she was worried for her son

Local reporters were clear police regarded the boys as runaways. But, with the benefit of hindsight, clues to the contrary were there.

Paddy's new bike - a prized Apollo Laser - had been found, apparently abandoned, behind the petrol station where they were last seen.

Though it was discovered on 27 December, officers did not realise it was Paddy's until several weeks later.

Should this development have been treated more seriously?

Mark Cowan, a former Birmingham Mail crime reporter who covered the case for 15 years, believes it should have indicated the boys were not runaways.

"If you're going to run away, why would you dump your bike at a petrol station?" he says, putting down his drink and speaking up over the noise of the busy coffee shop.

"It was his Christmas present, it was a big present for him, it was probably his most treasured possession.

"To leave it within 24 hours of getting it... if you're going to run away, you take your bike, if nothing else, to cover a lot more ground."

Paddy's red bike was found behind the petrol station where the boys were last seen

Mr Cowan has just returned from a diving expedition on the other side of the world, but the jetlag does nothing to blur his memories of the case.

He first met the boys' families in 1997 and still wonders how seriously the case was taken by police. He suspects officers decided early on it was a matter of "two streetwise boys running away from home" and says officers did not change that mindset early enough.

"I've always wondered whether it was treated as [a missing persons case] for as long as it was because they were two boys from a council estate in a poor part of town, who no-one but their families and friends had any sympathy for."

He pauses.

"I would like to think that isn't true and I would like to hope that's just my opinion. But it was always one of the things that was in the back of my mind."

One person who believes the boys' background influenced how police treated the case is Prof David Wilson, a criminologist at Birmingham City University.

He and his colleague, Prof Elizabeth Yardley, who have studied the case in depth, believe officers failed to treat Paddy and David as the vulnerable children they were.

"They were made out to be much more adult," he says. "There was a great deal of attention on describing them as not being good at school, one of them chain-smoking.

"There was a sense that they weren't really children, when in fact they were."

Prof Wilson adds: "Culturally, how you approach the first 48 hours in this type of case is either with urgency or 'they'll turn up because they're runaways'.

"If it had been two boys from [middle class] Solihull that went missing, that case would've been treated initially very differently.

"And it's about that word we're never allowed to use, class - this was about a class judgement that was made which was prepared to see them as runaways, as opposed to vulnerable."

Criminologist Prof David Wilson believes the boys' working class background affected how their case was treated

Ten years after Paddy and David disappeared, the case was reviewed by West Midlands Police.

One of the lead officers on the review, Det Ch Insp Mick Treble, is now retired. At his home in Staffordshire, he is redecorating, his face splattered with paint - but he agrees to talk about the boys.

"They were remarkably young when they went missing and when I looked at the case I couldn't believe children of that age could disappear and there not be a major outcry," he says.

"I was serving in the force at the time [they disappeared], but it never came across my radar.

"At the time there were a lot of big things going on in the force and the case seemed to get overshadowed."

Just a few days after the boys disappeared, 17-year-old Nicola Dixon was raped and murdered in leafy Sutton Coldfield, seven miles away from Chelmsley Wood.

Nicola Dixon was found in a graveyard on New Year's Eve 1996

The killing of a middle class girl in a graveyard on New Year's Eve dominated not just regional and national news, but police resources.

"There was always a feeling that the Nicola Dixon case, understandably, sucked up resources," he says.

"The difference is remarkable if you compare the two cases - the resources and effort put into her murder case and that of two young boys going missing.

"When you looked back, there did seem to be a divide.

"But I don't think that in any way took anything from the investigation."

Missing children and the media

Mr Treble is adamant police made the routine inquiries required of a missing persons investigation.

"When someone goes missing you speak to the last people that saw them and the families," he said.

"You search buildings, haunts they frequented, places they played, friends to see if anything went on at school... all the basic things.

"Looking at the case, that had clearly been done. The bit that didn't seem to get done was that when they're that age, a red flag should go up to look at whether something more sinister happened."

Though officers had investigated a number of false leads in the intervening years, by 2006 detectives were looking at the case as a "no body murder".

A full forensic investigation was conducted of the boys' houses, which revealed nothing untoward.

Photos of the boys were digitally aged to help with the appeal

Checks were made of the sex offenders register - which did not exist when the pair went missing - and known paedophiles living in the vicinity at around that time were questioned and ruled out.

A nearby lake was searched, as it had been in February 1997. Fields on the edge of Chelmsley Wood were explored, as were nearby mineshafts.

"I have no doubt that something sinister happened," says Mr Treble.

"There's a possibility they met with a very tragic accident in a place someone wouldn't have thought to look.

"The other possibility is they were taken away and murdered."

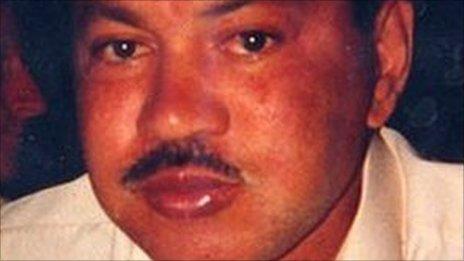

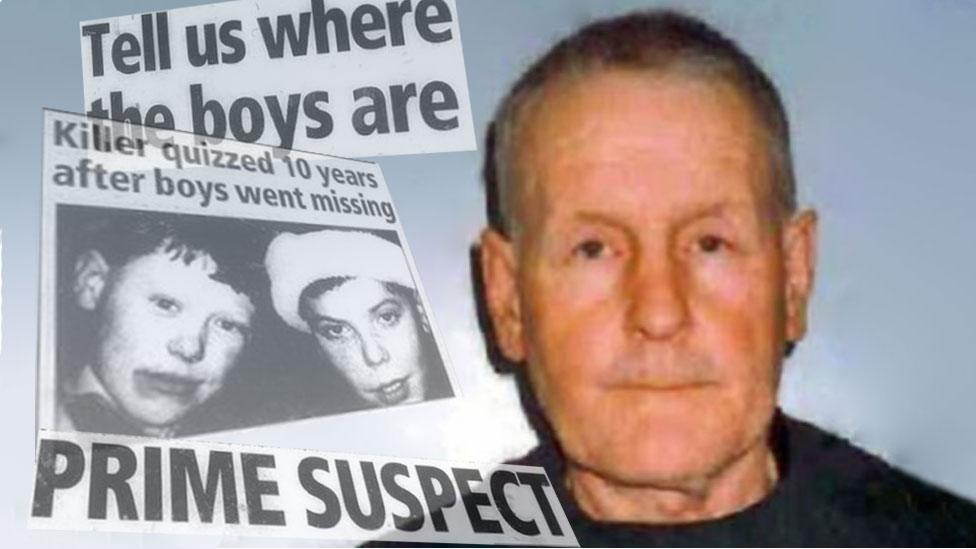

This is where attention turned to paedophile Brian Field.

At the time Paddy and David went missing, Field was living only a few miles away in Solihull.

Three years later he would be arrested for drink-driving in Chelmsley Wood. A DNA sample taken from him led to his conviction for the 1968 rape and murder of Surrey schoolboy Roy Tutill.

The former farm labourer had already served a prison sentence for kidnapping two boys in the 1980s. He remains the only person in British criminal history to have been convicted of such a crime, according to Prof Wilson.

Could he have killed Paddy and David?

"It's astonishing," says Prof Wilson. "You've got a specific modus operandi [of kidnapping two boys] and that modus operandi fits him.

"We know he was in the area, we know he worked and lived close by and therefore, likely used the petrol station where the boys were last seen alive.

"He was a landscape gardener and was therefore probably able to dispose of the bodies."

When the case was reviewed in 2006, Field was named as a suspect. He was questioned by detectives and officers also dug up land he used as a dumping ground at Old Damson Lane in Solihull.

But without evidence, they were unable to secure a confession.

Land used by Brian Field was dug up as part of Operation Stenley, a 2006 reopening of the case

The search at Old Damson Lane in Solihull was fruitless

"He had a van, he was in the area at the time, but there was nothing tangible to tie him to the boys," says Mr Treble, shaking his head.

"He had nothing to lose. We said, 'give the parents some closure and tell us what happened'.

"But it was a vehement denial. He said there was nothing he could help with."

Prof Wilson warns Field is unlikely ever to admit any involvement. He believes the only hope of securing a conviction is by finding evidence directly linking Field to the case.

"Most people think most murderers are going to go, 'it's a fair cop, guv' and give you the dramatic denouement they associate with crime drama," he explains.

"But most murderers never talk about it and are in fact very hostile when you ask about it."

The BBC wrote to Field in prison asking him to speak about the boys' disappearance, but he did not respond.

West Midlands Police says he remains a person of interest "due to his offending history".

Field is serving a life sentence for the 1968 murder of Roy Tutill

Paddy and David's disappearance is truly exceptional.

According to the Centre for the Study of Missing Persons, most cases of missing children are resolved within 48 hours and only 1% of cases are open for more than one year.

The National Crime Agency said most children who are murdered are killed within six hours of being taken.

Prof Wilson believes more could have been done in the early stages of the investigation after Paddy and David went missing.

"I hate mysteries because I think if you apply some logic and investigate it and ask the right questions and give it the right attention, they are solvable," he says.

"Had police investigated properly, they would have gone to Field's accommodation, they would have gone to his place of work, they would have spoken to the person in the petrol station and asked them if they had seen [Field] speaking to those boys."

Mr Treble agrees more could have been done in the immediate aftermath of Paddy and David's disappearance.

But he warns against judging police methods at the time by modern standards.

He points out how something as basic today as computerised records was not routinely available in the mid 1990s and the most advanced communications technology officers had was a pager.

"I think we could have thrown more resources at it in the early stages and ramped it up to something more serious," he says.

"But we shouldn't try to judge the tactics used in 1996 by today's standards, because they were the methods available at the time."

Det Ch Insp Caroline Marsh is the detective currently in charge of the case. She said the delay in escalating the case was in part down to the fact both boys had told their families the same story - that they were each going to the other's houses for the night.

"When they didn't come home and when they weren't immediately located, that was the story that was recounted - they were having some fun," she said.

"The view was that they were just being boys. It took several days and weeks before the realisation settled that something was really wrong and they weren't coming back.

"If that happened this Boxing Day, I can guarantee that the response would have been very different. The way we deal with missing persons cases today is very different."

She also takes issue with the suggestion that the boys were treated differently because of their background.

"I don't believe so," she said. "After the realisation [they weren't coming back] settled, there was a lot of concern for the boys.

"Over the course of that first year, the inquiry was taken very seriously."

Brother of missing boy says family want 'closure'

Det Ch Insp Marsh said the boys' case was an example of how times had changed.

"The term 'streetwise' was a term that was used in the past to describe children that could look after themselves. Today that's something that's seen as a vulnerability.

"A couple of young boys disappearing together is highly unlikely, it suggests there's been a serious incident or criminal act, which is why today [the case] sits with the homicide team.

"I think what happened is a reflection of how we dealt with missing persons cases 20 years ago. We have moved on a lot."

When a person goes missing, a full assessment is now carried out to determine the level of risk.

A child missing from home is usually treated as high risk and there is normally CID involvement within the first 24 hours.

In Paddy and David's case, however, CID detectives were not brought in until they had been missing for three months.

Today, it's hard to imagine how two boys could simply disappear. In a world where appeals can be seen instantly by millions at the click of a share button, it seems unthinkable Paddy and David's case remains unsolved.

West Midlands Police says its homicide team continues to investigate the case and actively follows up any new lines of inquiry, though there has been nothing significant to date.

At a press conference on Wednesday 21 December, Det Ch Insp Marsh urged anyone with information to come forward.

David's younger brother, Lee O'Toole, also spoke to the media. He said he found the hardest thing to deal with was not knowing where the boys' remains are.

"I am convinced there's someone out there that knows what happened to my brother," he said. "I am begging them to come forward.

"We need to find out where they are to put them to rest. That information could [allow] my family to move on. At the minute, we've got nothing."

On the estate where they lived, the disappearance of Paddy and David is still remembered vividly.

"It's still quite raw for people, even though it was so long ago," says Prof Yardley, who has interviewed residents about the case.

"You could see people welling up as we were talking to them. There was a sense that they felt the boys had been stigmatised."

But the boys are also remembered affectionately.

One man, when asked about them, leans in conspiratorially with a knowing smile. "You know they were little rogues, right?" he says good-naturedly.

Around the corner on Stella Croft, former dinner lady Val Short is walking her dog, Zachary.

She remembers David as a polite boy - "naughty, but kids are naughty", she says, her pet shivering in the brisk November wind.

Neighbour Kim Prescott remembers him fondly as "a bit of a troublemaker".

"He was a typical lad, he went off on his bike rides, he was quite adventurous.

"When I first heard he went missing, I thought he was just dossing around in someone's house.

"Being the type of kid he was, I thought, 'he'll be back'."

At David's childhood home in Circus Avenue, his mother Christine leans out of a window. She seems distant, as if she's given up looking for answers.

"What's the point," she says, of talking to the press. "Nothing good ever came of it."

Just a few minutes away, at Paddy's home on Chelmsley Road, the reception is similar.

His older brother, Derek, answers the door and shouts over his shoulder: "They're here about the boys."

Bridget shouts from the front room. "No! Don't talk to them!"

Derek turns to another man, chopping food in the kitchen. "They want to talk about Paddy."

"Not interested," he responds, without looking up.

Derek hovers in the doorway, seemingly unsure what to do. He agrees the boys didn't get the press coverage they deserved, says police didn't do enough to find them.

"It was a fucking joke," he adds, before finally shutting the door.

Credits

Author: Lauren Potts

Additional reporting: Danielle Dwyer

Photography: Stephanie Barnard & Bethan Bell

Editor: Dave Green

- Published21 December 2016

- Published31 May 2013

- Published24 August 2012

- Published3 April 2012