Hill figures: The stories behind the scars on England's skin

- Published

Hill figures, emblazoned like scar tissue across England's undulating landscape, hark back to times when gods were honoured and appeased by grand gestures.

Although horses - and some well-endowed giants - are perhaps the most well-known hill figures there are also some more unusual creatures and carvings.

A lion stands proudly in Bedfordshire. A kiwi in Wiltshire is a testament to the homesick New Zealand soldiers once stationed nearby.

Here are the stories behind some of the enormous symbols which have become part of the country's very fabric.

The mane attractions

Is it a horse or a dragon? It is said that when King Arthur awakes the hill figure will rise up and dance

The Uffington Horse, in the Berkshire Downs, is considered the oldest hill figure of them all. Carved in the Iron Age, there has been an unbroken chain of people caring for this prehistoric monument for the past 3,000 years.

Soil tests show the horse has been there since between 1200 BC and 800 BC. There are plenty of legends associated with both the figure and with nearby Dragon Hill. There have even been suggestions the horse is in fact a dragon.

One tale is that King Arthur will one day wake when England is in peril. When Arthur rouses (although legend has it he fought against the English, so it would seem unlikely), the Uffington horse will rise up and dance on Dragon Hill, external. A similar creature is featured on old Celtic coins from 150 BC.

In fact depictions of horses are fairly common, with at least 24 across Britain - although some can no longer be seen.

Historian Dr Mark Hows, who studies hill figures, believes the figure represents the Celtic goddess Epona, protector of horses, and all the other horses are copies of - or at least inspired by - the Uffington original.

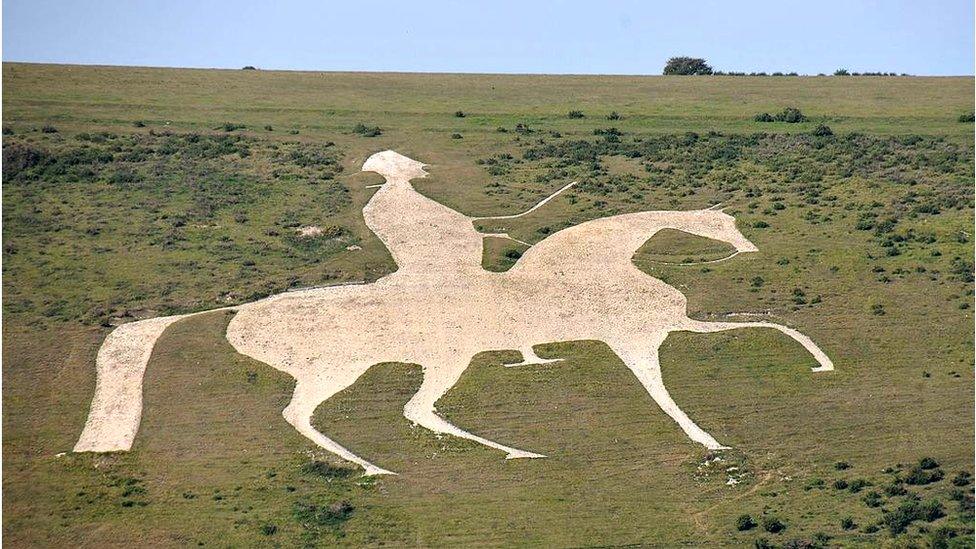

However, only the Osmington White Horse - a 260ft (79m) figure which prances across the South Dorset Downs - has a rider.

It was carved in 1808 in honour of King George III, who was a regular visitor to nearby Weymouth. The figure underwent something of a trial in 1989 when the BBC programme Challenge Anneka decided to restore it - but ended up damaging it, external.

It was properly redone in time for the 2012 Olympics, when it could be seen by television viewers of sailing events held in Weymouth harbour.

The Osmington White Horse was carved in honour of King George III

The rather rude giant

Although undoubtedly "anatomically impressive", the giant's origins are uncertain

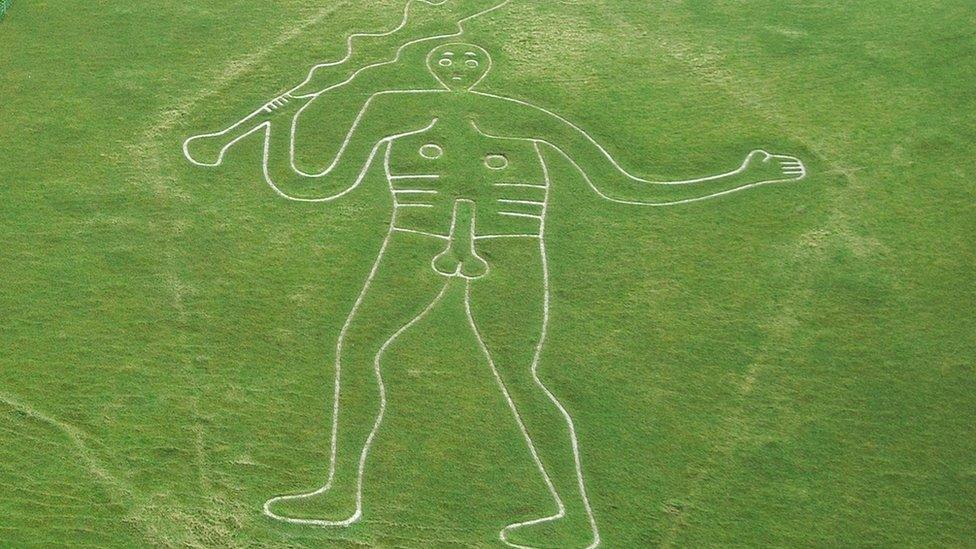

One of the most famous hill figures is the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset, which Historic England describes as "bold and anatomically impressive".

The 180ft-tall (55m) turf-cut figure of a naked man waving a club has prompted considerable debate over its origins.

Early antiquarians linked him with the Anglo-Saxon deity Helis, while others believe he is the classical hero Hercules. Still others posit he was carved during the English Civil War as a parody of Oliver Cromwell, although he is commonly believed to have some association with a pagan fertility cult.

A further layer of mystery was added in the 1980s when a survey revealed anomalies which suggested he originally wore a cloak and was stood over a disembodied head. There has also been a suggestion his significant anatomy is in fact the result of merging a smaller penis with a representation of his navel during a re-cut by the Victorians.

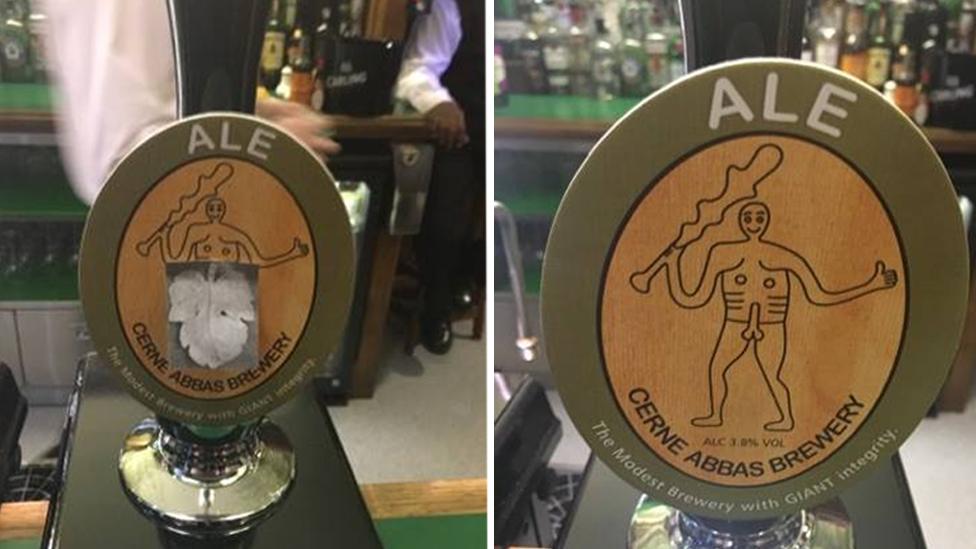

The giant has caused a few hot flushes in the past. Prudish politicians led to a version on a brewer's logo having his modesty preserved in a Houses of Parliament bar by the addition of a paper fig leaf.

And keeping with a political theme, pranksters recently attached giant letters spelling out "Theresa".

A photocopied fig leaf was added to the beer pump clip in a Houses of Parliament bar

Another giant

Cerne Abbas is not the only place to boast a giant on its hillside. Wilmington in East Sussex has its own "Long Man" - but he is a more modest sort than his Dorset cousin.

For many years up until the 19th Century, the Long Man was only visible when the sun was in a certain position, but since 1874 its shape has been marked out in yellow bricks.

The Sussex Archaeological Society describes him as "the mysterious guardian of the South Downs" and says there are many theories about his origin.

Some are convinced he is prehistoric, others believe he is the work of an artistic monk from the nearby priory, which would date him from between the 11th and 15th Centuries.

Roman coins bearing a similar figure suggest he belonged to the 4th Century and there may be plausible parallels with a helmeted figure found on Anglo-Saxon ornaments.

We may never know.

Kiwi in camp

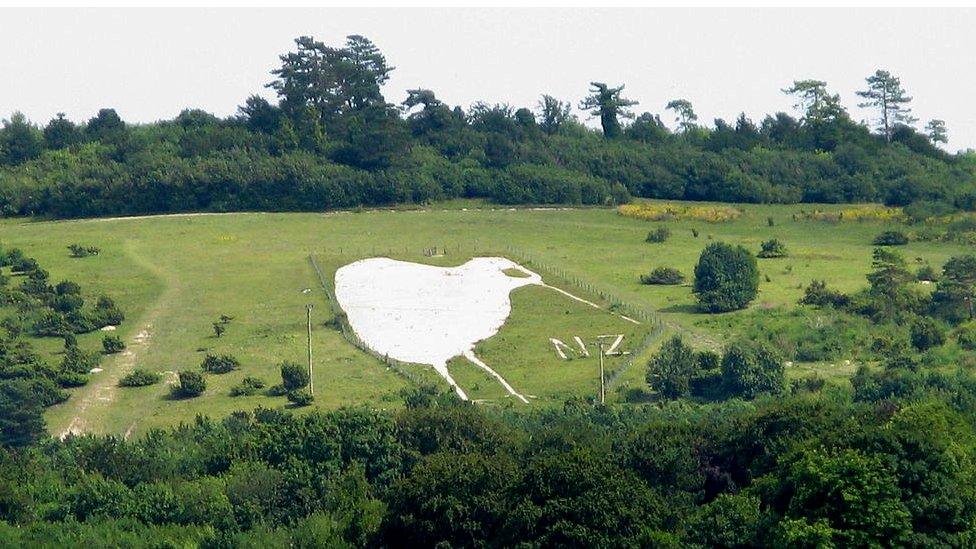

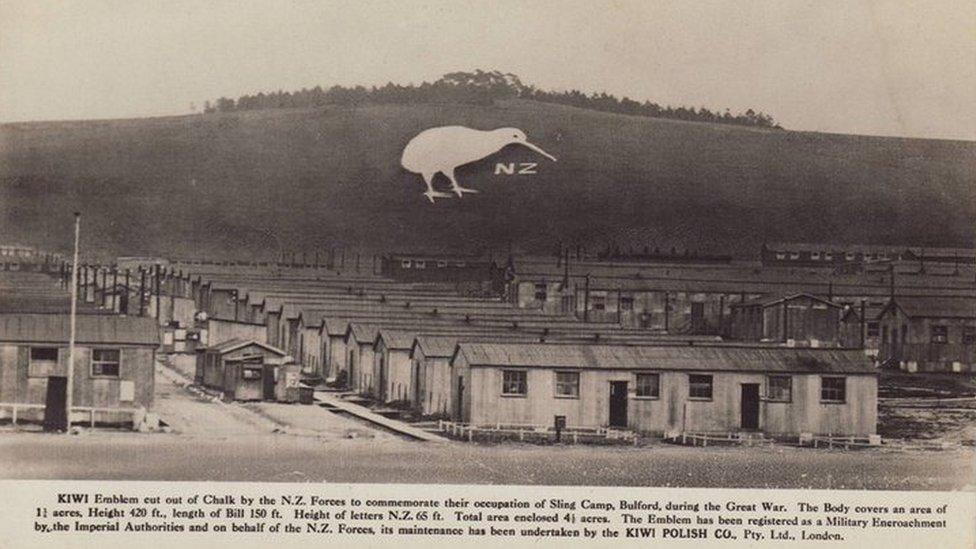

The Bulford kiwi photographed in 2013, following restoration and maintenance by a local scout group

In 1919, following the end of World War One, officers commanding restless and homesick New Zealand troops wanted a task to distract their men and keep them out of trouble.

Perhaps inspired by Wiltshire's large number of chalk hill figures - it has 13 horse figures alone - they despatched the soldiers to carve a kiwi in the hillside above Bulford Military Camp.

It was designed by Sgt Maj Percy Cecil Blenkarne from a sketch of a stuffed kiwi specimen in the British Museum.

The figure, the body of which measures 1.5 acres (6,100 m sq), was completed shortly before the troops went home.

It was then looked after by the Kiwi shoe polish company as an advert, until it was covered during World War Two in case it was used as a landmark by enemy aircraft.

Although the carving was neglected and nearly disappeared in the 1970s, it was restored close to its former glory in 1986 by a local scout group - which changed its name to the 1st Bulford (Kiwi) Scouts. It has now been given protected status.

A postcard from about 1919 shows the kiwi shortly after completion

Other remnants of military life can be found on Fovant Down, between Salisbury and Shaftesbury, where military insignia are carved.

Five of the Fovant Badges were created by soldiers during World War One, including the rising sun of the Australian and Commonwealth Military Forces, the Post Office Rifles and the Devonshire Regiment. The ACMF also had men stationed at the nearby Hurdcott army camp, where they cut a map of Australia.

The badges belonging to the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry and the Wiltshire Regiment were built in the early 1950s by the Fovant Home Guard, while the Royal Corps of Signals cut their badge in 1970 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the corps.

The YMCA emblem, which is not a regimental badge, was allowed to fade away in 2005 and can no longer be seen

A roaring success

But to find the largest of England's hill figures, one has to travel to Bedfordshire.

The giant 147m (483 ft) long lion was carved in 1933 to indicate the location of Whipsnade wildlife park.

Thousands of man hours over 18 months were spent digging the creature out of the hillside with pick-axes.

However, the outbreak of World War Two resulted in it being covered up again, amid fears it could help guide German bombers to the nearby towns of Luton and Dunstable.

Troops were brought in to help camouflage the landmark with brushwood, nets and manure.

After the war the lion was uncovered and spruced up again in 2005.

He is now visible for several miles across the Dunstable Downs.

- Published1 November 2013

- Published1 July 2012