When a lion prowled the streets of Birmingham

- Published

Frank Bostock and his lions catching up with the news

When considering which creatures have roamed the sewers beneath Birmingham, lions are unlikely to make the list. But on one fateful day in autumn 1889, a lion who had previously killed a man and mauled another escaped from a menagerie and did just that.

Travelling menageries were extremely popular in the 19th Century. Although zoos were starting to emerge in Britain, these were often socially exclusive or inaccessible, according to Dr Helen Cowie, a historian at the University of York.

Popular though they were, the typical menagerie's approach to health and safety was cavalier at best. Dr Cowie says they "were not too preoccupied" with security and there were "an alarming number" of escapes and accidents.

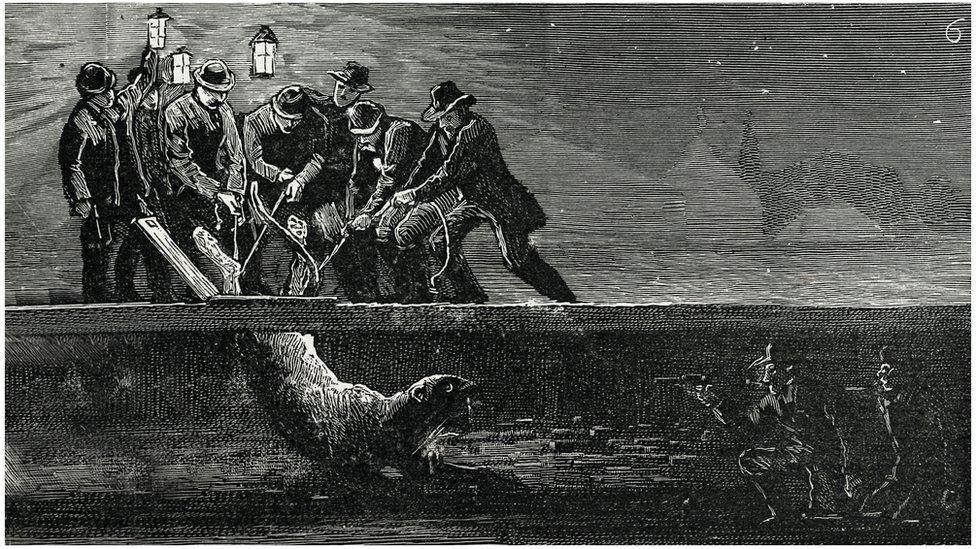

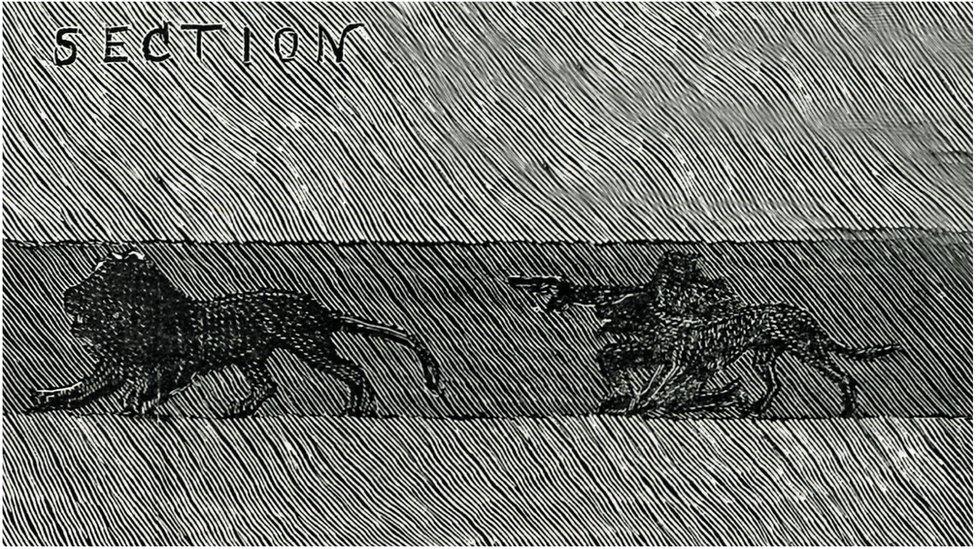

An illustration from The Graphic newspaper shows men pulling a lion from a sewer using a rope while two other men threaten it with guns

Frank C Bostock, the owner of a menagerie, was himself responsible for fooling both the public and the police over the whole lion-in-a-sewer affair. He later described the event as "thrilling".

World-famous as a lion tamer, having discovered the beasts were intimidated by chairs, he came from a long line of animal-displayers and was part of the Bostock and Wombwell, external menagerie dynasty.

Fiercely ambitious, according to researchers at the National Fairground and Circus Archive, Bostock established himself in the US and by 1903 an average of 16,000 people a day were visiting his menagerie on New York fairground haven Coney Island.

On returning to the UK Bostock brought back his idea of the "Jungle", a massive touring exhibition that moved from city to city.

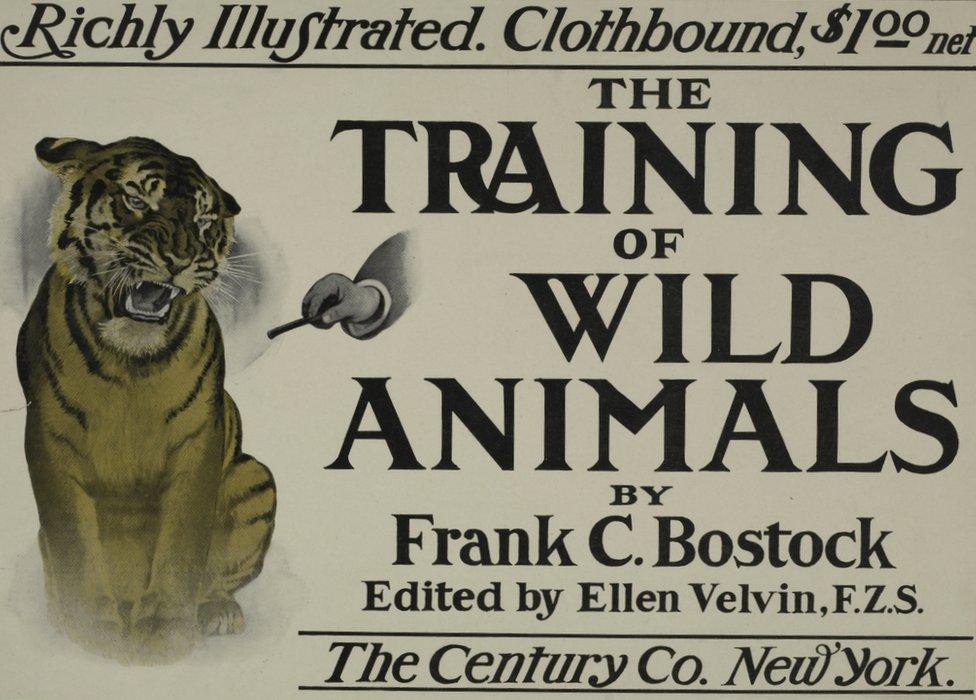

Frank C Bostock published a volume of his memoirs and training tips

Reaching Birmingham, Bostock and his team were preparing for a show when one of his lions jumped over its keeper, pushed through a rip in the circus tent, and prowled off towards Birmingham city centre "as free and untrammelled as when in his native wilds".

According to Bostock's account of it it his book The Training of Wild Animals, external, the lion came across one of the openings to the sewerage system and "down he sprang, looking up at the crowd of people and roaring at the top of his voice. As he made his way through the sewers, he stopped at every man-hole he came to, and there sent up a succession of roars, driving some people nearly wild with terror."

Large crowds had gathered, eager to see the menagerie. Understandably, with a lion on the loose, they started to panic.

So Bostock came up with a plan.

Crocodiles were seen as a quirky pet for Victorian ladies

Other escapes from menageries

In 1851 a tapir broke out of its den at Wombwell's menagerie in Rochdale, causing panic among the spectators.

In 1867 a rattlesnake escaped from its box in Mander's menagerie, killing a horse and a bison.

In 1868 five leopards escaped from a menagerie in the Scottish borders after their caravan overturned on the road.

In 1883 a bear got loose in Grimsby and entered a private house.

Even elephants sometimes went missing, though they could usually be found in the vicinity of the nearest pub. In 1854 an elephant disappeared from Batty's menagerie in Holyhead and was gone for nearly 24 hours. It was eventually discovered in a hotel cellar, surrounded by empty wine bottles.

Source: Dr Helen Cowie

Bostock toured the world with his menagerie

Rather than try to quell the volatile crowd, he put a second lion in a cloth-covered cage and sneaked it out on the back of a lorry.

He then returned, blowing his horn to attract attention, with the lion clearly visible.

In his own words, "everything went off well".

People fell for the ruse and he was cheered as a hero. "A shout went up from the crowd 'They've got him! They've got him! They've got the lion!'"

His actions in apparently getting the lion from the sewer were reported around the world.

A New Zealand newspaper ran an article called "A lion at large in Birmingham: How the King of the Forest was recaptured" which included details such as "the keeper's attention was momentarily distracted by a fight between an ostrich and a deer" and "a group of children were in the lion's path. It cleared them at a bound".

The publicity worked in Bostock's favour. Hordes of people attended the show that evening, blissfully ignorant of the fact a man-eating lion was prowling beneath the streets.

Bostock said he "was in a perfect bath of cold perspiration, for matters were extremely serious, and I knew not what to do next. Fortunately, the lion had stopped his roaring, and contented himself with perambulating up and down the sewer".

On the afternoon of the following day, the chief of police of Birmingham visited the menagerie and congratulated Bostock on his "marvellous pluck and daring".

Bostock came clean.

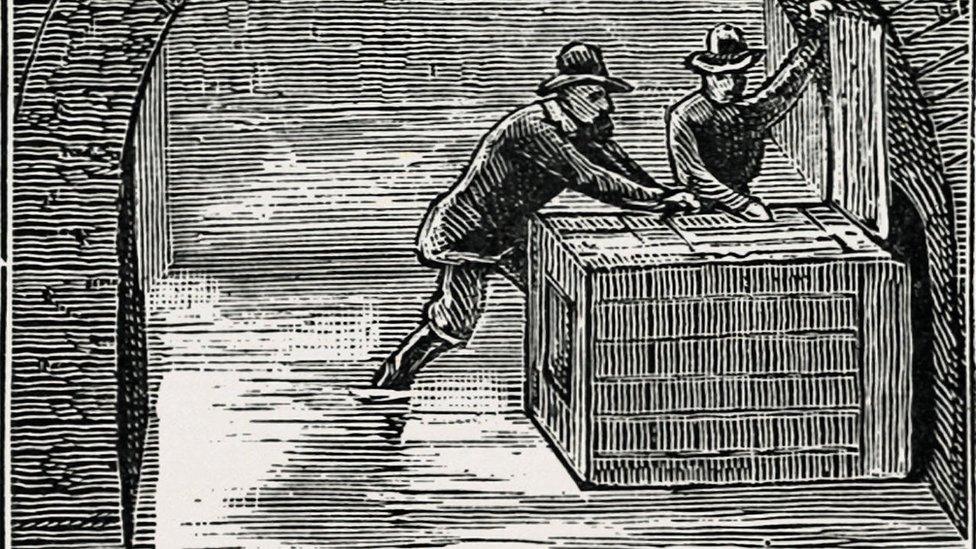

Illustration of men putting a cage over a manhole in an attempt to trap the lion

"I shall never forget that man's face when he realized that the lion was still in the sewer, it was a wonderful study for any mind-reader," he reflected.

"At first he was inclined to blame me but when I showed him I had probably stopped a panic, and that my own liabilities in the matter were pretty grave possibilities to face, he sympathized with me, and added that any help he could give me, I might have.

"I at once asked for 500 men of the police force, and also asked that he would instruct the superintendent of sewers to send me the bravest men he could spare, with their top-boots, ladders, ropes, and revolvers with them, so that should the lion appear, any man could do his best to shoot him at sight. We arranged that we should set out at five minutes to midnight, so that we might avoid any crowd following us, and so spreading the report.

"At the appointed time, the police and sewer-men turned out, and I have never seen so many murderous weapons at one time in my life. Each man looked like a walking arsenal, but every one of them had been sworn to secrecy."

This secrecy was preserved until Bostock himself spilled the beans.

An illustration of a man and the lion in the sewer

It was more than 24 hours after the stooge lion was paraded that Bostock, now in the sewer, "saw two gleaming eyes of greenish-red just beyond, and knew we were face to face with the lion at last".

Bostock and his gang of men chased the lion through the sewers by scaring it with shouts and fireworks.

When face-to-face with the lion Bostock took off his boots and put them on his hands "and going up close to the lion, was fortunately able to hit him a stinging blow on the nose. Fearing that he would split my head open with a blow from one of his huge paws, I told one of my men to place over my head a large iron kettle which we had used to carry cartridges and other things to the sewer".

But the kettle fell off his head and startled the lion which "turned tail like a veritable coward" and ran into a rope lasso laid out ready to ensnare him.

Bostock's recounting of the story in his memoirs concludes, rather smugly, with: "I got the lion out of the sewer, as the people of Birmingham supposed I did, only their praise and applause were a little previous."

He died aged 46 in 1912, not by the paw of a justifiably-annoyed big cat but from the flu. There's a docile-looking stone lion on his grave.

Frank C Bostock's grave is in Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington