Clive Sullivan: The man who broke rugby's racial barrier

- Published

Clive Sullivan led Great Britain to rugby victory in 1972

It is 45 years since Clive Sullivan led the nation to Rugby League World Cup victory. On the day the 2017 tournament kicks off, BBC News looks at how as captain of Great Britain he helped break down barriers.

When the 18-year-old Welsh winger joined Hull FC in 1961, there were very few black men in prominent sporting positions.

But scoring a hat-trick in a trial game with the team certainly put Sullivan on the map and he signed a contract the following day.

So began a career that 11 years later, in 1972, would see him raise the Rugby League World Cup trophy as Great Britain captain - the last occasion the trophy was won by any nation other than Australia or New Zealand.

Clive Sullivan won the Challenge Cup with Hull KR (left) in 1980 and Hull FC (right) in 1982

"Sullivan's appointment [as captain] was extraordinary for the time," said Martin Polley, director of the International Centre for Sports History and Culture at De Montfort University.

"A few professional football teams had black players by this time, like Clyde Best at West Ham.

"But the England football team were six years away from even picking a black player for the senior team.

"There were some exceptions in boxing and cricket, but not many had made it through."

James Oddy, author of a new biography on Sullivan, described him as a "pioneer in the social history of British sport".

"Clive did a lot for how society judged black athletes, he blazed a trail.

"One of his heroes was Muhammad Ali and perhaps that meant he was more aware than you might have thought about his role.

"Above all, he was a true professional."

Sullivan's talents as a try-scorer saw him play for several teams

Yet Sullivan's success did not bring national attention. After the team won the World Cup in France, it was a low-key return.

With £50 in his pocket for winning the tournament - about £600 in today's money - he went back to work at an aircraft factory in Brough, though he did take the trophy in for workmates to see.

"When Clive came home with the team there were no reporters waiting at the airport to greet them," remembered his wife, Rosalyn Sullivan.

"They slipped back into normal lives."

The team's return was something of a "damp squib", according to Mr Oddy.

But the absence of the red-carpet treatment might be down to the fact most rugby league players at the time were "just ordinary working men".

They played professionally on a part-time basis and worked alongside training and playing. Sullivan himself worked in several factories, a building society and managed a sports trophy shop.

Sullivan played professionally part-time while working in factories

His impact on the sport, however, would be lasting - breaking down barriers in rugby league and in his adopted city of Hull where he had an impact on the "colour thing", Mrs Sullivan said.

She said when racism was directed at the young couple, they dismissed it as ignorance and "the way of the world".

"Comments were made behind our backs but Clive dealt with it in his own way.

"He was very comfortable in his own skin and was very proud of being black and being Welsh.

"He [made] people understand he was just a person like anyone else. He was very humble."

Johnny Whitely, who made more than 400 appearances for Hull FC, credits Sullivan with unifying a city split by the river and its two rugby league sides.

"He would have been a modern sporting superstar, I am sure of it," he said.

"Being black he would also perhaps have had that much publicity as a role model too, as he had such a gentlemanly attitude in life."

Henderson Gill said Sullivan paved the way for players like him

Sullivan, who played with distinction for both Hull FC and Hull KR, also had an influence on the next generation of black rugby league players.

Henderson Gill, who played rugby league for Wigan and Great Britain during the 1980s, described Sullivan as the "son of Hull".

"Clive was one of the guys that paved the way for players like me. He was one of my heroes."

During Sullivan's 20-year career, a growing number of black role models also started to feature in other sports, including John Conteh and Neville Mead in boxing, Sonia Lannaman and Tessa Sanderson in athletics, and numerous football players at West Bromwich Albion, said Prof Polley.

"On the down side, there was also more blatant racism - manifested most obviously in terrace chants and banana-throwing at some football grounds," he added.

Of course discrimination has long been part of sporting life, said Dr Katy Sian, lecturer in sociology at the University of York.

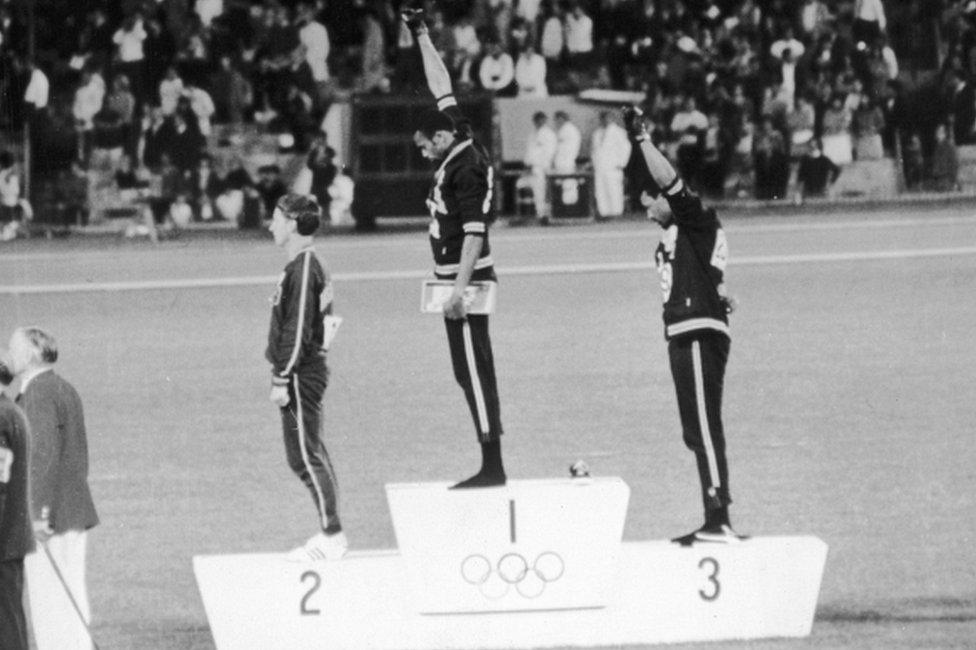

During Sullivan's career, perhaps the most high-profile stand against discrimination was staged by the US athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos with their "Black Power" salute at the medal ceremony for the men's 200m at the 1968 Mexico Olympics.

Black athletes at the 1968 Mexico Olympics raised a gloved fist in a silent protest

"It is often said that politics and sport shouldn't be mixed," Dr Sian said, but examples such as this "show us the politicised nature of sport".

"This form of resistance continues today, for example NFL players campaigning to "take a knee".

"[But] outshining in a sport can be another key way to disrupt the wider politics of racism, by bringing into question ideas about nation, identity and belonging.

"Think of Mo Farah, Usain Bolt and Muhammad Ali - that is incredibly inspiring for people of colour to see sports players rising to the top."

Sullivan was not a household name in the way his successors have become. But he was not entirely ignored by the establishment.

He was appointed MBE for services to rugby league and even featured on the high-rating TV series This is Your Life after the 1972 World Cup victory.

In 1980, he won the Challenge Cup with Hull KR, then again with Hull FC in 1982, finally retiring in 1985 to take over a social club with his wife.

One of the main roads into Hull was named after the rugby player

But within months he was diagnosed with liver cancer and he died in October the same year, aged 42.

At his funeral, crowds lined the streets outside Hull Minster and thousands of pounds were raised for cancer research in his name, Mr Oddy said.

In his honour, the main road into Hull from the west was named Clive Sullivan Way and the sign bearing his name is still one of the first things visitors see on the approach to the city.

"I don't think he appreciated how good he was. People liked him as a person not just a rugby player," his wife said.

"I'm sad he did so much and yet never really made a really good living from the game - it was all done for love."

Clive Sullivan's career

Born 9 April 1943 in Splott, Cardiff - died 8 October 1985 in Hull

Played 17 times for Great Britain, captaining the world cup-winning team in 1972, and 15 times for Wales

Played in three world cup finals

For Hull FC: A try-scoring record of 250 tries in 352 appearances including seven tries in one game v Doncaster in 1968

For Hull Kingston Rovers: He scored 118 tries in 213 matches

The only man to score a century of tries for both clubs

Won the Challenge Cup with Hull KR in 1980 and Hull FC in 1982

Also played for Oldham and Doncaster