How Alan Pegler saved Flying Scotsman for the nation

- Published

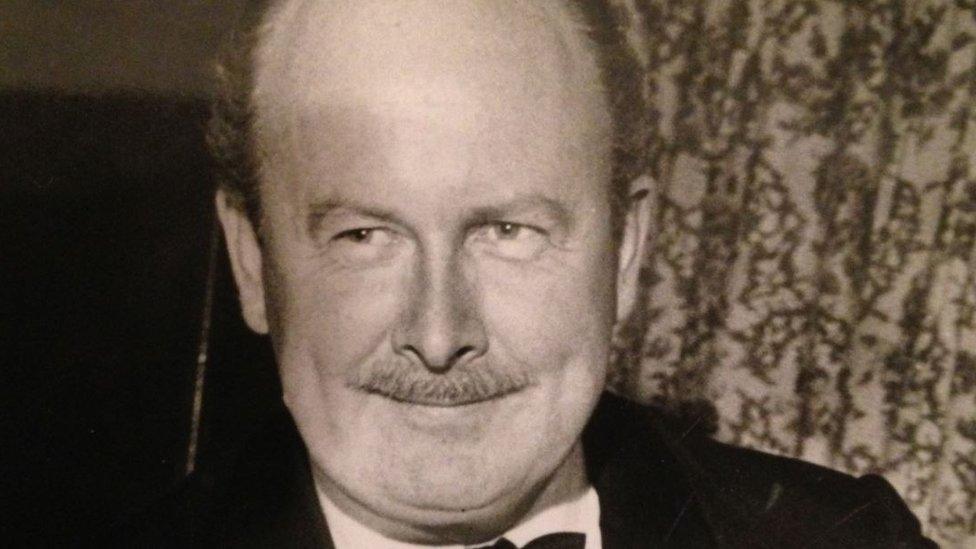

Alan Pegler fell in love with the locomotive at the age of four

Just over half a century ago, the world's best-loved steam engine was destined for scrap. That it was saved was down to the efforts of one man - a true British eccentric. But his love for the locomotive he called the "old girl" cost him his fortune - and nearly saw Flying Scotsman stranded in the United States.

Alan Pegler was four when he was taken by his parents to the British Empire Exhibition of 1924.

As he walked through pavilions full of exhibits, one left the young boy dazzled: LNER 4472 Flying Scotsman.

"I was lifted into its cab," he said in an interview with the Railway Magazine.

"I remember being impressed at how clean it was, compared with the grimier engines we saw at home, and how marvellous its apple-green paint was.

"I was spellbound and couldn't stop thinking about it all the way home."

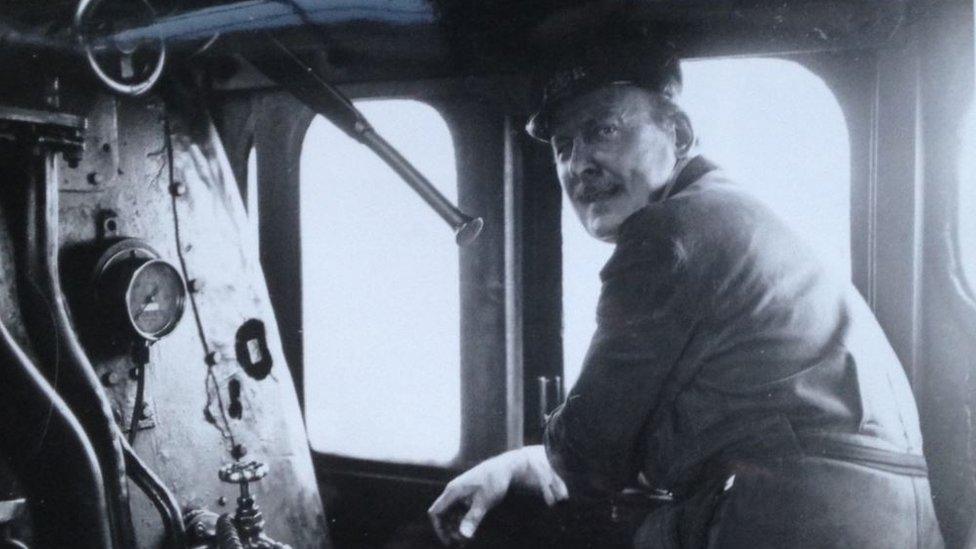

In 1963, the advent of diesel meant Flying Scotsman looked destined for the scrapyard

Pegler's infatuation with the first British steam locomotive to break the 100mph barrier and run non-stop from London to Edinburgh would become a lifelong love.

Forty years after this encounter, he became instrumental in saving it from the scrapyard.

His daughter Penny Vaudoyer can remember the day, in January 1963, when her father came into her room to tell her he had bought the engine.

"He had a little sparkle about him," she said.

"He sat down on my bed and said, 'I've bought a steam engine. I'm going to have her painted apple-green [again] and we are going to have so many wonderful adventures with her'."

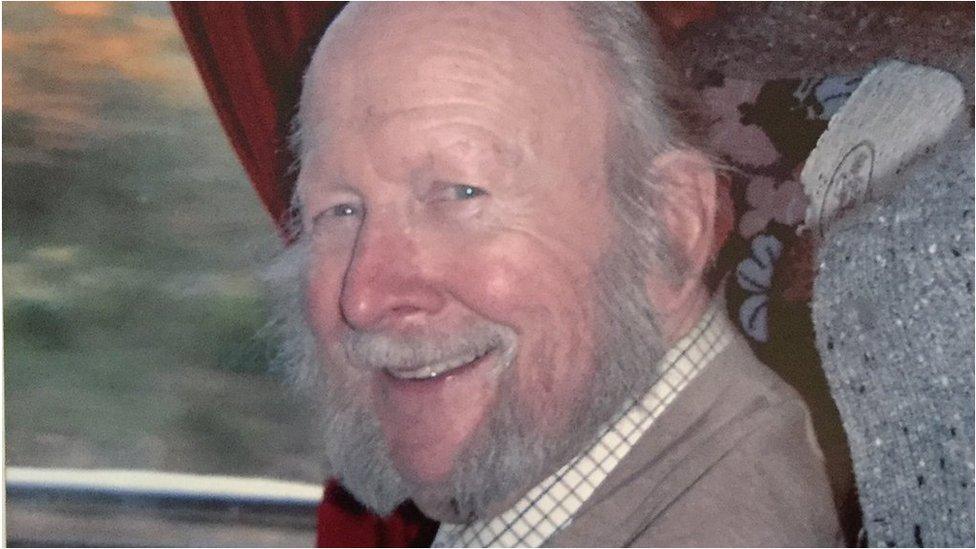

Penny Vaudoyer can remember her father having "a little sparkle" about him when he bought the engine

Pegler was an eccentric raconteur. Born into a family of manufacturers in Retford, Nottinghamshire, he spent his childhood playing at being a porter at his local station at Barnby Moor, watching the trains go by on the Great Northern mainline.

Aged 17, he gained his pilot's licence and spent his time flying over the line, chasing steam locomotives. Such experience saw him posted into the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm during World War Two. He later became a dive-bomber and survived a horrific crash landing when his engine cut out.

"He was a swashbuckling buccaneer of a character," said Andy Roden, editor of Steam World and author of a book about Flying Scotsman. "He was just going to do what he wanted and, thankfully for us steam buffs, that mostly involved the railways."

"Like many of that generation, his character was shaped by World War Two," added Bob Gwynne, associate curator at the National Railway Museum. "After he'd been through that, there was nothing he couldn't bounce back from."

Pegler found himself a very wealthy young man

After the death of Pegler's father in 1957, there was a feeling among his relatives that he was becoming too diverted by his rail "hobby" to take on the family business.

By that stage, he had a seat on British Railways' Eastern Area board and had reopened a narrow-gauge line in Wales: the Ffestiniog, in Gwynedd.

"The family got fed up with him being more interested in railways than the business and bought him out for £70,000," said Mr Roden.

"It was a huge amount of money at that time and it was burning a hole in his pocket. Most of us would think, 'Let's retire and live the life of Riley'."

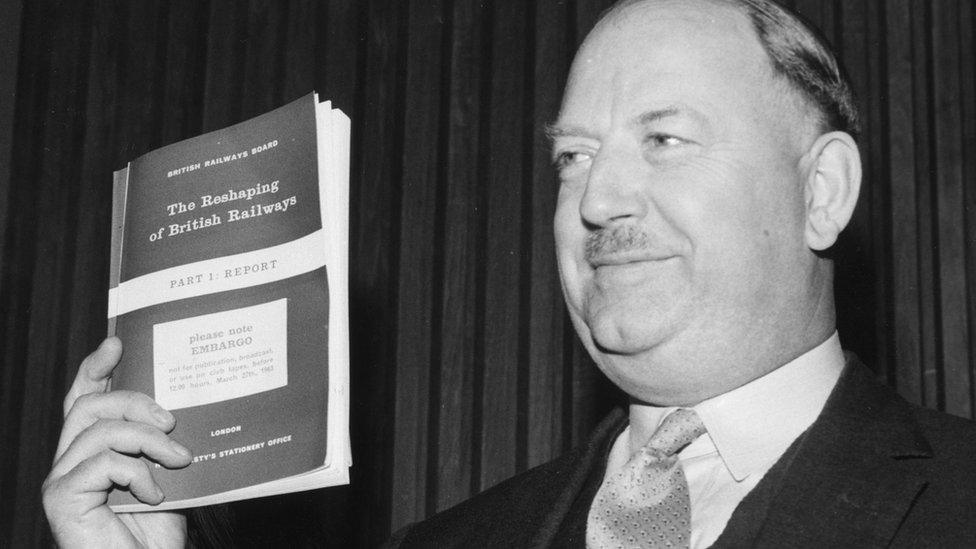

Dr Richard Beeching was infuriated by Pegler's publicity campaign for Flying Scotsman

Instead, Pegler became swept up in a debate that was engulfing Britain - the future of steam railways.

British Railways (BR), the nationalised body that had taken over Britain's ailing post-war rail network, was determined to replace steam with diesel.

Its chairman Dr Richard Beeching believed the move would save money and, as a result, thousands of steam engines were culled.

In response to the outcry, BR decided to preserve a few locomotives. However, Flying Scotsman was not among them.

Pegler negotiated a "fantastic deal" when he bought the locomotive

BR seemed to feel only a few engines per designer could be preserved. Instead of Flying Scotsman, the board chose to save the record-breaking Mallard which was also the work of influential railway engineer Sir Nigel Gresley.

"BR had already saved Nigel Gresley's best design, which was Mallard," said Mr Gwynne. "They didn't need another one.

"Flying Scotsman would certainly have been scrapped. Her future looked bleak."

When Pegler found out Flying Scotsman wasn't going to be saved for the nation, he was aghast.

"He felt its destruction would be a huge loss," said Mr Roden.

"Pegler decided on the spot to buy it for £3,000 and negotiated for himself a fantastic deal."

You might also be interested in:

As well as ensuring the engine got a complete overhaul and its own shed, Pegler was able to charter trains for Flying Scotsman. By 1968 it had become, Mr Roden says, the only steam locomotive running on Britain's railways.

"He saved a national icon at a time when the nation didn't actually want to save her," he said.

The day Blue Peter's John Noakes rode Flying Scotsman

Pegler ran Flying Scotsman very successfully at first.

"He was a master at publicity," said Mr Gwynne. "He paid for the services of a London-based PR firm and over the next few years Flying Scotsman became the most famous locomotive in the world."

Thousands turned out to see the engine everywhere it went. It appeared on BBC children's programme Blue Peter, with presenter John Noakes shovelling coal in the cab.

"A lot of change was going on and people were nostalgic for the past. And the media love eccentrics, especially rich ones," said Mr Gwynne.

"Pegler played on that very well and he had the time of his life."

The publicity campaign ensured the engine attracted worldwide attention

In 1968, in a stroke of genius, Pegler managed to recreate the engine's famous non-stop 1928 trip from London to Edinburgh.

"The BBC hired a helicopter to cover it," said Mr Roden. "The significance was that it was the last time steam was going to be able to do that.

"It was a remarkable swansong and Pegler was in the cab, in the buffet car, all over the place."

But all the fuss about Flying Scotsman would bring Pegler into confrontation with Dr Beeching.

"The poor man was trying to modernise the railway and there was this steam engine getting all the headlines," said Mr Gwynne. "Beeching was not very happy."

Pegler was sacked from the BR board.

"There's a story that he asked Beeching whether he was being dropped because of Flying Scotsman," said Mr Roden.

"Beeching sat back in his chair and looked Pegler straight in the eye. After a pause, he said, 'Yes'."

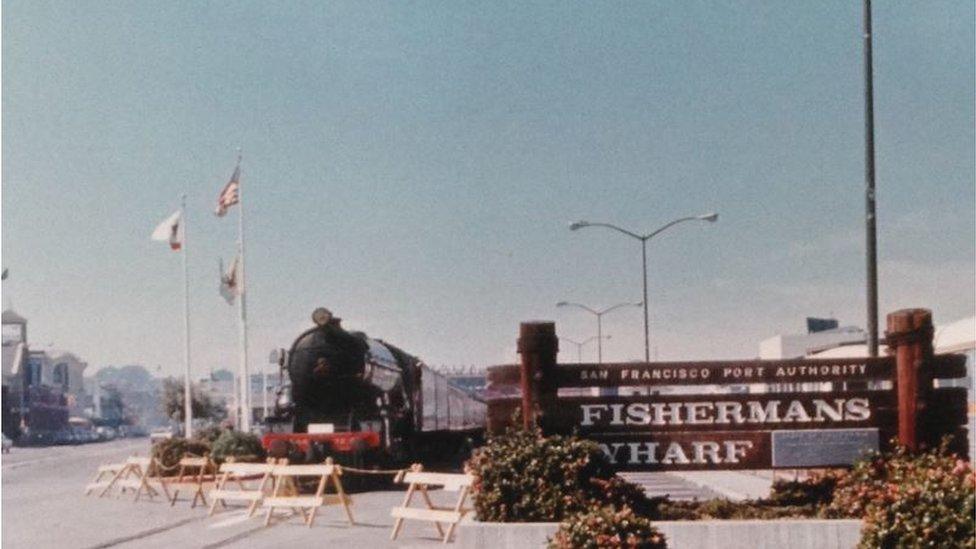

In the late 1960s, the "old girl" went on a tour of the United States

Undeterred, Pegler set his sights on the United States, where he led a promotional tour in 1969 in conjunction with the British government.

At first, it was a resounding success.

"Amazingly, at the time of the space race and the moon landings, there was a nostalgia for the past," said Mr Roden. "The Americans came to love Flying Scotsman almost as much as we do.

"There was an elegance and a romance associated with her and her name that sums up exactly what she's about."

Eventually, the government decided to call time on the tour. For Pegler, the urge to soldier on alone proved irresistible.

"A chap said to him, 'it's your goddamn locomotive - why don't you drive it?" said Mr Roden.

"That was something you could do in the US, and Pegler, being the character he was, did. He thought it might result in him going bankrupt. But it was a once-in-a-lifetime chance."

Despite his initial success, Pegler ended up penniless in San Francisco

The consequences of his decision to carry on with the tour proved disastrous. His daughter, who was 17 at the time, remembers travelling on the cash-strapped second tour.

"It was an almost unbelievable journey," Mrs Vaudoyer said. "We crossed the Rockies and went from Montreal, all the way to San Francisco through all this wonderful landscape. Even in the small towns we had big welcomes.

"I could tell things were getting difficult for my father though. By the end of the trip, we weren't staying in nice hotels any more - we were sleeping in sleeping bags in the carriage. But it was still great fun."

Pegler would end up filing for bankruptcy in the UK.

"Financially, he lost it," said Mr Roden. "The tour became like a travelling circus. Business dried up and Pegler ran out of money.

"He sat on his suitcase on Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco and thought, 'what on earth am I going to do next?'"

For his beloved engine, the future seemed equally bleak. Flying Scotsman was parked in an army base in California. There was great national anxiety she would never return to British shores.

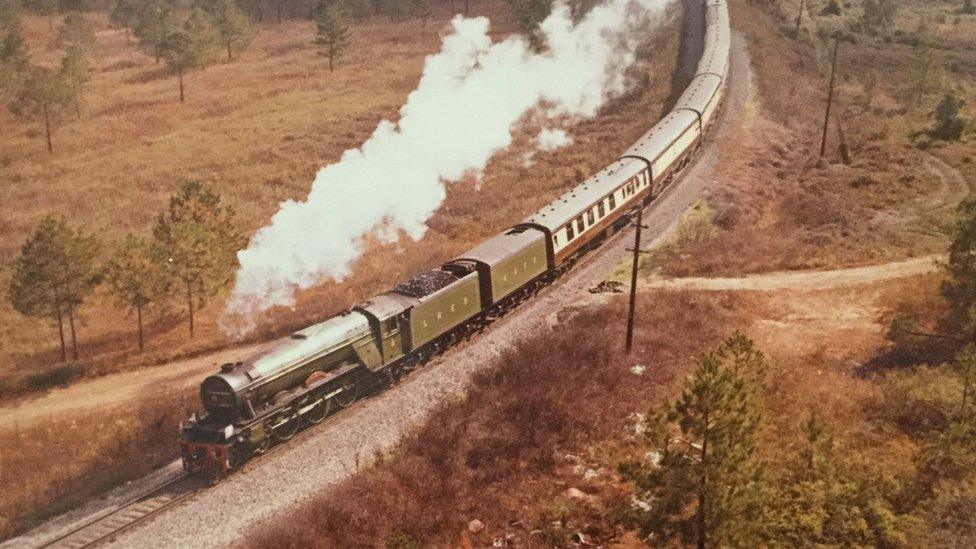

Crowds remain captivated by the famous green engine

But both Pegler and his "old girl" proved equally indefatigable.

William McAlpine, another wealthy businessman with a passion for railways, stepped in to buy the locomotive and bring her home.

"It was absolutely mobbed when it came back. She had acquired superstar status," said Mr Gwynne.

As for Pegler, who married four times, he became a shipboard entertainer and worked his passage back to the UK.

"I would sing my heart out," he told the Railway Magazine. "The drinkers would pass round the hat and I would have enough for a meal the next day."

Despite the loss of his fortune, Alan Pegler bounced back

Back home in Britain, he embarked on a career as an entertainer and actor, including a spell as a Henry VIII impersonator at a restaurant in London - his mutton chop whiskers and extrovert personality proving perfect for the job description.

Today Flying Scotsman sits in the National Railway collection, having been bought in 2004. As for Pegler, who died in 2012, he always remained in love with the engine that ruined him financially.

"My father's passion for 'the old girl' lasted all his life, right up until he died," recalled his daughter.

"He always travelled behind her whenever he had the opportunity. She was part of the family."

But many feel he deserves to be better remembered for his achievement in preserving a national icon.

Today Flying Scotsman is safely preserved in the national collection

"His finest hour was saving Flying Scotsman," said Mr Roden.

"He is one of the catalysts of the railway preservation movement. If you had said 50 years ago that steam locomotives would still be being built and lines reopened, people wouldn't have believed you.

"The starting point for all that goes back to people like Alan Pegler."

- Published21 May 2017