England v immigration: A millennium of fears condensed

- Published

The Windrush scandal and the 50th anniversary of the "Rivers of Blood" speech are just the latest reminders that the issue of immigration to the British Isles is a fraught one. For centuries it has prompted debate - and also anger, fear and even murder.

You might say it started well. A Greek explorer in about 320BC described the locals as "especially friendly to strangers".

This was perhaps a good thing, as over the centuries there were waves of invasions, by Romans, Saxons and Vikings.

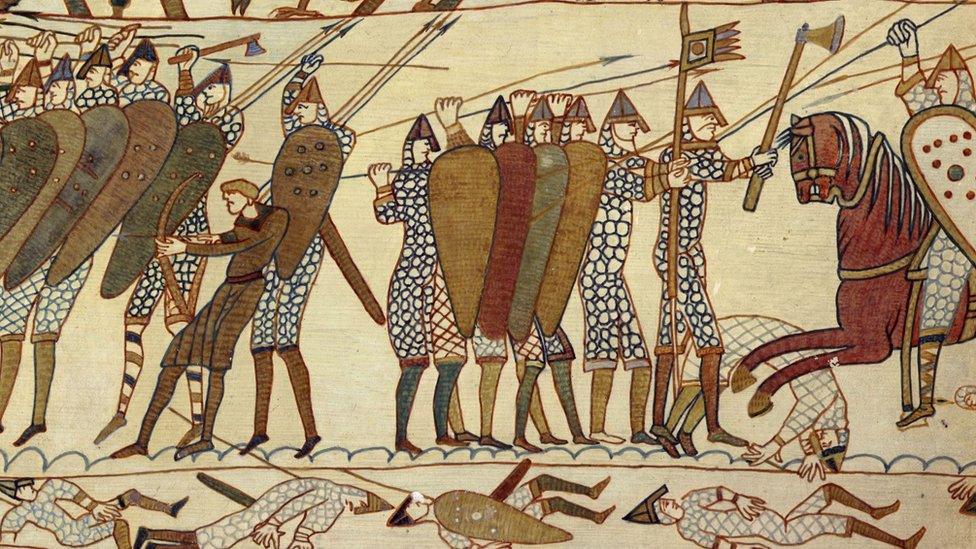

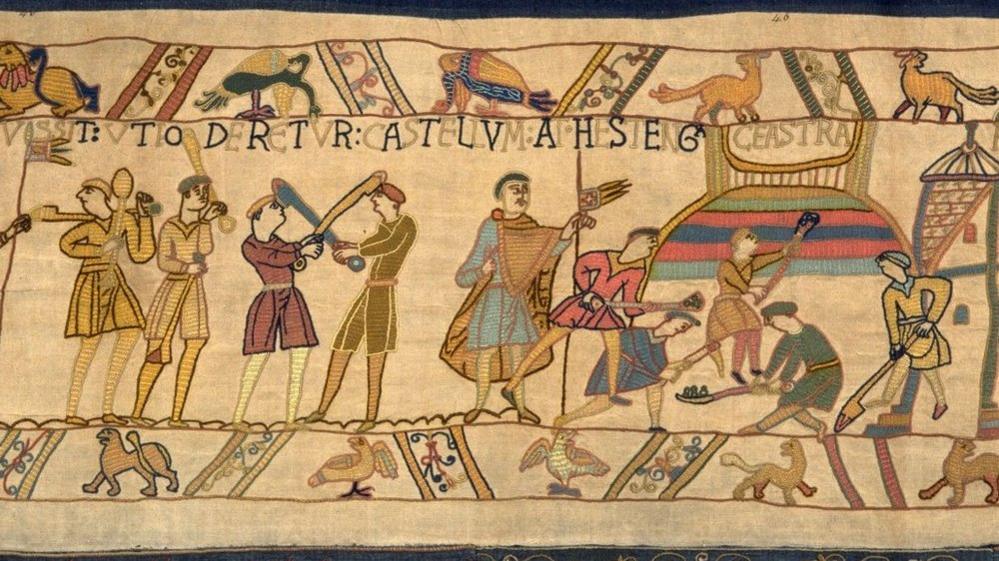

For the Anglo-Saxons, the Norman Conquest started badly and then went downhill

After hundreds of years of treaties and battles, it was a Danish-flavoured Anglo-Saxon kingdom that faced the Normans in 1066. And lost.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle weeps at how the new King William divided up the land to his foreign nobles: "[He] let it go into the hands of the man who offered him most of all, and did not care how very sinfully [they] got it from wretched men, nor how many unlawful things they did; but the greater the talk about just law, the more unlawful things were done."

Arriving not long after William, in about 1070, the Jews were one of few groups allowed to lend money.

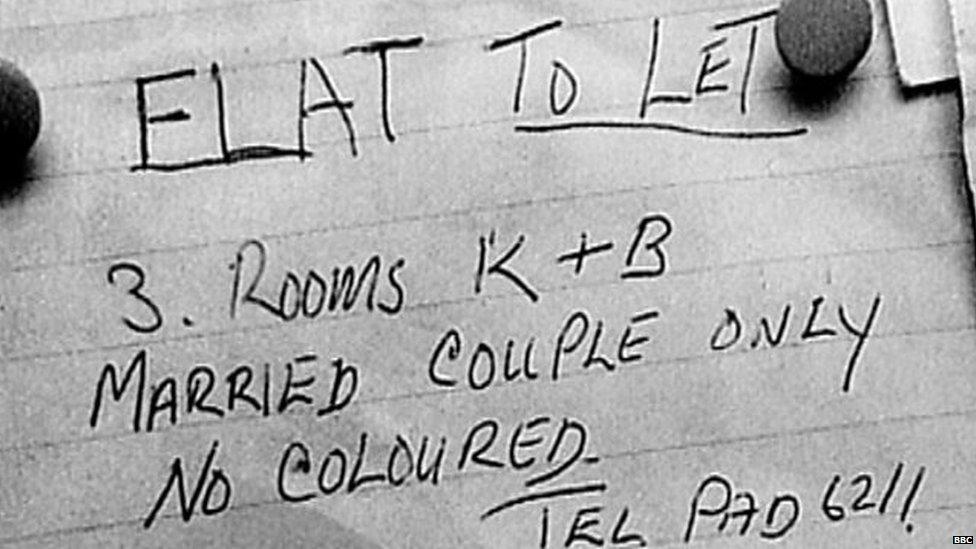

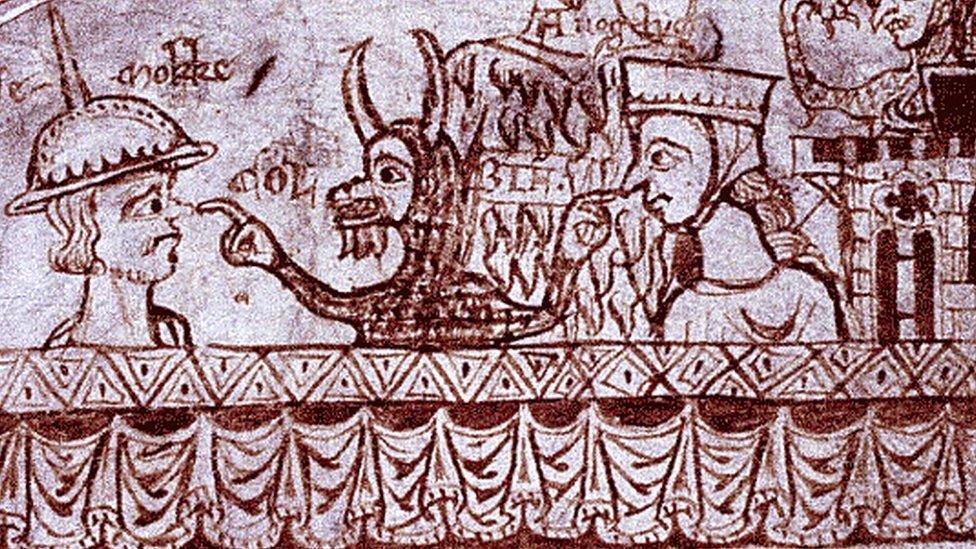

A drawing on an official tax document shows bitter resentment towards the Jews

One estimate says they made up 0.25% of the population but controlled a third of the coinage, external.

This, combined with religious bigotry, led to resentment.

After the 1144 murder of a boy in Norwich, there were attacks on the local Jewish community.

The monk and writer Thomas of Monmouth fanned the flames by claiming it was a ritualistic murder: "[The Jews] next laid their bloodstained hands upon the innocent victim, and having lifted him from the ground and fastened him upon the cross, they vied with one another in their efforts to make an end of him."

Jewish people at one point had to wear badges and hats to make sure they could not blend in

The blood libel - that Jews killed Christian children for ritualistic reasons - was born.

In York, in 1190, about 150 Jews killed themselves after being besieged by a mob. In 1255, 18 Jews in Lincoln were executed, others vanished, after another mystery death, and in 1264 a rumour that the Jews of London were plotting against t he city saw hundreds killed.

In 1278, nearly 700 were arrested for alleged counterfeiting and perhaps as many as 300 were executed.

While condemning such massacres, contemporary writer William of Newburgh claimed: "The Jews... had impudently puffed themselves up against Christ and inflicted very many burdens on Christians."

After decades of attacks, high taxes and restricted rights, the entire community, between 5,000 and 15,000 people, was expelled in 1290. The ban would not be lifted for 360 years.

The Black Death killed tens of millions and caused a labour crisis across Europe

Besides being a small, damp island on the edge of the known world, by the 1350s, the nation had another problem.

As Prof Mark Ormrod, from the University of York, points out: "England was almost deserted. The Black Death had wiped out about half the population, leaving it with two to three million inhabitants.

"England had to find a workforce."

The financial gap left by the Jews was filled by Italians - and soon they too were in the firing line.

In 1376 there was a move to throw them out of England as they were just "Juys, & Sarazins and privees Espies" and furthermore had introduced "un trop horrible vice" - sodomy.

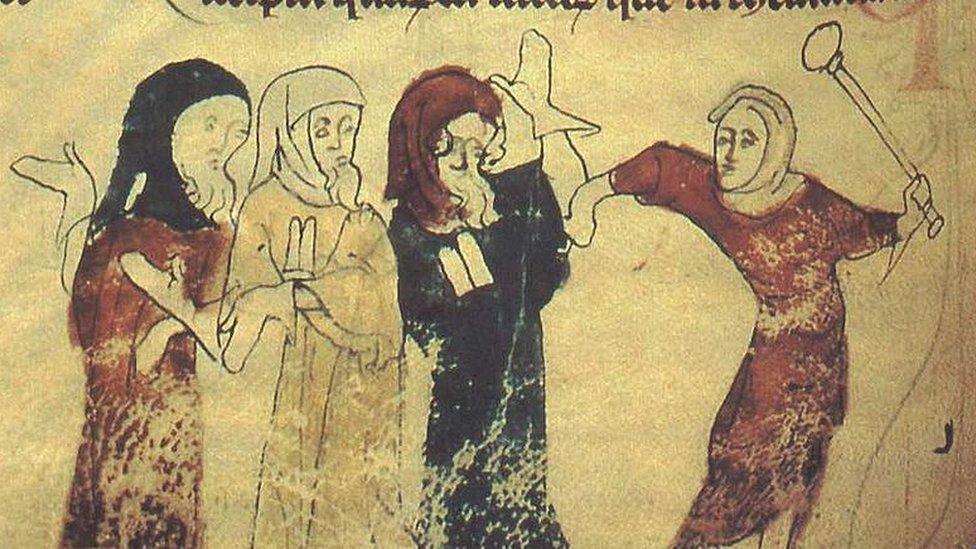

As well as attacking officials, some taking part in the Peasants' Revolt targeted foreigners

Monarchs and governments had a difficult balancing act: the skills and tax income that immigrants provided were desirable, while dealing with the public hostility they aroused was not.

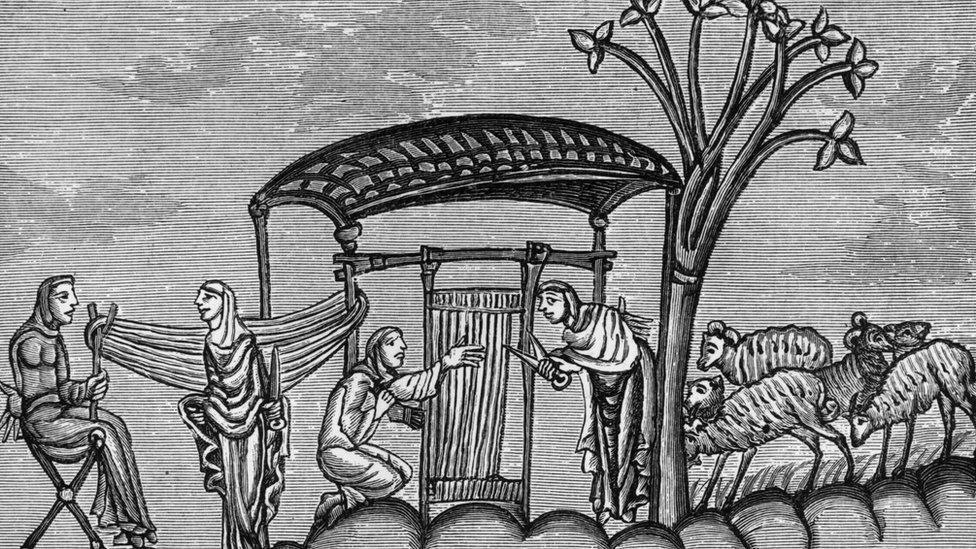

Wool was medieval England's top industry and about 1,000 expert Flemish weavers were in London by the mid-14th Century.

In 1378 London weavers demanded control of the Flemish, saying they were "for the most part exiled from their own country as notorious malefactors".

English wool - and the cloth that came from it - was one of Europe's most desirable commodities

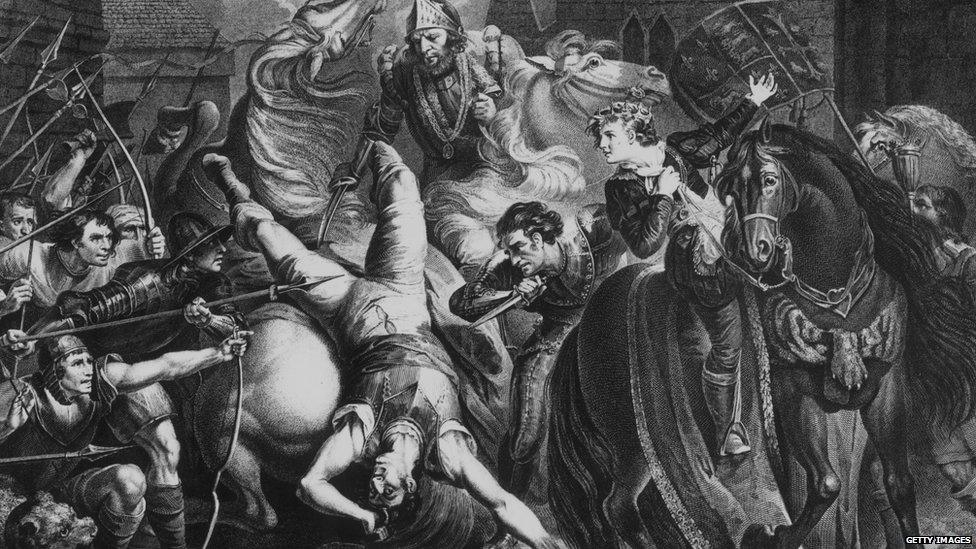

This was bloodily expressed during in the 1381 Peasants' Revolt when about 40 were dragged from a church and subjected to a language test.

As witnesses described it: "And many Flemings lost their heads at that time, because they could not say 'bread and cheese' but 'brode en case'.".

Prof Ormrod says: "For many people nationality was simple: you were either born in England, or you weren't. Foreigners were sometimes treated as a single, undifferentiated whole.

"But formal records before the 16th Century almost never made direct reference to the colour of anyone's skin."

Richard III was certainly no friend to the immigrant

Venetian ambassadors to England in the 15th Century were "perplexed by the English - especially by their extreme hostility to foreigners".

A 1440 tax survey of aliens indicates they made up 2% of England's population - reaching 10% in London and Bristol.

In his brief but turbulent reign, Richard III stamped down hard. In 1484, the last Plantagenet monarch banned skilled tradespeople or merchants from entering England, while those already resident were barred from employing anyone except their own family.

As Prof Ormrod says: "The clear intent of this statute was to starve out skilled foreign workers.

"The public defence of such a radical position was that honest English people were at risk of losing employment and becoming 'thieves, beggars, vagabonds and people of vicious living, to the great disturbance of Your Highness and of your whole realm'."

Hostility wasn't just reserved for skilled foreign workers.

Gypsies aroused a mix of fascination and fear

Gypsies moved across Europe during the Middle Ages, sometimes claiming to be eastern aristocracy.

Tudor England initially viewed them as exotic "Egyptians" or "Rowmais". The honeymoon did not last.

In 1530 Henry VIII forbade Gypsies from entering England, saying they "many times, by craft and subtlety, have deceived the people for their money; and also have committed many heinous felonies and robberies, to the great hurt and deceit of the people".

In 1554 Queen Mary made repeat offences punishable by death.

Five decades later, the writer Thomas Dekker described gypsies as "beggerly in apparell, barbarous in condition, beastyly in behaviour... a people more scattered than the Jews, and more hated".

The St Bartholomew's Day massacre in Paris brought a wave of Protestant refugees to England

A flow of Protestant refugees, known as Huguenots, external, escaping religious wars on the continent, became a flood after the St Bartholomew's Day massacre in Paris in 1572.

Many locals were unimpressed.

"They are a commonwealth within themselves", complained one. "They keep themselves severed from us in church, in government, in trade, in language and marriage."

Prof Ormrod says: "The issues were around national security, the protection of the economy and religious culture.

"Parliament constantly debated whether allowing foreigners to live in the country was a security risk, how much they made from the English economy, and how to classify them."

Black people were present at many levels of Tudor society

The fact "strangers" were subject to double taxes and limited property rights did not evoke much sympathy.

In 1593, posters appeared complaining of the "beastly brutes the Belgians, faint-hearted Frenchmen and fraudulent Flemings" who were permitted by Queen Elizabeth, it was claimed, "to live here in better case and more freedom than her own people".

The authorities suppressed this discontent, but were not above scapegoating.

Black people might have numbered only about 1,000, but Elizabeth moved to expel them in 1596, saying "there are of late divers blackmoores brought into this realm, of which kind of people there are allready here to manie".

Although often penniless, the Huguenots brought technical skill and a strong work ethic

A second wave of Huguenots fled in France in the 1680s, with up to 50,000 coming to England. A popular song complained: "The nation it is almost quite undone, by French men that doe it dayly overrune".

But these incomers were, on the whole, skilled and educated. Many prospered.

The next influx not only shocked the nation but torpedoed an early attempt at a liberal immigration policy.

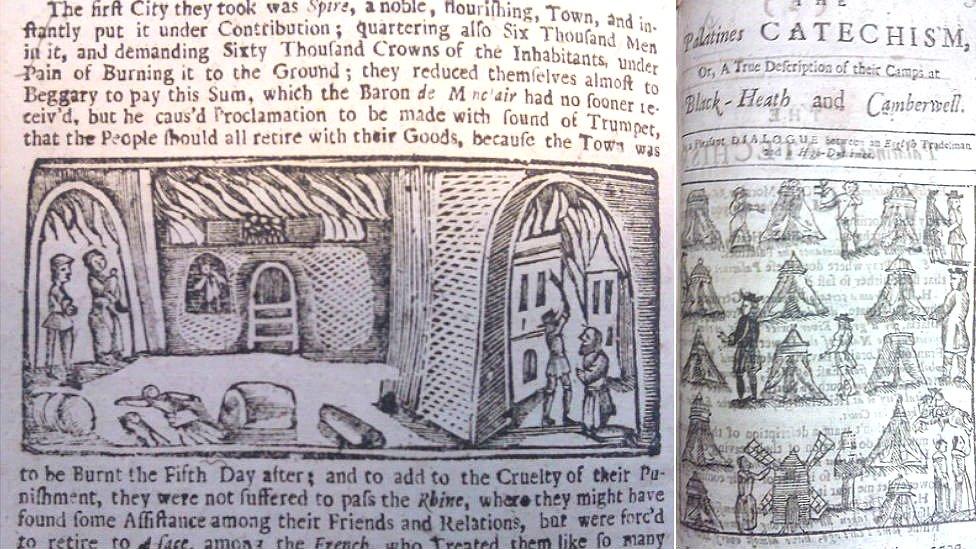

In 1708 leaflets had raised sympathy for German Protestants - "Poor Palatines" - caught up up in new religious wars.

Pamphlets told of the Palatines' persecution and difficult living conditions

The first boatloads - about 900 people in all - were given food and supplies, but an estimated 13,000 landed within months, overwhelming the feeble 18th Century infrastructure.

Donations raised thousands of pounds but most of these new arrivals were housed in army camps on Blackheath.

Rumours soon swirled of German gangs attacking locals, amid claims many were not even Protestants.

One pamphleteer described them as "as parcel of vagabonds, who might have lived comfortably enough in their native country, had not laziness of their dispositions and report of our well-known generosity drawn them out of it".

Some were sent to marginal farmland in another strife-torn part of the British Isles - Ireland.

The Irish were lampooned as violent drunks, a view that affected policy towards them

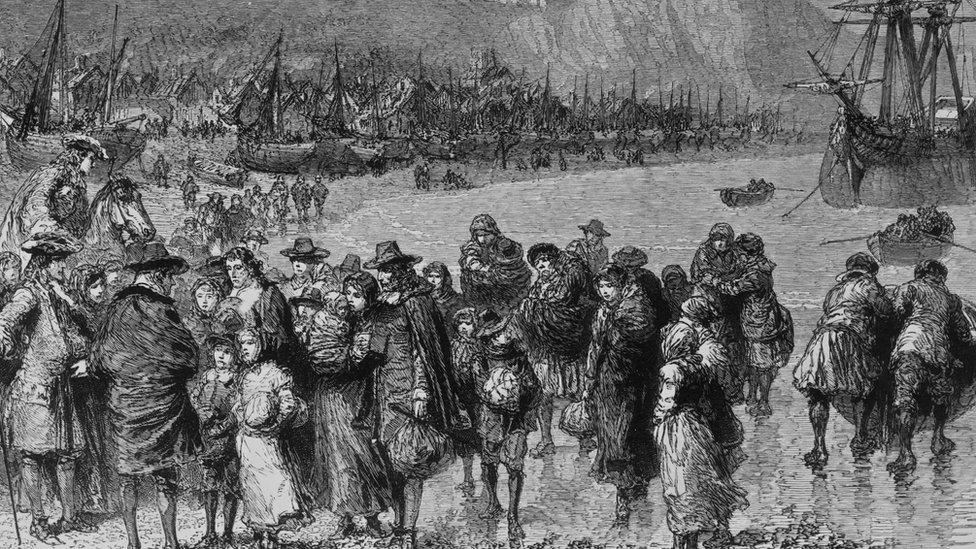

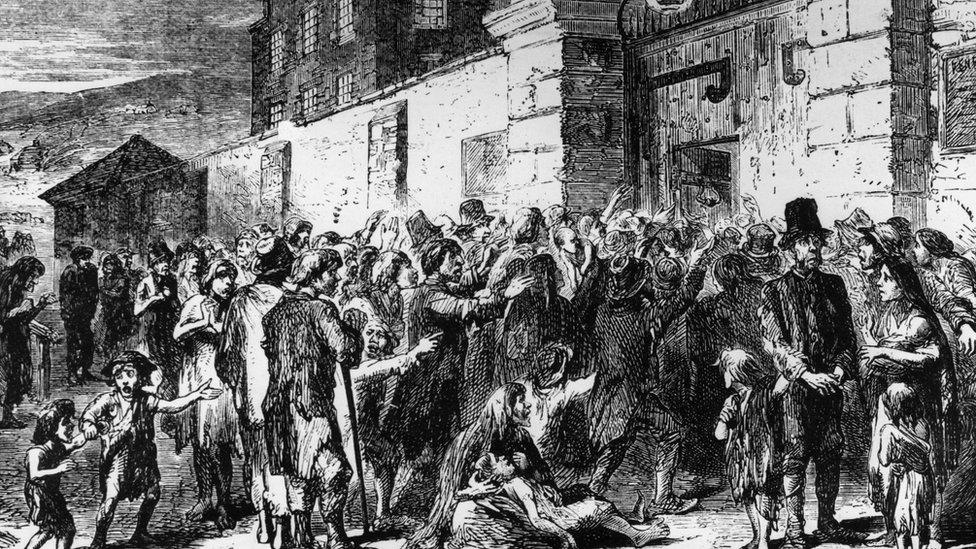

England's long and often painful relationship with Ireland went into overdrive in the Victorian era, thanks to the demand for labour, faster steamship travel and, tragically, the Irish famine of 1845-52.

Being legally part of Britain, the Irish needed no special permission to travel - but some incomers felt they may as well have come from the moon.

Robert Winder, author of Bloody Foreigners, says: "I don't think anyone has been the subject of such bitter feelings as the Irish in the 19th Century.

"This is partly because they were Papists, the religious dimension, but also they were really poor.

"They were felt to be squalid, verminous, unreliable criminals."

Many Irish immigrants were seen as bringing disease and squalor

An 1836 Royal Commission, actually aimed at helping the Irish poor, nonetheless said they brought "filth, neglect, confusion, discomfort and insalubrity".

Between 1841 and 1851, about 1.5 million Irish people - nearly 20% of the population - moved through England.

The Times in 1847 reported an "Invasion", saying: "Ireland is pouring into the cities, and even the villages of this land, a disgusting mass of famine, nakedness and dirt and fever."

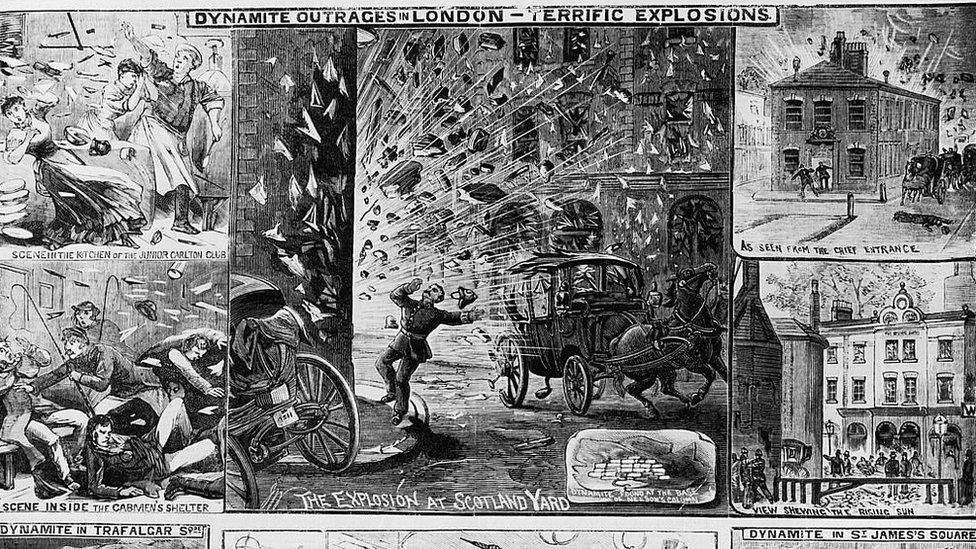

Fenian bombings and shootings brought the threat of violence into the Irish question

In 1861, the census showed 602,000 Irish-born in England and Wales - about 3% of the population. Nearly 20% of Liverpool's population was Irish.

Fears were stoked by both religious and political violence. There were anti-Catholic riots during the 1850s and 1860s.

The Irish radical - the Fenian - became a Victorian bogeyman.

The South London Press in March 1867 said: "As to the foreign plotters who have imported themselves into these realms for treasonable purposes, there ought to be no mercy or hesitancy; a short shift and a strong cord ought to be the fate of every such a man as shall be proved to be of this class."

The 1905 Aliens Act defined "undesirable" migrants and set up background checks but it was deemed unworkable

But again violence abroad brought new challenges.

Bloody pogroms in Russia and Prussia forced about 200,000 Jews to Britain - bringing radical politics and cheap labour.

Sir John Colomb, MP for Bow and Bromley, said in 1888: "England was being made a human ash pit for the refuse population of the world."

In January of the same year, The Morning Post said: "No one can doubt that there is a very serious side to this wholesale immigration of poor Russian Jews... it may become a source of positive danger and demoralisation to a large section of our working population."

The established - and often successful - Jewish community tried hard to help but this highlighted the immigrant Catch 22. If they were successful, they were greedy fat-cats; if poor, they were idle leeches.

The outbreak of war 1914 saw national security used to slam the doors firmly shut.

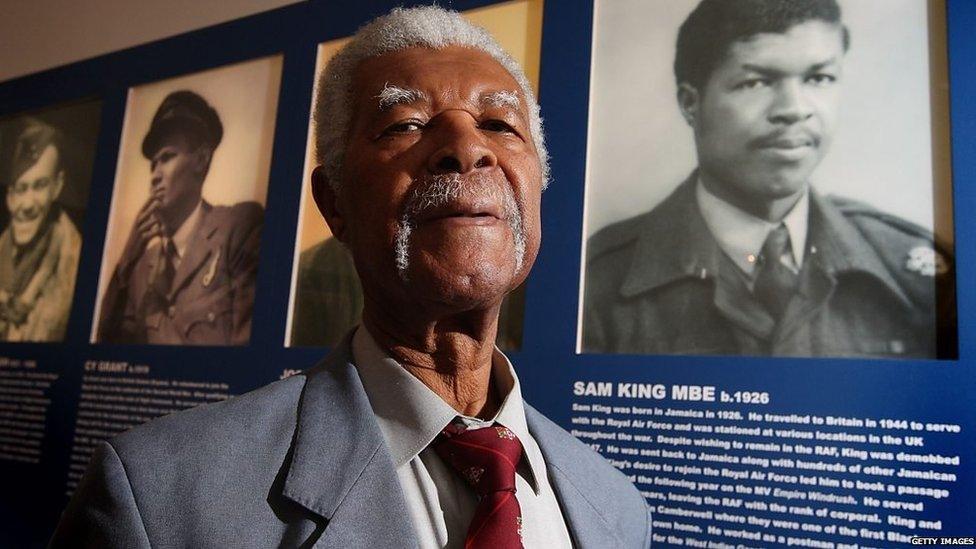

The Windrush generation began a new era of immigration to Britain

Following World War Two it was Britain's fading Empire that laid the foundations for a new era of immigration.

Needing new workers after 1945, Britain took in or allowed to stay tens of thousands of people from continental Europe, with little controversy.

But a call was also made to the colonies and when steamer Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury in June 1948, with about 500 Caribbean passengers aboard, it made front-page news.

The Evening Standard greeted the "sons of Empire" with a large "Welcome Home!" headline.

The modern phase of mass migration was under way - but the fears and arguments it provoked had been well practised through the centuries.

- Published2 May 2018

- Published2 May 2018

- Published12 April 2018

- Published18 January 2018

- Published23 September 2016

- Published25 February 2013

- Published20 July 2012