Aethelflaed: The warrior queen who broke the glass ceiling

- Published

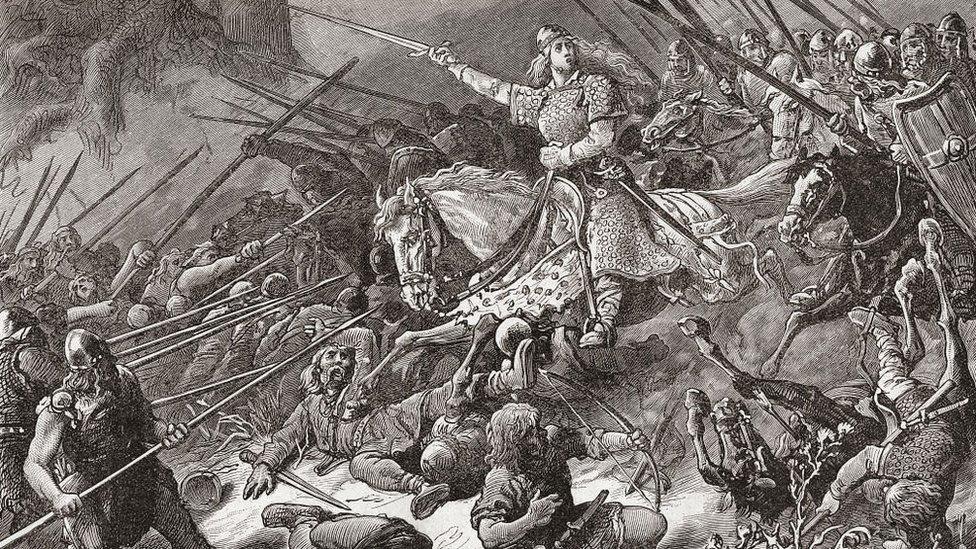

Aethelflaed not only ruled skilfully but might even have led her armies into battle

How does a ruler defeat bloodthirsty invaders, secure a kingdom and lay the foundations for England - and then almost get written out of history? Be a woman, that's how. Exactly 1,100 years after her death Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, is emerging from the shadows.

Born into a tooth-and-nail war for survival against Viking invaders, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred the Great, grew up in a realm teetering on the brink of disaster.

In 878 the royal family was forced to flee to the swamps of Somerset - just months before Alfred turned the tables and won a stunning victory over the Vikings at the Battle of Edington.

Married at 16 to Aethelred, Lord of Mercia, Aethelflaed's new lands were the front line as an uneasy and fitful peace came to a fiery end with Alfred's death in 899.

The British Isles had been split by waves of invasion into rival kingdoms

Dr Clare Downham, from the University of Liverpool, said: "She must have had quite a force of personality to overcome the assumptions of her time.

"It is a mark of her success in male-dominated times she was accepted as a ruler and achieved incredible - even unique - things."

You may also like:

Mercia had once covered the Midlands, but was split, north to south, by Viking conquests.

Viking rule was centred on three areas; York, East Anglia and in the Midlands, on the "five boroughs" of Leicester, Derby, Nottingham, Lincoln and Stamford.

Who was the warrior queen Aethelflaed?

Aethelflaed's marriage strengthened an alliance between Mercia and Alfred's Wessex in the south west and south east, the last Saxon kingdoms resisting a complete Viking victory.

Her background meant she had some preparation for the huge challenges ahead.

Dr Downham says: "She was given the same education as her brothers, and the crises of her childhood must have given her a schooling in the realities of politics and war.

"But Wessex had a tradition the king's wife could not be called a queen.

"Mercia had a stronger tradition of women taking part in the life of court and administration. Here Aethelflaed's talents could shine."

Aethelflaed was celebrated in medieval times but almost written out of some Saxon records

As her older husband's health declined, Aethelflaed's reputation seems to have grown.

Building projects, treaties and even - unusually for a woman - military campaigns, were conducted in her name.

An Irish chronicler, observing her skilful handling of troublesome Vikings in Chester, called her "Queen of the Saxons".

The greatest family?

Alfred the Great was ranked at number 14 in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons

Alfred the Great was the youngest of four brothers, all of whom became King of Wessex

Aethelflaed was his oldest child probably born in 870, with Edward the oldest son and heir

Aethelflaed had one child, a daughter called Aelfwynn

Edward was married three times, with Aethelstan his oldest child

Alfred stopped the Vikings but it was Aethelflaed and Edward who retook much of England

Aethelstan conquered the last Viking kingdom, York, and is regarded as the first true King of England

Dr Downham says: "She does not strike me as a belligerent leader; one of her skills seems to have been as a negotiator.

"Women in Anglo-Saxon England were sometimes called 'peaceweavers', because in a masculine, competitive culture it was perhaps easier for women to negotiate a solution.

"She negotiates with Vikings and they don't strike me as the easiest people to sit round a table with."

A castle now stands on the site in Tamworth that played a central part in Aethelflaed's life, and the town is holding several events to mark its association with her

With Aethelflaed working - perhaps uneasily - with her brother Edward, who had succeeded Alfred, the Saxons went on the offensive, conducting raids deep into Viking-held lands.

The inevitable reprisals saw a vengeful army of York Vikings fall on Mercia.

As the invaders burnt and looted, Aethelflaed and Edward gathered their forces and struck at the chosen moment.

At the Battle of Wednesfield, probably near Tettenhall in the West Midlands, the northern Vikings were annihilated, shifting the balance of power.

When Aethelred died, probably in 911, the nobles accepted his wife should become sole ruler, the Lady of the Mercians.

No contemporary portraits exist but Aethelflaed has been reimagined for various generations

The pace of activity seems to have quickened. Over the next few years numerous towns like Bridgnorth, Tamworth and Stafford were fortified to secure roads and rivers.

Dr Downham says one striking fact is something Aethelflaed did not do.

"She did not remarry. This is for two likely reasons - a new husband would become her lord with control over her territories.

"But also the religious literature of the time said a celibate woman was more manly and therefore she would be taken more seriously.

"It also seems her only child, a daughter, did not marry at all."

Now a sleepy village, Shearsby in Leicestershire may have been where a war began

Feeling secure in the west, Aethelflaed made her boldest move, seizing the town of Scergeat - likely Shearsby in Leicestershire.

This was too close for comfort for the Vikings of nearby Leicester.

In 913 an army was sent to bring the Mercians to heel. It was repelled.

The following years saw the Mercian army defeating both Welsh and Viking raiders.

The Irish chronicle says "her fame spread in all directions" and "through her own cleverness, made peace with the people of Alba and the Britons [Scotland and Wales]".

Then in 917 Aethelflaed struck east at the five boroughs. The Viking stronghold of Derby fell to the Mercians - the army perhaps led in person by Aethelflaed.

The next year the previously aggressive Vikings of Leicester - now isolated due to Saxon gains in the south and west - surrendered to the Lady of the Mercians without a fight.

Even York, the nerve centre of northern Viking rule, promised to obey her command.

So why is Aethelflaed's name not blazoned across British history?

There has been a rise in interest in female warriors, including portrayals of Aethelflaed herself played by Millie Brady in BBC drama The Last Kingdom

Alison Hudson, from the British Library, says: "It's about who wrote the history. The main source for the period, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, comes in different versions.

"The most commonly used version was written in Wessex, under the reign of Edward, and it almost writes her out of existence.

"While Aethelflaed is subduing the Welsh and Viking raids, taking Derby and Leicester, the Wessex chronicle concentrates entirely on Edward."

Most of her achievements are contained within a different version of the chronicle.

Ms Hudson says: "This contains something called the Mercian Register, which gives far more credit to Aethelflaed.

"Tellingly, records from Ireland and Wales, beyond the reach of an Edward who has designs on Mercia, really big her up."

St Oswald's in Gloucester was one of Aethelflaed's major building projects and where she was laid to rest

But at the height of her success, tragedy struck. Aethelflaed fell ill. She was taken to Tamworth, where she died on 12 June 918 probably aged 47 or 48.

She was buried in a church she had ordered to be built, St Oswald's, in Gloucester.

More about Aethelflaed: The warrior queen

In an unmatched moment, the succession passed, without opposition, from the mother to her daughter, Aelfwynn.

Dr Downham says: "She is unique in Anglo-Saxon England as a woman ruling in her own right and unique in British history in that she passed her power on to her daughter.

"This is probably testament to the respect earned by a woman who was key to the founding of England."

But it was not to last.

Wary of Mercian power, Edward marched north and deposed his niece, Aelfwynn. What happened to her next is unknown, although it has been suggested she might have entered holy orders.

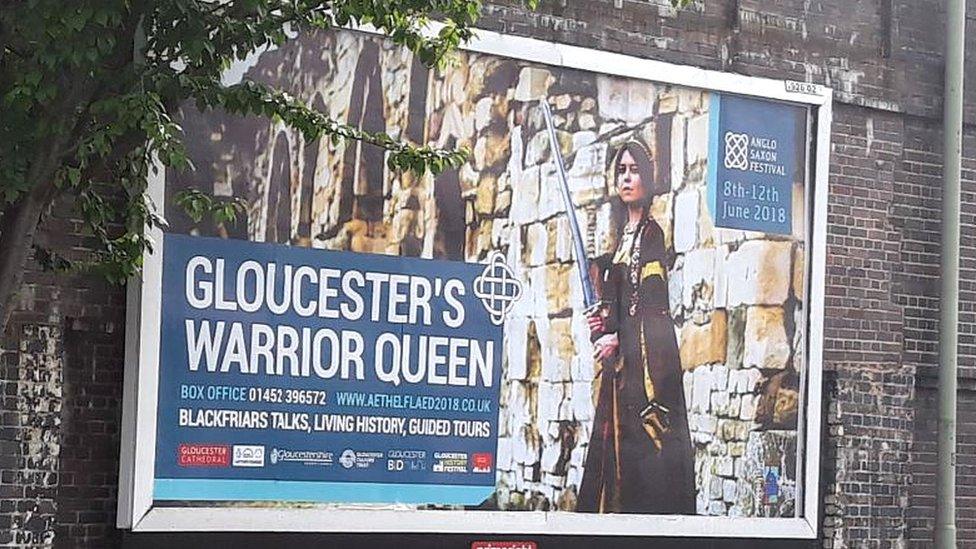

Gloucester is celebrating its close links with the story of Aethelflaed with a series of events

Despite the fate of her daughter, Aethelflaed's legacy was still a significant one.

Edward's son Aethelstan - Aethelflaed's nephew - had been brought up in the Mercian court and, after Edward died fighting Mercian rebels, Aethelstan was accepted as their king.

He also succeeded to the throne of Wessex and, using the lessons learned at Aethelflaed's side, became the first true king of a united England.

Dr Downham says: "She never entirely went away, being praised in some medieval chronicles - even if that praise was that she was 'as good as a man'.

"And she enjoyed a revival in the reign of Victoria, when female role models, like Boudica, were popular.

"And today, perhaps women are again looking for strong female role models, and this anniversary more than previous ones may generate greater interest in the role of women in England's past."

- Published10 June 2018

- Published5 August 2016