Poverty link to early death 'scandalous'

- Published

Glasgow, pictured, has the 5th highest avoidable death rate in Scotland

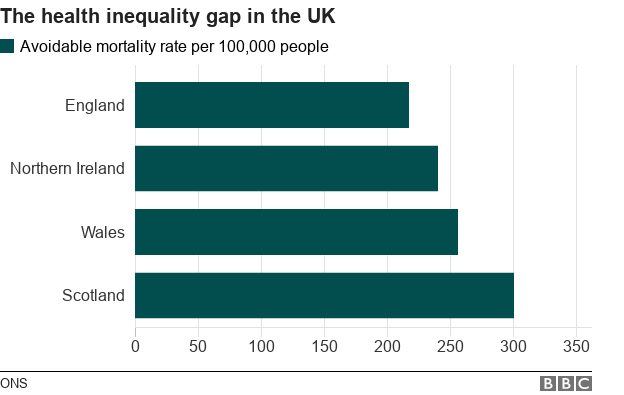

People living in the poorest parts of the UK are more likely to die prematurely, BBC analysis shows.

The mortality rate from avoidable causes is more than three times higher in some of the most deprived parts of the country than the most affluent.

Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham said such health inequalities were "scandalous in 2018".

The government said it was taking action to help people live longer and healthier lives.

The BBC's Shared Data Unit analysed data from the Office for National Statistics with deprivation data for local authority areas in England and Wales, as well as comparable data for Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Our analysis found a strong correlation between deprivation and the number of people dying prematurely.

Avoidable death rates range from 138 deaths per 100,000 in affluent areas such as Chiltern in Buckinghamshire, to 517 in the poorest parts of Belfast.

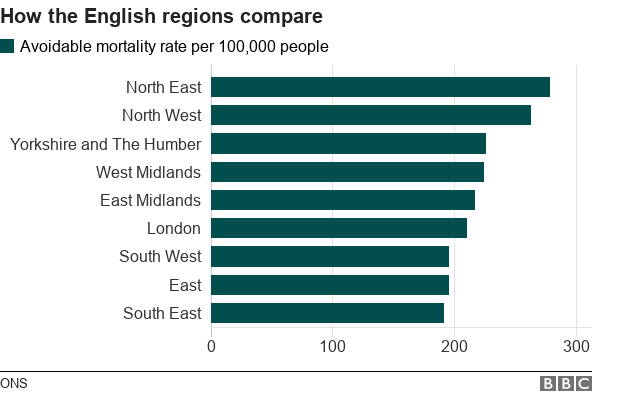

Mr Burnham said the findings were a "stark reminder of the huge health inequalities that exist between the north and south of England".

He added: "It is scandalous that in 2018 people's life chances are still determined by the postcode of the bed they were born in."

In England - Chiltern, South Oxfordshire, South Cambridgeshire and Hart in Hampshire had the lowest avoidable death rates.

Places with the highest rates include Manchester, Blackpool, Middlesbrough, Hull and Liverpool.

"My doctor told me I was eating myself to an early grave"

Father-of-two Mark Oldfield turned his life around after his GP told him he was heading for an early grave

A stark warning that he could be dead by next Christmas prompted father-of-two Mark Oldfield to take determined steps to avoid a premature death.

Diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure - the factory supervisor from Dudley topped 24 stone at his heaviest in January 2016.

The 50-year-old says he had always been overweight but when his doctor told him he was heading for an early grave it was the warning he needed to ditch his unhealthy ways and diet of takeaways, pizza, crisps, fizzy drinks and cider.

He said: "My diet was typical of my lifestyle - no time for anything, takeaways and jar sauces. I did no exercise and I once nearly got stuck in the turnstile at West Bromwich Albion because of my size.

"I was morbidly obese. My doctor told me I was eating myself to an early grave and in December 2015, shortly after I experienced an episode of breathlessness and dizzy spells, his words 'enjoy this Christmas - it may be your last' really hit home."

The warning came with a referral to a slimming group in Netherton on a 12-week programme - which helped him to lose more than nine stone through healthy eating and an exercise plan.

He said: "I think people become ignorant to weight problems, buy baggier clothes to hide it and carry on. It sometimes needs a short, sharp shock to make you wake up and do something about it. Thank God I listened. I've been given a second chance - I'm not throwing it away.

"I feel great and alive for the first time in years."

Figures released on Wednesday, external showed Hull also had the highest overall mortality rate in England and Wales, with 1,346 deaths per 100,000 people in 2017. The city replaced Blackpool as having the highest mortality rate.

Jon Date, head of external affairs at the independent think tank the International Longevity Centre - UK, said: "The reasons behind these disparities are complex, but it is utterly unacceptable to witness a growing health divide in 21st Century Britain."

What is an avoidable death?

Deaths in people under 75 from heart disease, some cancers, respiratory conditions and type 2 diabetes are among those classed as avoidable.

The list dates back to the 1970s when it was drawn up to help develop effective healthcare.

What is being done?

The Department of Health and Social Care (DoH) said more than £16bn was being invested in local government services to tackle public health issues in addition to free NHS health checks and screening programmes.

It also offers a free flu vaccination programme, a national diabetes prevention programme, a childhood obesity plan and a tobacco control plan.

A DoH spokesman said cancer survival was at a record high, with smoking rates at an all-time low. She added: "Generally, people are living longer."

Wales

The highest rate was found in Merthyr Tydfil (319 per 100,000 people), the second most deprived area in Wales; while Monmouthshire - the least deprived - had the lowest rate at 198.

Dr Chrissie Pickin, from Public Health Wales, said improvements had been made with heart disease through a reduction in smoking, but cases of liver disease, mental illness and substance misuse had risen.

Labour's Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney MP Gerald Jones said the Welsh Government had pumped significant funds into public health over the last 20 years but given the history of heavy industry in areas like Merthyr Tydfil there was a higher incidence of long-term illness.

Scotland

The avoidable death rate varied from 373 deaths per 100,000 in North Ayrshire, where there are high levels of deprivation, to 185 per 100,000 in Shetland.

A spokesman for North Ayrshire Health and Social Care Partnership said avoidable mortality was "inextricably linked to higher levels of deprivation".

He said the most important course of action was to work with the Scottish Government to bring investment and jobs to the area.

Dr Andrew Fraser, from NHS Health Scotland, said: "It's not right that there are such dramatic differences in life expectancy due to circumstances largely beyond a person's control."

Northern Ireland

The Department of Health in Northern Ireland said reducing inequalities was a "huge challenge".

A spokesman for the Public Health Agency in Belfast said: "It is well established that the poorest people live the shortest lives with the worst health."

To help change this trend the agency has invested in organisations which deliver health and wellbeing programmes - particularly in communities with high deprivation.

Among them are The Heart Project, which offers rehabilitation to people in Belfast who have suffered heart attacks or strokes, and a network of healthy living centres based in areas of high health inequalities.

'I couldn't even put my own shoes on'

Belfast father-of-six Gerard O'Neill says he doesn't know where he would be if he had not been referred to one of the city's healthy living centres.

Mr O'Neill has lost 12 stone in two years after receiving help from the Maureen Sheehan Centre in West Belfast.

Gerard O'Neill weighed 27 stone before he was referred to one of Belfast's healthy living centres

The 55-year-old former fisheries officer was initially referred on a 12-week Healthwise plan by his GP after his weight ballooned while caring for his elderly mother as she battled dementia.

He said: "I hadn't got any time for myself and I was eating a lot of junk."

However, following his mother's death he decided he had "to do something" about his health and went to see his GP who referred him to the Maureen Sheehan Centre which has a small gym.

He said: "Without this service I honestly don't know where I would be."

Mr O'Neill, who also started attending slimming classes, weighed 27 stone to begin with and said: "I couldn't even put my own shoes on, my breathing was very bad and I couldn't walk much distance."

Through healthy eating and regular exercise, however, his weight dropped to about 15 stone - and he has even completed two 5k charity walks to raise money and awareness of Alzheimer's.

Not content to stop there - he has also rekindled a passion for handball and now coaches a youth team. He has also completed a training course to rehabilitate cancer and heart attack survivors.

"It's great to return something back," he said.

More about this story

The Shared Data Unit makes data journalism available to news organisations across the media industry, as part of a partnership between the BBC and the News Media Association. This piece of content was produced by local newspaper journalists working alongside BBC staff.

For more information on methodology, click here, external. For the full dataset, click here, external. Read more about the Local News Partnerships here.

- Published19 July 2018