Why doesn't prison work for women?

- Published

Women make up just under 5% of the prison population in England and Wales, yet they are more likely than men to reoffend. Why doesn't prison work for women and what is being done to improve outcomes for them?

"The last day, I was given a bin bag of my stuff. The door closed behind me, and it was over.

"But no-one helps you on the outside, and anyone who hasn't been through it can't even begin to understand."

In 2011, Lisa* spent three months in prison for her involvement in a fraud. Despite receiving a relatively short custodial sentence, the impact was life-changing.

Away from her daughters, she questioned her abilities as a mother and her mental health began to deteriorate.

"I hadn't wanted to see my girls when I was inside because I didn't want to put them through that.

"When I got out, there were some days I couldn't face picking the girls up from school because I knew parents were talking about me. I had panic attacks just walking to the shops. I got paranoid.

"Once you've been inside, it's like your mind goes back when you least expect it.

"The walls are in your head, it's even worse than sitting in your cell."

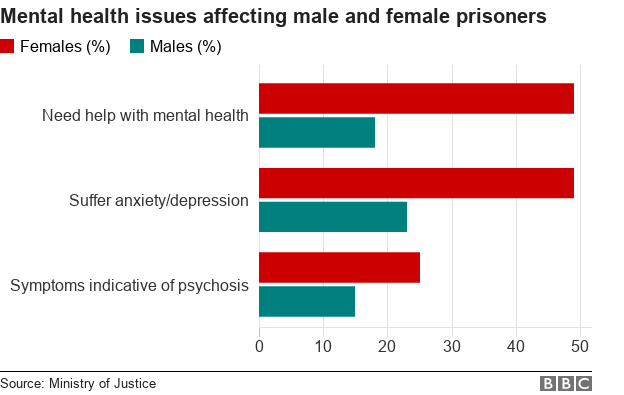

Female inmates are also more than twice as likely as men to report needing mental health help

According to the Women in Prison charity, 84% of women entering prison in 2017 committed a non-violent offence - often for crimes such as theft, handling stolen goods and non-payment of council tax.

As a consequence, they are likely to receive shorter sentences, which studies have shown link to higher rates of reoffending.

Lisa believes the fact she was in prison for a matter of months played a part in the lack of support she received.

"Even the officers said there was not much they could do to help me because I wasn't in for long enough," she said.

A Ministry of Justice report last year, external found short-term sentences served by both men and women were "consistently associated with higher rates of proven reoffending".

But analysis shows that women serving sentences of less than a year are more likely to reoffend than men with comparable sentences - although they are slightly less likely to reoffend overall.

Female inmates are also more than twice as likely as men to report needing mental health help.

Penal reform charity the Howard League says women account for one in five of all incidents of self-injury behind bars.

"Prison is a negative experience for everyone, but it is particularly distressing for women," says its chief executive, Frances Crook.

"They typically have more complex needs than men. They are more likely to be victims of abuse, and more likely to have been sentenced for offending related to their exploitation by a partner.

"And as women are much more likely than men to be primary carers of children, they are disproportionately affected by a short prison sentence.

"Even a few weeks in custody can be enough to cause a woman to lose her job, her home and her children."

Justice Secretary David Gauke announced plans to invest in community provision for women

Justice Secretary David Gauke said in June that female offenders are often amongst the most vulnerable of all.

"Many experience chaotic lifestyles involving substance misuse, mental health problems, homelessness, and offending behaviour... often the product of a life of abuse and trauma," he wrote in the Female Offender Strategy., external

"Evidence clearly shows that putting women into prison can do more harm than good for society, failing to cut the cycle of reoffending and often exacerbating already difficult family circumstances."

The government has said it is shifting towards community services to keep women away from prison, external and pledged to spend £5m over two years.

It has scrapped plans for five community prisons and instead will trial five residential centres helping women with drug rehabilitation and finding work.

"Women's centres can achieve what prisons cannot - working with other organisations in the community to ensure that women are given the support they need and guided away from crime," said Ms Crook.

"Prison does not work."

'Wall of silence'

About 60% of female inmates are a victim of domestic violence, external.

Yasmin Akhtar had been in a violent marriage and tried to take her own life before she spent two years at HMP Drake Hall for drug possession with intent to supply.

"When I was in prison, my family would tell everyone that I was working away because they didn't want to face the stigma.

"There was a lot of shame, being Asian and the first woman in my family to go to prison. There was a wall of silence."

The 43-year-old now works for Birmingham's probation service to help other female prisoners. It runs a reducing reoffending partnership with programmes specially for women.

Ex-prisoner Yasmin Akhtar is now a community support worker for Birmingham's probation service

"When I was in prison, I felt the freest I'd ever felt, because I'd been trapped in my marriage, in my life outside.

"There was counselling in prison which helped me. But some women didn't want it or respond to it well.

"It's a lot to accept and some are unable to do that straight away. That's what made me want to help other women when I got out."

Rehabilitating women through methods other than custody is something Marie-Claire O'Brien backs.

The former prisoner, who served 14 months for causing death by dangerous driving, said the key is investing in services to help women upon release.

"I didn't believe that I deserved a second chance," said the 37-year-old, who had therapy and rehab at HMP Send.

"I had to work through that with the support of the people around me. But for many women coming out of prison they don't have anything like that network at all.

"Prison can work for some women, I'm testimony to that, but for people who have committed low-level offences, it's not always fair to put them through the experience."

Marie-Claire O'Brien says women coming out of prison often don't have a network to rely on

Ms O'Brien has since set up the New Leaf Initiative, which works with former female inmates across the West Midlands to support them into employment.

She added: "I believe having well-run and well-funded prisons is important, but so is investing in the rehabilitation of women so their entire lives are not just completely defined by their time in custody."

The MoJ said its Female Offender Strategy will "help us deliver the best possible outcomes for women, placing greater emphasis on community provision and cutting the cost of female offending".

But while the move towards opening residential centres has been welcomed, charities have warned they must be properly funded.

Kate Paradine, chief executive of Women in Prison, said the level of funding currently available for female offenders is "pitiful".

"[Without an increase] the opportunity will be lost to transform the current shameful response to some of our most disadvantaged and vulnerable women and their families.

"We will be left with a broken system that fails victims and communities."

*Name has been changed

- Published24 August 2018

- Published27 June 2018

- Published27 June 2018

- Published27 May 2018

- Published24 May 2018

- Published27 April 2018