Should homeless people be expected to live in a box?

- Published

A computer-generated image of a new development set to be erected in Worcester

Single people in need of a home are the least likely to be prioritised by local authorities. But could one-person micro-homes be an answer - or is expecting people to live in a box, and be grateful about it, a step too far?

Nearly a quarter of a million single people have experienced homelessness in the past 12 months.

These include the most visible sector of homeless people, the rough sleepers; as well as those living in temporary accommodation, like shelters or hostels, provided by the voluntary homelessness sector. Then we have the "hidden homeless" who stay on the floor of friends and family, the "sofa surfers" and the squatters.

Perhaps communities of micro-homes such as one recently granted planning permission in Worcester - where each unit has a floor space of just 17.25 sq metres - could offer a solution.

An iKozie micro-home being winched into place. They are built off site before being lowered, complete, into their permanent position

According to the British Property Federation, micro-homes can be defined as "not conforming to current minimum space standards".

But the charity Homeless Link says "the main aspiration of people who are homeless is to have a home of their own".

So should we start to think inside the box?

Homeless people sleeping rough have a financial cost as well as a human one

Accommodating single people in small spaces is not new - shipping containers have been used to house homeless people for decades. But shipping containers are not purpose-built, are often cold, poorly ventilated and - crucially - are storage crates, not homes.

Benjamin Clayton, head of strategy at Homes England, external, the government's "housing accelerator" and formerly a fellow at Harvard University, says micro-homes are "clearly not the solution to the housing crisis, but they might be a handy resource in the meantime.

"Tiny houses could be particularly helpful in getting homeless people into safety. Housing charity Crisis estimates that the cost of a single homeless person sleeping rough in the UK is £20,128 per year, which is depressing money down the drain."

It makes financial sense to help homeless people, or, ideally, prevent their plight in the first place.

In an illustrative report At what cost?, external commissioned by Crisis, that annual price tag of £20,128 includes interaction with the criminal justice system (about £7,000), visits to A&E and stays in hospital (about £8,000), and support from homelessness agencies.

And that's before the human cost. Lacking a settled home can cause or increase social isolation, create barriers to education, training and paid work and undermine mental and physical health.

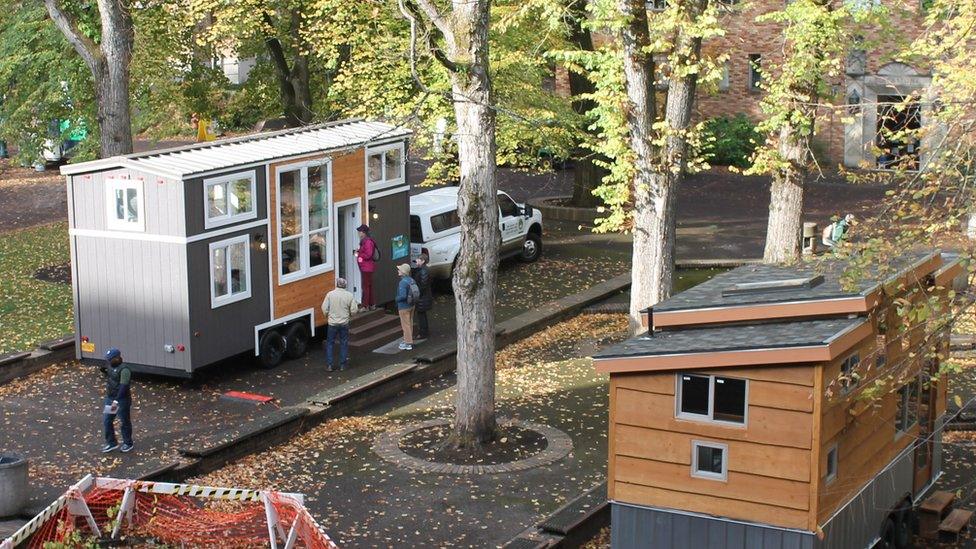

Tiny houses on show in Portland, Oregon

Mr Clayton suggests Britain should experiment along the lines of some communities in the US, where charitable groups have supplied micro-homes to help homeless people.

"Around 8,000 people slept rough on the streets of London in 2016-17, a number which has doubled since 2010," Mr Clayton says.

"Surely units in homelessness hotspots in London, Manchester, Birmingham and elsewhere could provide a real, albeit temporary, alternative.

"Of course Britain needs more and better real houses. In the meantime, though, we should take tiny houses seriously, especially for those who have no house at all."

Not everybody is happy with the idea though.

A village of tiny houses for homeless people has been built in Seattle

One of the newest developments to receive planning permission is a set of 16 iKozie units, which will be erected in Worcester some time next year. The original plans for the site were more ambitious, but vigorous opposition from residents worried about infrastructure, parking and antisocial behaviour led to the proposal for 30 units being trimmed down to 16.

Objections lodged with the council ranged from, external allegations that the iKozie residents would not be in paid employment and therefore a drain on the public purse, to concerns about space for charging points for hypothetical electric cars in the future.

Of the 16 units, five will be in the control of the city council's housing department, and it would be up to the council to decide who on the housing list should be allocated a unit.

Single adults with no children or specific vulnerabilities tend to fall between the cracks when it comes to finding them somewhere to live. There will always be someone considered a higher priority.

But these homes for one, loosely based on the cabin of a luxury yacht, could fill a gap.

The inside of an iKozie is divided into zones for sitting, cooking and sleeping

Each £40,000 home will be 17.25 sq metres and have a fully-equipped bedroom, shower room, living area and kitchen. The floor space of the units is half that set out in government guidance, but the company behind iKozie argues that the design, and the fact the units are not meant to be long-term homes, means their size is not a problem.

"A lot of affordable homes don't come with a cooker or flooring, and lots of people aren't brilliant at interior design," says the director of iKozie, Kieran O'Donnell, who is also a trustee of the housing charity The Homeless Foundation.

"With the iKozie, everything is fitted in. There are distinct 'zones' for living, eating and sleeping, and there is no wasted space."

Mr O'Donnell says the units would not be used to house the "street homeless", but would be for those moving on from supported living or "trapped in an HMO [home of multiple occupation]". The iKozie would provide transition accommodation for someone before they moved into the open market.

"It's not meant to be a long-term fix. I see the timeframe for people living there to be about two years-ish - perhaps giving people time to save for a deposit or even a mortgage," he says.

"At the same time, they're building up a track record of paying rent and for utilities, which can be shown to housing associations or whoever when they move on to the next stage."

The sleeping zone of an iKozie

The businessman is open about the fact that this project is likely to prove a financial success for his company - and he's currently looking for more sites on which to put more iKozies.

"We also think these will be in high demand for students or maybe older people who are downsizing."

The five affordable units would be rented at the local housing allowance rate - about £99 a week - while the remaining ones would be available for rent at the market rate of about £125 a week.

People living there would be subject to a strict set of conditions, Mr O'Donnell says. The units would be for single occupancy only and iKozie would monitor the site.

This in turn could free up space in a hostel or supported living accommodation.

So in concrete terms of helping the homeless, the effect will be modest - but could pave the way for further projects.

The Big Issue Foundation says there has been a "massive increase" in tented accommodation

Stephen Robertson, CEO of the Big Issue Foundation, says spiralling private rent has led to "a rough sleeping crisis, a humanitarian crisis" and even small initiatives like the iKozie development are valuable because of the lessons of the experience.

"There has been a massive increase in tented accommodation - people simply have nowhere to go," he says.

"The iKozies are small but they look fairly well designed and nobody is forced to live in one. They're not in themselves the answer - social housing is.

"If you look at the scale of the problem, this is just a drop in the ocean. But it is self-sufficient living, not being abandoned in a shed. Taking action where the environment is hostile is important - especially the learning that comes from it.

"We can find out from the development whether the project is scalable and replicable. I see it as an innovation; not more than that, but it is an innovation.

"It will be an improvement on many people's current situation.

"It is an alternative for people who don't have an alternative."

- Published19 October 2018

- Published13 September 2017