Grenfell Tower: The fires that foretold the tragedy

- Published

Dozens of people were killed in the Grenfell Tower fire, and many more were left homeless

On 14 June 2017, televisions across the country showed a west London tower block burn. For some, this was history repeating itself - as if five similar fires had simply not been important enough to prevent the deaths of 72 people in Grenfell Tower.

Catherine Hickman was on the phone when she died. It wasn't a panicked call or an attempt to have some last words with a loved one.

As a BBC Two documentary recounts, she had been speaking to a 999 operator for 40 minutes, remaining calm and following the advice to "stay put" in her tower block flat.

As smoke surrounded her, she stayed put. As flames came through the floorboards, she stayed put. At 16:30, she told the operator: "It's orange, it's orange everywhere" before saying she was "getting really hot in here".

Believing to the last that she was in the safest place, she carried on talking to the operator - until she stopped.

"Hello Catherine.

"Hello Catherine. Can you make any noise so I know that you're listening to me?

"Catherine, can you make any noise?

"Can you bang your phone or anything?

"Catherine, are you there?

"I think that's the phone gone [CALL ENDS]"

Miss Hickman was not a resident of Grenfell Tower. The fire in which she and five others died happened in July 2009, at 12-storey Lakanal House in Camberwell, south London. But that same "stay put" advice was given to Grenfell residents eight years later. Many of those who did never made it out alive.

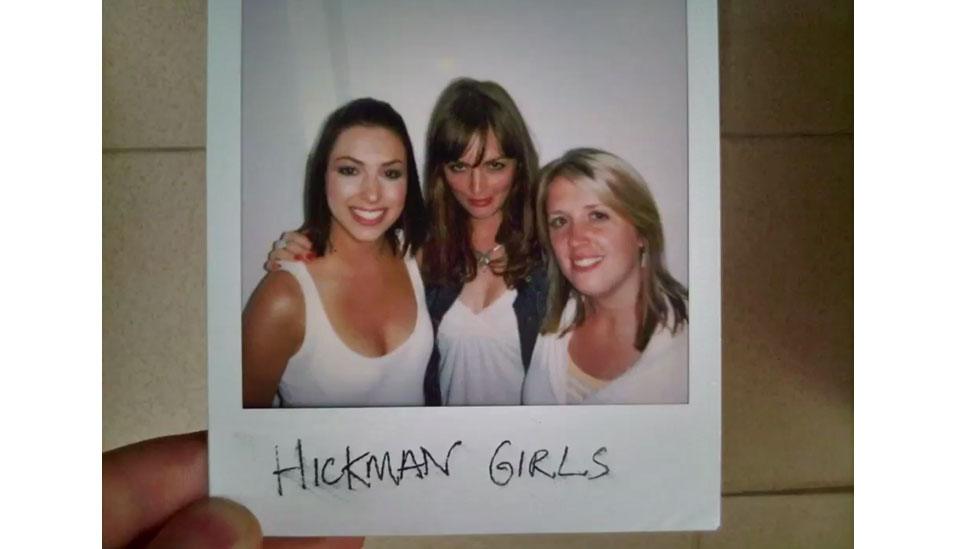

Catherine Hickman, a dressmaker, grew up on a farm with two sisters

Miss Hickman was one of six people who died in the Lakanal House fire after obeying instructions to stay in their flats

Catherine, a 31-year-old dressmaker, had grown up on a farm in Hampshire with her two sisters, Liz and Sophie. The three were close as children and remained so as adults. Her sisters could not understand why Catherine hadn't left the building.

After the fire, they visited Catherine's home and saw the bottom half of the rooms completely burned out. They could see her sewing machine, melted. Her dressmaking patterns were scorched, but somehow hadn't been entirely consumed by the blaze.

It wasn't until two weeks later Liz and Sophie learned that Catherine had not simply fallen asleep on the sofa, as they had hoped. She had been conscious and was waiting to be saved. For the two surviving sisters, it was a devastating revelation.

The "stay put" instruction is not inherently unsafe - if flats are properly hermetically sealed and fire-retardant. Guidelines state that an apartment in a tower block should withstand a blaze for an hour, giving enough time for inhabitants to be rescued.

The flats in the tower block were fire-resistant for just four minutes, the Lakanal House inquest established

But two years before the fire that killed Miss Hickman, the council had refurbished the outside of the building and installed false ceilings, "improvements" which helped the flames spread.

The flats were not fire-resistant for an hour - they were resistant for four minutes. As John Hendy QC, a barrister at the Lakanal House inquest, pointed out, that is "no resistance at all".

The refurbishment involved wrapping the building in a flammable cladding and there was no sprinkler system - both factors in the Grenfell Tower blaze eight years later.

When Sophie Hickman and Liz Watts saw the Grenfell disaster unfold, they were horrified their sister's death apparently hadn't changed anything.

"This is what was really upsetting about Grenfell," says Liz.

"You don't want her death to be in vain. You want answers. You know you want lessons to be learnt and that was the main thing."

Sophie says: "You just think 'this is just crazy - why has this happened again?'"

But the issues go back much further than 2009.

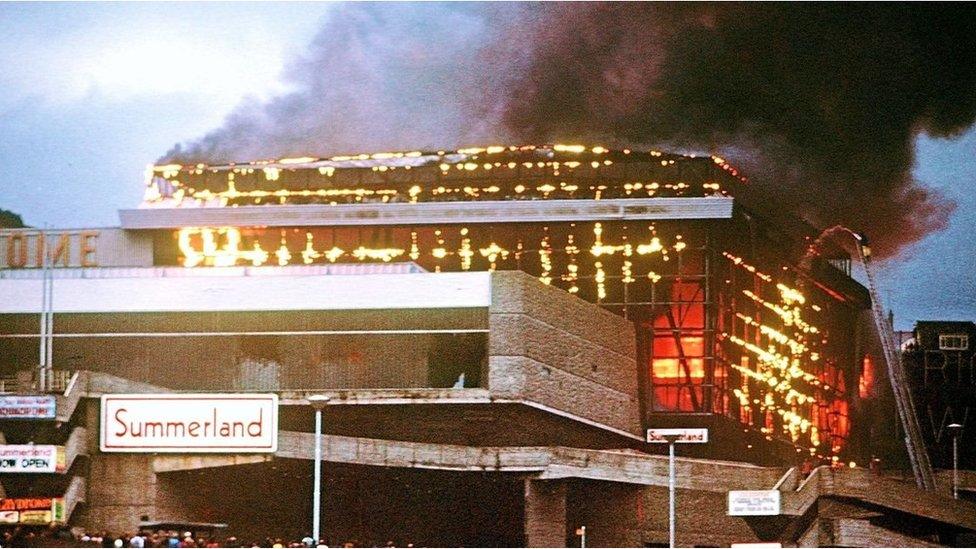

In August 1973, a fire at an indoor holiday complex on the Isle of Man claimed 50 lives, becoming the most deadly conflagration in the British Isles since the Blitz.

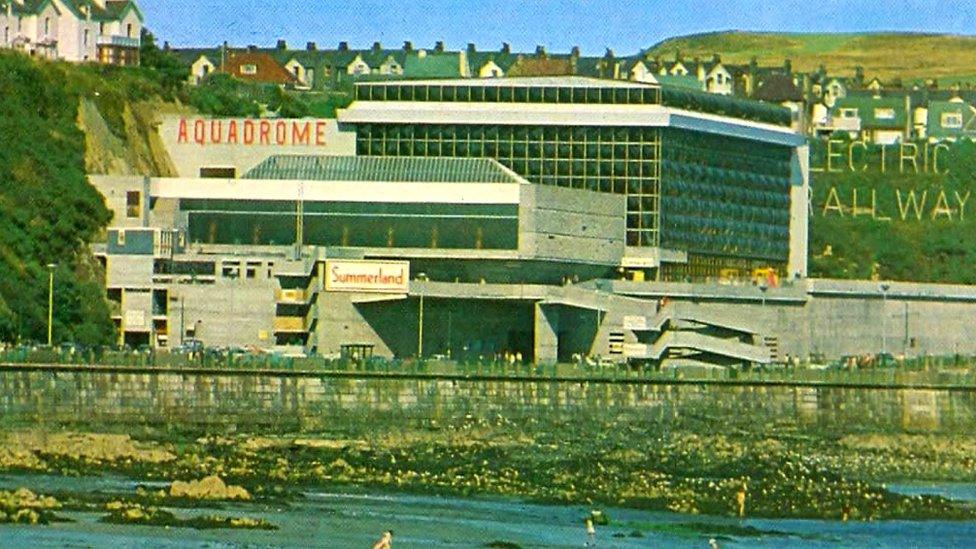

Summerland, a huge building capable of accommodating 5,000 holidaymakers, was coated with an acrylic substance called Oroglas, which meant visitors would not only be in a warm, climate-controlled building, but could even get a tan while remaining indoors.

This postcard advertising Summerland shows the building's Oroglas coating

There was only one entrance/exit for a building that could accommodate 5,000 people

Those behind Summerland hoped this would help dissuade holidaymakers from visiting the sunny Mediterranean in favour of a break in the Manx capital of Douglas.

But Oroglas was highly flammable, so much so that a police officer who attended the blaze took some shards home with him - the substance made an excellent firelighter.

To save money, sprinklers had not been fitted at Summerland.

The building's solarium (left) was clad in acrylic wrapping, which was to catch fire rapidly

People were told not to evacuate the burning building - 50 lives were lost

Sally Naden was a dancer at the resort at the time of the fire, which was caused accidentally by youths smoking cigarettes. She remembers the "stay put" advice was issued to holidaymakers as the building burned.

"There was an announcement and they said 'nobody panic, there's nothing to worry about'. So people didn't actually move. It was floor-to-ceiling flames and the heat was almost instantaneous.

"It was as if there was a waterfall of flames, that's the way it looked. I can remember somebody throwing their child over the balcony in the hope that someone would catch them."

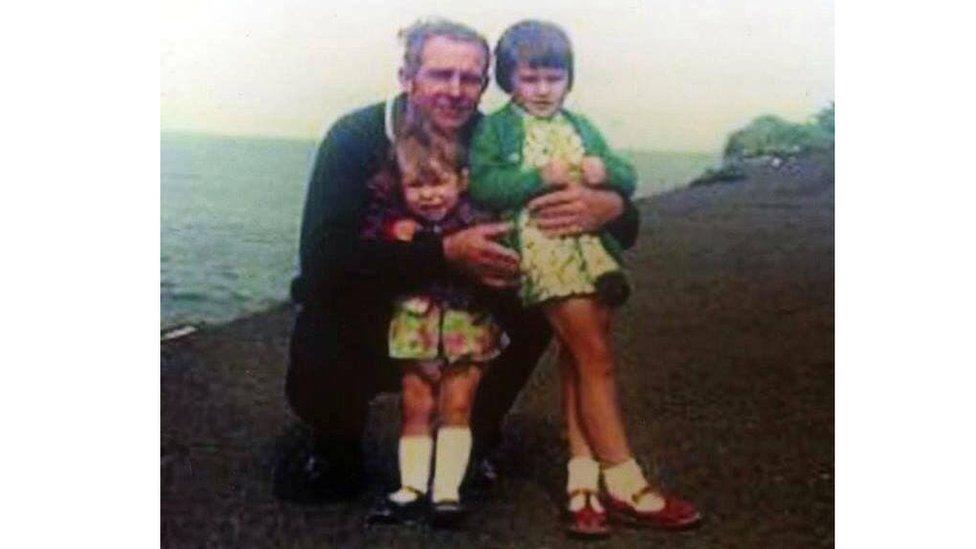

Ruth McQuillan-Wilson was a five-year-old on holiday with her family.

"Dad had spotted smoke coming out through a ventilation shaft and an announcement was made from the floor. It was smelting and burning lumps from the roof," she says.

"It fell on people's backs, a lot of people had back injuries. Dad's hair was on fire. And then we had to run through the flames.

"I was badly burnt at that point and I thought 'I'm going to die in front of all these people'.

"We had to escape over bodies, and I looked down at my hands and I couldn't understand what was wrong. The fingers were webbed, like a duck's feet. The skin was just all melted."

Ruth was on holiday on the island with her sister, mother and father. All survived the Summerland fire, but Ruth (on the right) was badly burned

Summerland was rebuilt on a smaller scale but eventually had to be demolished after torrential rain triggered two landslides behind the building

As parents and their children were dying, people were still told to stay where they were.

An inquiry after the fire recommended the installation of sprinklers in all large buildings and that external walls of large buildings should be fire resistant.

One of the firefighters who responded to Summerland, Godfrey Caine, says that his view ever since that day is "if you have a fire, get people out".

A disaster like this should never have happened again.

But nearly 18 years later, in April 1991, the newly-installed cladding on a tower block in Huyton, Merseyside, caught fire.

A fire was deliberately started at the base of the high rise

Knowsley Heights was well known as an eyesore, and in the mid-1980s the Conservative government launched Estate Action - a scheme to improve living conditions in tower blocks.

Cladding was installed as part of the revamp, but this caught fire when a pile of dumped furniture at the base of the tower was set alight by youths.

Caretaker Dave Soo was awoken by the sound of helicopters and ran to help firefighters evacuate the block. When he arrived, the cladding looked like it had disintegrated.

"It was hanging in strings," he says.

Tenth-floor resident Amanda Roberts - who had been pleased with the new cladding, thinking it looked "fantastic" - awoke to encounter thick black smoke and melting windows.

The stairwell of the tower block was effectively a chimney, allowing the flames to race up through the building.

Putting them out was problematic, as firefighter Les Skarrats explains, because the water being sprayed "was just hitting the external cladding and bouncing away".

"How do you deal with that? It was virtually impossible; we could not stop the escalation of that fire. We were lucky that we could get people out in time."

In a similar vein, the exterior panels on Grenfell Tower were installed as "rainscreen cladding". In other words, they were designed specifically to keep water away from the building. Afterwards, several firefighters described their hoses having no effect on the flames.

Nobody was killed in the Knowsley Heights fire, and an investigation afterwards found the cladding was legal.

Eight years later, in June 1999, a similar fire broke out in Irvine, western Scotland - this time with fatal results.

A dropped cigarette end caused the Garnock Court blaze

Garnock Court was one of five high-rise housing blocks in the town that had been clad for decorative reasons.

Before the makeover, there had been a number of fires in the blocks and all had been contained. But once the cladding was in place, it was a different story.

The blaze started with a dropped cigarette end in a flat on the fifth floor. The fire broke through a window and climbed the tower on the outside, spread by the plastic cladding.

William Linton - the man who had dropped his cigarette butt - was a wheelchair user and it was feared he had not been able to escape from his flat. Firefighters found his dog dead but there was no sign of Mr Linton himself.

It turned out that the fire had been so hot, he had been incinerated. His death was confirmed only by forensic analysis of the ash.

Again, recommendations were made. Combustible cladding was not to be used on high-rise flats.

A Select Committee report concluded "we do not believe that it should take a serious fire in which many people are killed before all reasonable steps are taken towards minimising the risks".

The report also said the danger of cladding systems was that fire might exit a building at one floor, spread up the building and re-enter on another floor.

It reads like a prediction of Grenfell.

Brian Donohoe, the Labour MP for Irvine at the time of the blaze, was part of that Select Committee and remains incredulous the recommendations were not acted on.

"Why didn't more take place in Westminster? Garnock Court was a lesson that unfortunately hadn't been learned by any of the governments that have been in position.

"The recommendations were received by the office of the Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott. But the response was poor and the response virtually kicked what was made as recommendations into the long grass."

Nearly six years later, in February 2005, two firefighters died in a blaze at a tower block in Stevenage, where residents had been told to "stay put".

Michael Miller and Jeff Wornham had gone into the flat in Harrow Court where the fire broke out. The man who lived there was rescued, but the woman, Natalie Close, died.

Some unattended tea lights on top of a television started the fire at Harrow Court

Mr Miller and Mr Wornham were also killed during the rescue attempt.

The "stay put" policy was based on the idea that people would be safer inside a self-contained flat than walking around a burning building trying to find a way out.

Michelle Camilleri had dialled 999 after spotting the fire from her 14th-floor flat. She was told to stay where she was and did so for more than an hour.

Eventually, with the fire still raging, she decided to leave. She recalls thinking: "If we are going to die, then we're going to die trying to escape."

"I grabbed my children and ran."

The Fire Brigades Union called for a review of the "stay put" policy and for sprinklers to be fitted in all tower blocks.

The three Hickman sisters were close as children and remained so as adults

Catherine Hickman obeyed instructions to stay in her flat

It wasn't done. Six years later came the Lakanal House fire, in which Miss Hickman and five others died.

Rasheed Nuhu and his family, who were in a neighbouring flat to Miss Hickman, were told to stay in their flat.

He considered the advice to be "preposterous".

"I thought, 'how can you tell people to stay in a burning building?'"

The Nuhus took shelter with their neighbours and another family, obeying instructions to shut themselves in the bathroom and hold damp towels over their faces. Then smoke started coming though a vent in the bathroom wall.

"At that point I thought 'no'," says Mr Nuhu. He and his family ran to the balcony, their friends remained in the bathroom.

The Nuhu family was trapped for 40 minutes before being led to safety by firefighters down a blackened and smoke-filled stairwell.

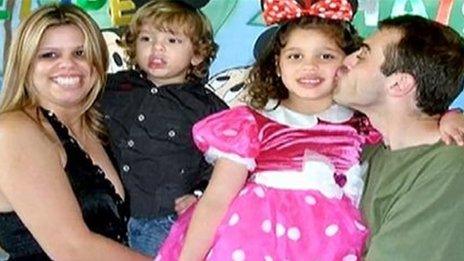

Rafael Cervi lost his whole family in the Lakanal fire - his wife Dayana Francisquini and their children Thais and Felipe all died while taking shelter in a bathroom

Helen Udoaka and her three-week-old daughter, Michelle, died in a bathroom with three others

When rescuers got to the bathroom, they found five bodies: Dayana Francisquini, 26, and her children, six-year-old Thais, and Felipe, three; Helen Udoaka, 34, and her three-week-old daughter Michelle.

Firefighters were metres away from Miss Hickman when a fireball ripped through her flat. They had to leave or they would have been killed themselves.

The coroner recommended that sprinklers should be retro-fitted to all tower blocks, that the "stay put" policy should be reviewed, and cladding should be fireproof. Communities Secretary Eric Pickles did not make the recommendations compulsory.

Harriet Harman was the Lakanal House residents' MP. She saw the building burn and to her it was obvious the "stay put" advice was not working.

She believes more should have been done to prevent future tragedies.

"Whatever all of us did, it wasn't enough," she says. "Because if you've got something that happened and six people died and then exactly the same happens again... and even more people died, then none of us did enough."

In 2016, a scruffy 23-storey tower block in North Kensington, west London, was wrapped in cladding to improve its appearance.

The following year, a faulty fridge-freezer set light to a fourth-floor flat.

The cladding was highly flammable.

There were no sprinklers.

Just before 01:00, the fire brigade received the first call from Grenfell Tower.

Residents were told to stay in their homes.

The Fires that Foretold Grenfell will be broadcast on BBC Two on Tuesday 30 October at 21:00 GMT and afterwards on the iPlayer.

- Published17 July 2018

- Published16 June 2017

- Published2 August 2013

- Published15 January 2013