Rail fare increases: Charts explain passengers' frustration

- Published

- comments

Commuters across the north of England have faced widespread cancellations throughout 2018

Rail fare rises have put about £100 a year on to the price of some annual season tickets, but passengers do not believe they are getting the service they are paying for.

Campaigners call it a "kick in the wallet" and analysis of official data by the BBC shows people are paying more for worsening delays, shortages of staff and, in some areas, an ageing fleet of carriages.

Trains clocked up 32 years of delays

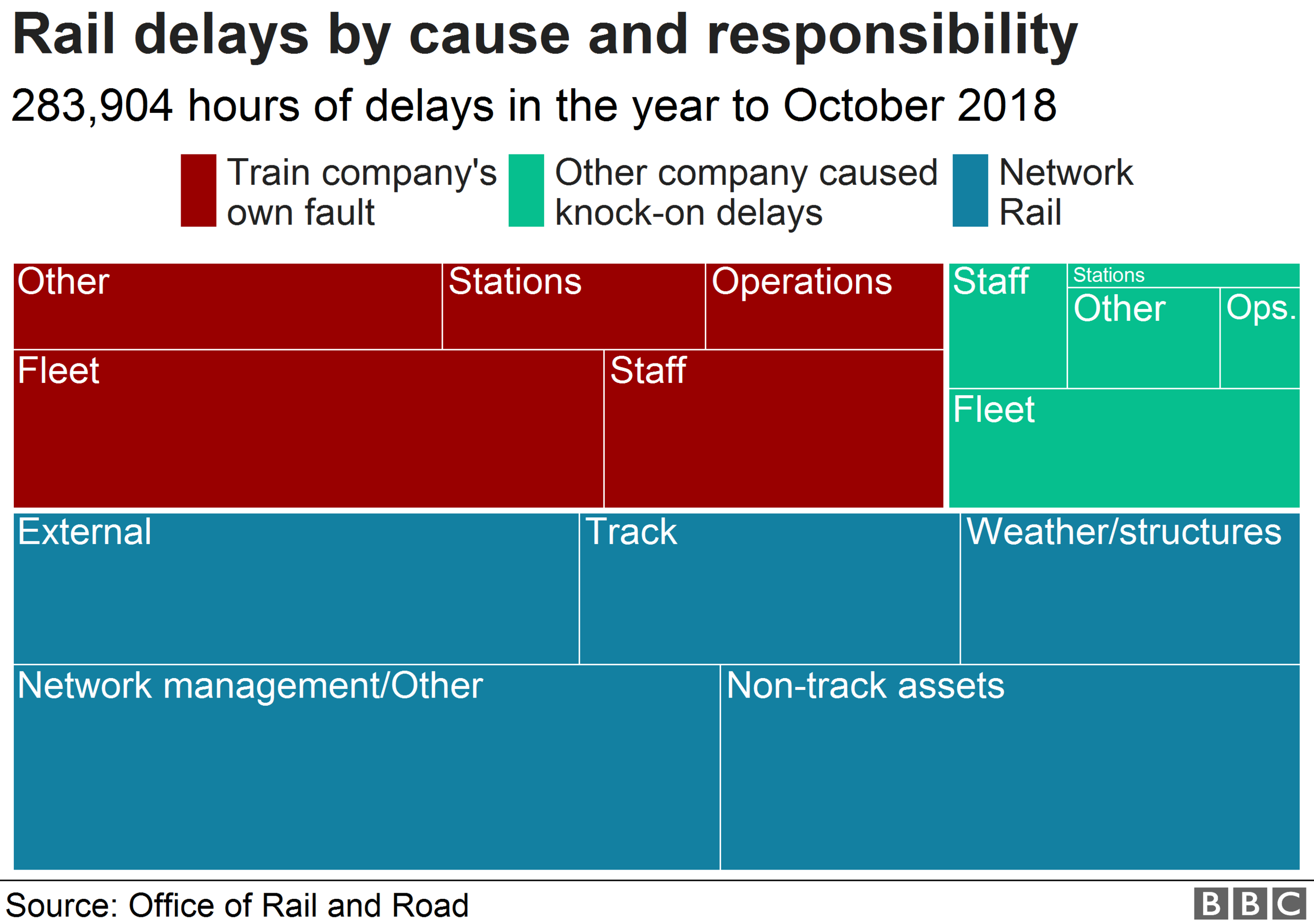

Total delays on the rail network in Britain added up to a combined 283,904 hours in the year to the middle of October 2018.

That works out as more than 1,690 weeks or about 32 years' worth of delays.

The Office of Rail and Road said total delay hours increased 22% since 2008-9, compared with a 10% increase in the number of trains running.

Network Rail, which owns and manages most of Great Britain's railway infrastructure, took the blame for the majority of the delays. Issues include damage to or failure of tracks, signalling and points and services being unable to cope with bad weather.

Not enough staff

The lack of key staff - such as drivers and guards - was behind more of the time lost to delays (25,335 hours) than the weather (18,907 hours) in the year up to mid-October 2018.

This included 5,542 hours of delays because train crew shortages caused knock-on problems for other operators.

Northern said it had to re-train 500 of its drivers, about a third, to navigate some of the new routes introduced following a timetable change in the summer, which contributed to delays.

Northern and South Western Railway staff have also gone on a series of strikes over planned changes to the role of train guards, however if operators ran amended timetables on strike days then the industrial action did not count towards the delay figures.

'Just not worth it'

Stewart Frank commutes between Malton and Leeds and has counted his delayed trips since May.

The lack of reliability has eroded goodwill among passengers.

Stewart Frank kept a count of his commute and found 100 trains in a row he travelled on to or from work in Leeds were late.

"It's disgraceful that fares have gone up," he said. "We can't rely on the service.

"I stand on the platform and the sign says it's two minutes delayed, then four minutes, then eight and then 10. If people knew it wasn't coming they could at least try to make other plans."

He and his wife Anca commute together and pay more than £300 a month each.

"It was already a ridiculous price but when you don't know if you're going to be at work on time or home more than an hour late it is just not worth it."

James Vasey, of the Bradford Rail Users Group, said he would previously have defended the fare increases but could not do so this year.

The secondary school associate assistant head teacher said: "I always used to say it's not the drivers' fault and it is right that staff are paid their salaries.

"This year I can't defend it because as passengers we are not getting what we're paying for. We haven't had the improvements or the new carriages we were promised.

"On strike days people have had to make sure not to travel after 17:30. At weekends they've had to avoid making plans that rely on the trains, yet they're being told to pay more for it."

Train operators are 'sorry'

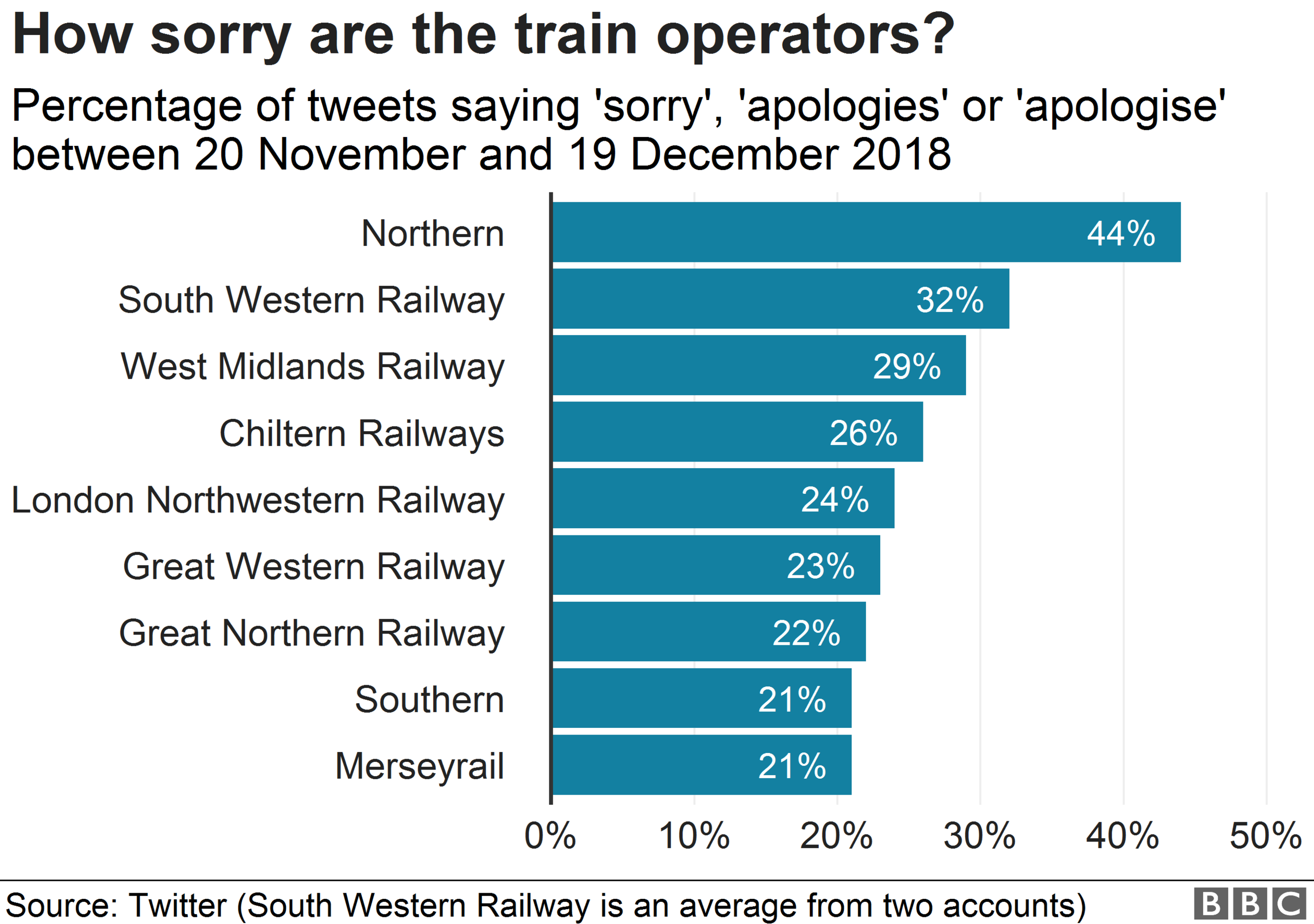

Train companies apologise to passengers frequently for delayed and cancelled services.

Northern, which recorded about a third of its trains arriving late in November and early December, apologised in more than four out of every 10 tweets sent between 20 November and 19 December 2018.

South Western Railway, which has seen strike action at weekends, said sorry in about 40% of tweets from one of its accounts, 30% from another.

Passengers demand compensation

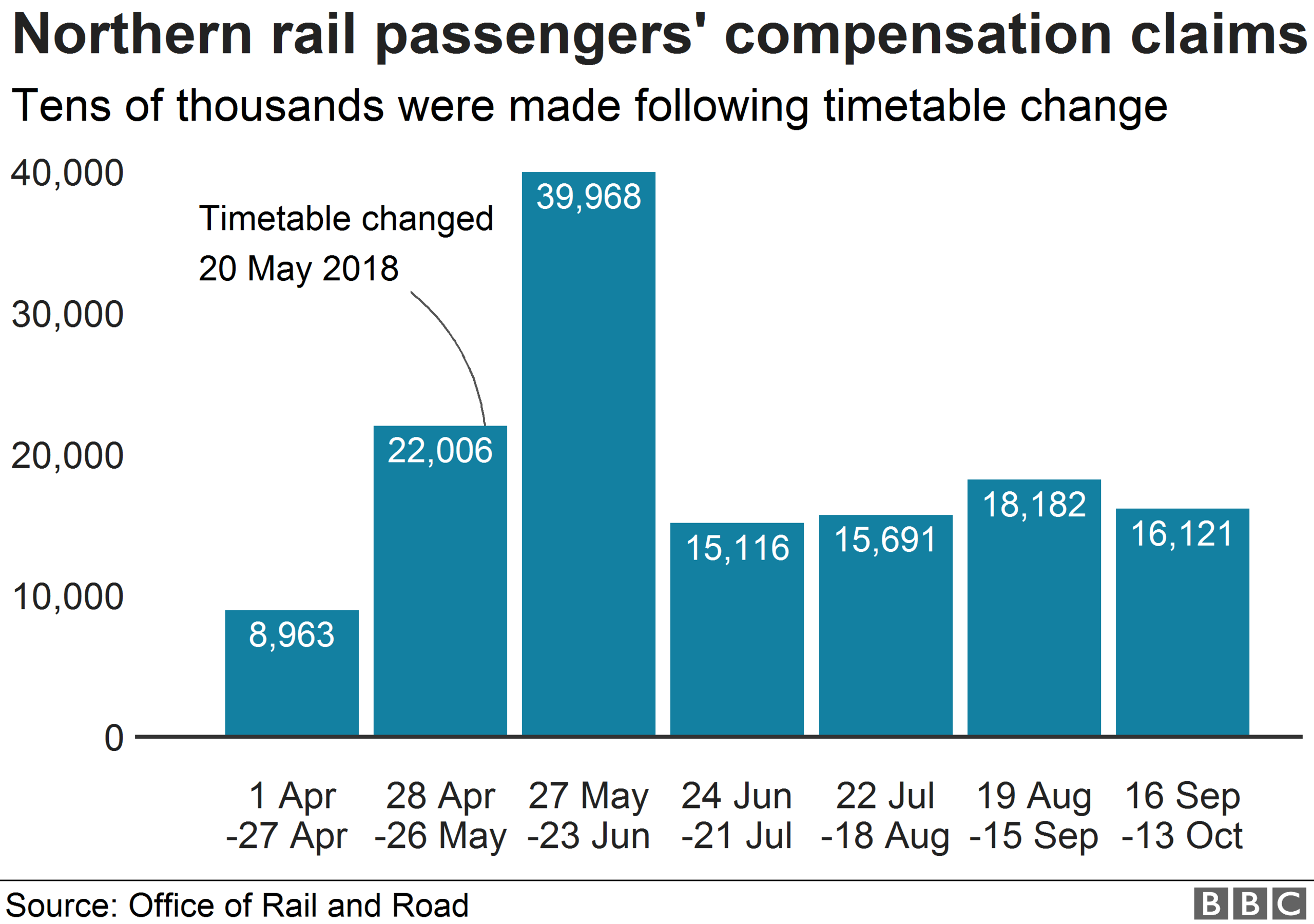

There was a surge in compensation claims from Northern rail passengers following the chaotic timetable change in May.

The Office of Rail and Road (ORR) said compensation claims had since "diminished but not returned to the levels seen before the timetable change".

It put this down to a lag in passengers submitting claims and people being more aware of compensation and more willing to make claims.

Rail companies refund passengers part of the cost of their journey, depending on the length of delay, external.

Older trains

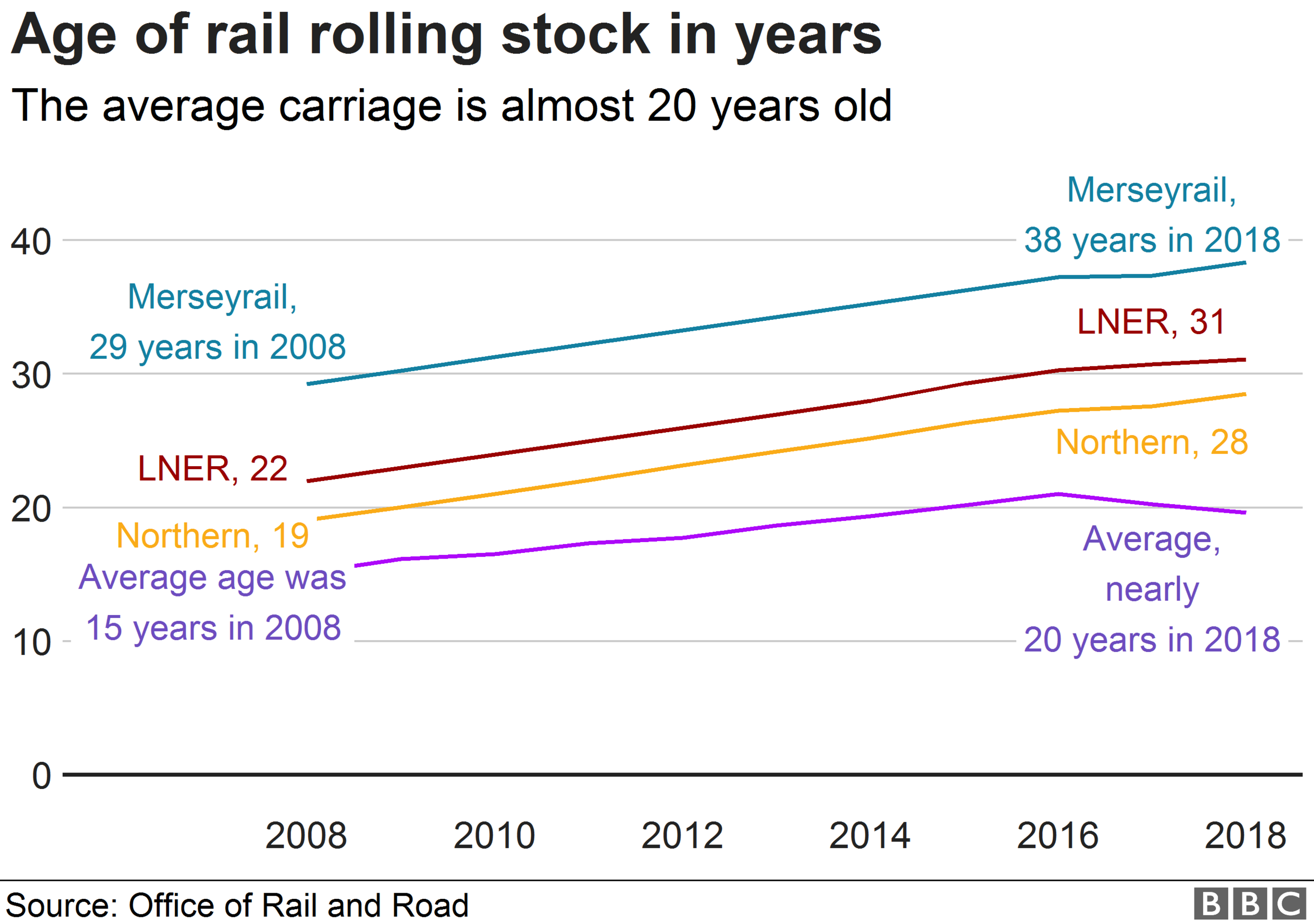

Operators insist that yearly increases in rail fares allow them to invest in the railways and in new carriages.

A decade ago the average age of rolling stock was 15.1 years. In 2018 it was 19.6 years. However, this is an improvement on 2016, when the average age reached a peak of 21.3 years.

Merseyrail's carriages are an average of 38 years old but the company is due to introduce a new fleet from 2020.

Some carriages and locomotives are purchased by the train operator and others by the government, which leases them to the operator.

"Delays to infrastructure and electrification also prevent the rollout of new trains even after they have been ordered," said Darren Shirley from the Campaign for Better Transport (CBT).

The Rail Delivery Group, which brings together train companies and Network Rail, stressed there were more than 7,000 new carriages on the way by 2021 while hundreds of trains would be "refurbished like new".

It said the Great North Rail Project provided a "multi-billion-pound programme of upgrades to better connect towns and cities across the north of England" while the Thameslink programme would mean a frequent service through the centre of London, "better connecting communities from Cambridge and Peterborough all the way to Brighton".

Annual price rises for regulated fares in England and Wales, which includes a lot of season tickets, were capped at an average of 3.1% for 2019.

In Scotland the average increase was 2.8%.

The CBT said it wanted to see a fare freeze, similar to the fuel duty freeze that has been in effect for nine years.

Mr Shirley said: "The whole fares system needs an overhaul, and it should be looked at through the review of the railways currently being undertaken."

Paul Plummer, chief executive of the Rail Delivery Group, said: "Nobody wants to pay more to travel, especially those who experienced significant disruption earlier this year.

"Money from fares is underpinning the improvements to the railway that passengers want and which ultimately help boost the wider economy. That means more seats, extra services and better connections right across the country."

- Published6 June 2018

- Published20 November 2018