War on fatbergs: Can this 21st Century peril be blitzed?

- Published

This "monster" fatberg was discovered in Whitechapel, east London, in 2017

Fatbergs always seem to pique people's interest: somewhat disgusting, yet strangely comical, they give us an insight into the alien world of the sewer networks that help keep our towns and cities running smoothly.

But they come at a cost. A very big cost.

Every year the UK spends about £100m clearing an estimated 300,000 fatbergs, the blockages created from the congealed fats and waste we pour down the sink and flush down the toilet.

Although London became associated with the fatberg phenomenon after it was revealed a "monster" longer than Tower Bridge was clogging up the city's sewers, this is very much a global issue: New York, Denver, Melbourne and Valencia have all found giant fatbergs blocking their waterways.

It's not just big cities that are affected either - sewer workers in the English seaside town of Sidmouth recently found a fatberg that was 210ft (64m) long.

And while water companies come up with all sorts of campaigns and strategies to try to stop us putting the wrong things down our sinks and toilets, we are still doing it.

So, is there another way to conquer the almighty fatberg?

The Museum of London had an exhibit about the fat blocking London's Victorian infrastructure

Deep in a water treatment plant in Ramstein, near Kaiserslautern in south-west Germany, one woman believes she's found the answer.

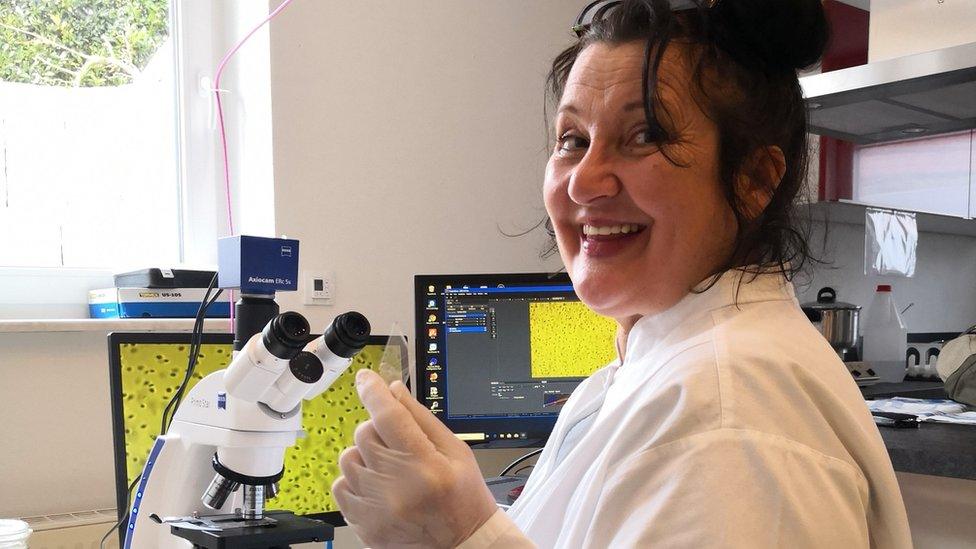

Dr Andrea Junker-Buchheit works for a start-up called Lipobak.

"We treat fatbergs with a special micro-organism solution. We grow bacteria which have been developed specifically to eat fat.

"They digest all the fat, all the grease, all the oil," she said.

Andrea Junker-Buchheit is trying to grow bacteria that can survive in the hostile environment of a sewer

Work in this area started under a US patent nearly 30 years ago, but has come back to the fore since it expired.

Ramstein has a problem with fatbergs, which, according to Dr Junker-Buchheit, is partly due to the fact the city has a US military base, which has brought with it a cuisine that is traditionally higher in fat.

"They are living here more in a US way of life than a German way of life, so we have a lot of burgers and restaurants like that."

The city's water treatment plant is therefore a good testing-ground for Lipobak's solution.

The bacteria that Dr Junker-Buchheit has been growing produce an enzyme called lipase, which eats fat, and needs more and more of it to survive and grow.

What causes fatbergs?

Lipobak is not the first company to try this.

A few different bacteria-based solutions have been tested in London with "mixed results".

Stephen Pattenden, from Thames Water, says the sewer network is a more hostile environment than people realise, with extreme temperatures - both hot and cold - as well as a cocktail of chemicals.

"It's got all sorts of different chemicals down there, from cleaning products which are designed to kill things like bacteria and enzymes in the home, so to use them in the sewer can be quite challenging."

Lipasan uses enzymes to break down the fat, allowing the bacteria to grow and spread

But according to Dr Junker-Buchheit, her company's formula is different from previous treatments.

"This bacteria we are using is very robust, in terms of temperature and different acidity levels," she said.

"This is down to a special culture medium that we have made specifically."

A culture medium is a liquid that forms the bacteria's home while they grow, and can influence the strength and behaviour of the resulting solution.

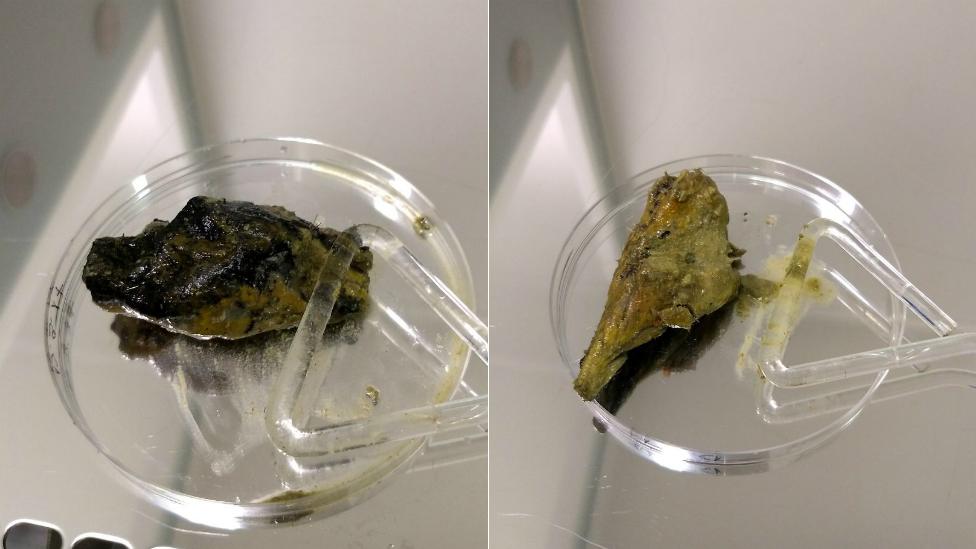

A lump of fat before and after treatment with a few drops of lipasan

The application of the solution, called lipasan, is also very important.

Lipobak uses dosing pumps to inject specific amounts of lipasan into the pipes of the water treatment plant.

The plant pays about €5,000 (£4,500) for a 1,000-litre container of the substance each month, enough to keep the pipes clean and the fatberg problem well under control.

It's certainly not a small amount of money, but the sum pales into insignificance in comparison to the costs of removing a fatberg by conventional means. Depending on the size of the blockage this can cost up to £1m in time and resources, according to Mr Pattenden.

While bacteria may sound like the perfect solution, successfully tackling the fatberg problem in one water treatment plant in Germany is very different from keeping the sewers of an entire city flowing.

Thames Water has 108,000km (67,000 miles) of sewers and clears 75,000 blockages from them every year, at a cost of about £18m.

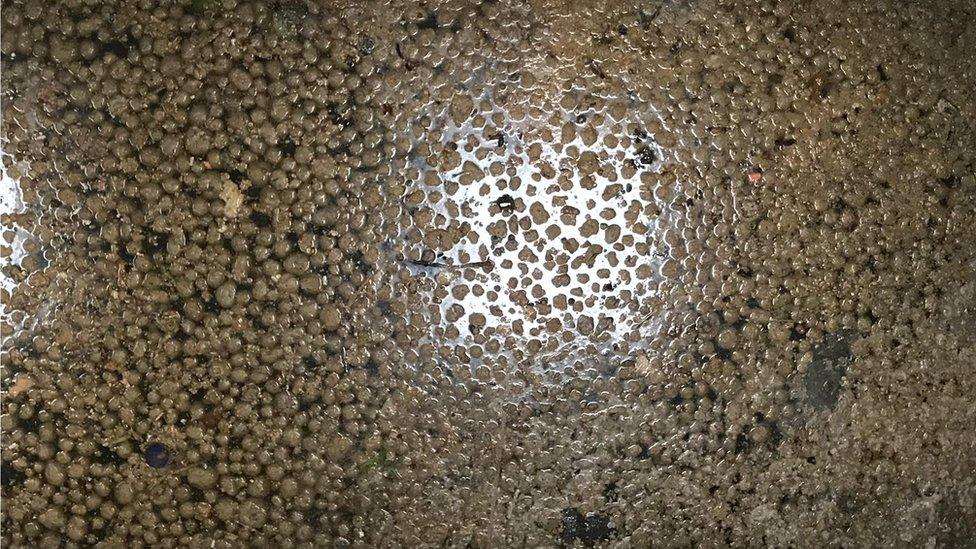

A water treatment tank before and after lipasan bacterial treatment

It simply wouldn't be practical for every household to have a dosing pump and its own supply of fat-eating bacteria but, according to Dr Junker-Buchheit, a strategic approach might work.

"The main places, for example restaurants, they need a dosage system. This would be the easiest way. That would ensure the main systems would be clean."

Mr Pattenden said that although Thames Water was keeping an eye on developments in the world of fat-eating bacteria, he remained to be convinced.

"I think bacteria can play a part in how we treat and prevent fatbergs, but it's not quite a full solution."

The 250m (820ft) fatberg found in Whitechapel in 2017 took nine weeks to clear, and cost more than £1m

There's no denying that fatbergs are a serious drain on Thames Water's resources.

"The really big fatbergs can tie up several teams of people, day and night, for weeks on end," said Mr Pattenden.

"They can cost £1m to take out of the sewer, plus they cause damage to the sewer itself because of how much they weigh."

So what weapons does Thames Water have in the fight against resource-sapping fatbergs?

"We do a lot of stuff with data," said Mr Pattenden.

"We spend a lot of time crunching the numbers and pinpointing activity."

The 210ft fatberg found lurking in Sidmouth's sewers

Once a blockage is flagged up at headquarters, a cleaning team is sent out.

"We send a hose in with a high-pressure jet on it and a great big lorry pumps loads of water in, and it cleans out the sewer."

As well as using sewer-depth monitors attached to the bottom of manhole covers, the company has teams of "sewer flushers" who go into the larger sewers to inspect them.

Thames Water also receives a lot of suggestions from the public about how to deal with fatbergs - especially since the infamous Whitechapel discovery in 2017 - but most "aren't practical".

Mr Pattenden says most proposals involve sending people or robots down to clear sewers manually.

"A lot of customers don't realise what our sewers look like - in reality most are far too small, they're about 20cm (8in) wide."

Of course, the most straightforward solution to the fatberg problem would be to successfully persuade us to change our ways.

Most campaigns by water companies reference the "three Ps" that are fine for flushing - pee, poo and paper - and urge us not to dispose of nappies, condoms and wet wipes this way.

Wet wipes are particularly problematic: so-called "flushable" wipes have been a thorn in the side of water companies adamant that these products are still causing blockages.

A wipe doesn't break down in the same way as toilet paper, meaning it stays intact and clings to fats and grease.

This logo means that wet wipes have been through stringent tests to make sure they degrade quickly

A new initiative from Water UK, external means wipes that have passed its testing will get a "Fine to flush" logo.

Rae Stewart from the organisation said it's all about "ending confusion for customers".

"You've got lots of products out there that claim they're flushable, but the fact is, when they go through the system, they cause blockages and fatbergs.

"The 'Fine to flush' standard is a detailed, rigorous test which wipes have to go through to prove they can break down like toilet paper."

If consumers buy into the idea, it's hoped manufacturers will feel they have no choice but to meet the standard - meaning a key ingredient of the fatberg could be a much rarer visitor to the nation's sewers.

And so although in years to come scientific advances might well prevent fatbergs from building up in the first place, unless we change our ways the answer to this greasy problem will for the moment remain the use of manpower, shovels and a lot of money.

This story was inspired by questions sent in by readers of the BBC News website.

- Published8 January 2019

- Published8 January 2019

- Published21 December 2018

- Published3 November 2017