Rough sleeping: What is being done about homelessness?

- Published

Paul has been sleeping on the streets of Birmingham in sub-zero temperatures

As a night of snow has lashed down on the country and freezing temperatures grip the nation, how are those sleeping on the streets coping?

An estimated 4,677 people a night are sleeping rough on the streets of England. Some have described the ""ruthless conditions" and desperation they face at this time of year.

Paul has been sleeping on the freezing cold streets of Birmingham city centre.

The 49-year-old from Bromsgrove prefers to stay outside all the time than go in and out of shelters.

"I'm used to it now," he says. "When you go inside, you don't feel the benefit of what you've got on, so when you get outside again you just feel colder.

"So if I stay outdoors it's better.

"I've heard it's going to snow. I'll be all right, I'll just stay here."

Almost 600 people died homeless in England and Wales in 2017.

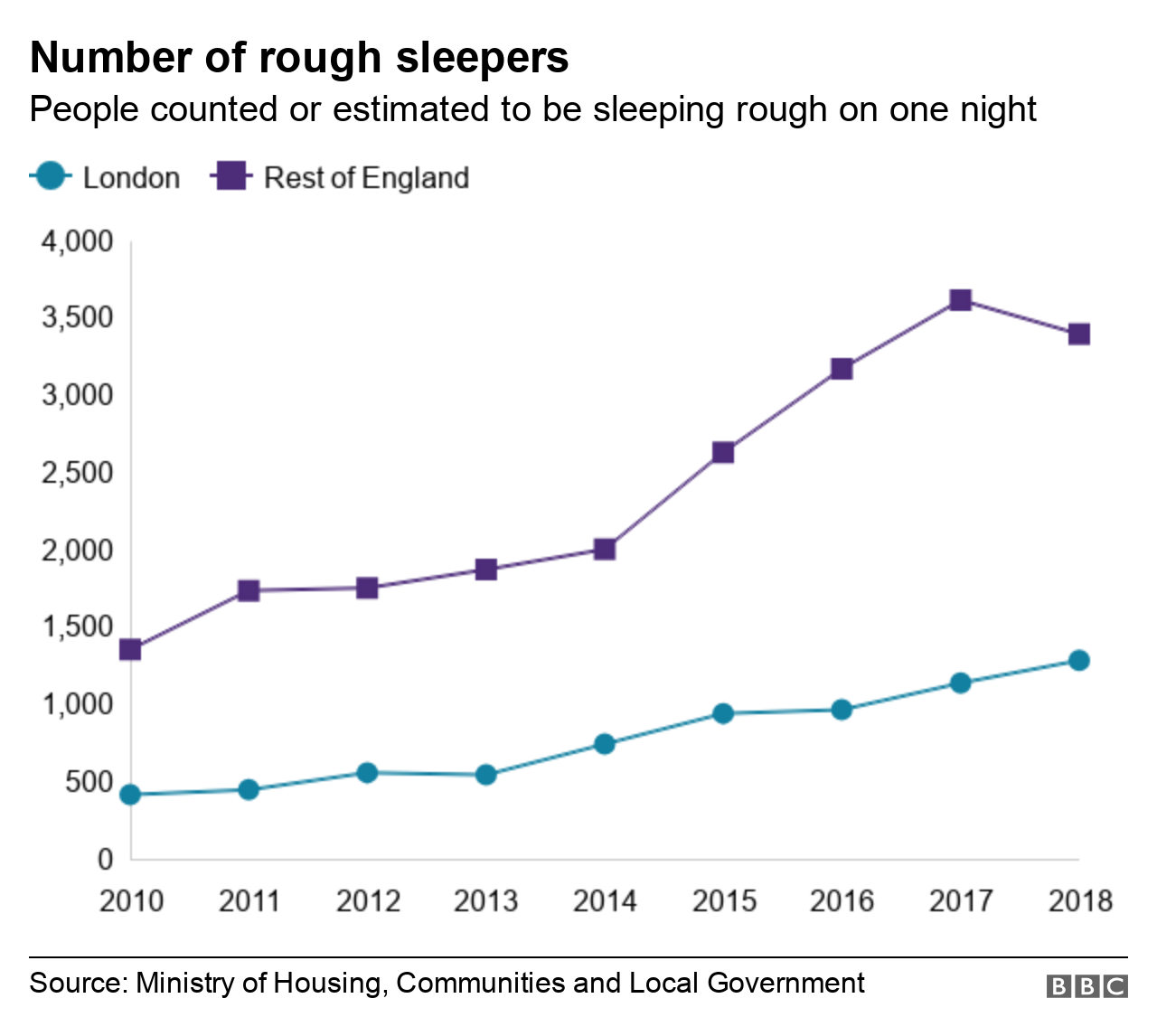

And after seven consecutive increases in the number of rough sleepers, a 2% drop in the past year is no sign the tide has turned.

So what is being done to end a "damning reflection of society?"

What is the government doing?

In 2018 the government announced a £100 million plan to "end rough sleeping by 2027".

About £30m is being spent in areas with high numbers of rough sleepers and councils have used the funding to create an additional 1,750 shelter beds and provide 500 rough sleeping support staff.

However, councils say it does not make up for the loss of funding they used to receive until 2010, the point at which the number of rough sleepers started to climb.

Nottingham Labour councillor Linda Woodings said: "Until 2010 we received a £26m grant for this sort of work, when it was scrapped altogether.

"We didn't have the levels of rough sleeping that we see now when we had properly funded support in place."

Beatrice Orchard, head of policy, campaigns and research at St Mungo's homeless charity said there had been a "sustained pattern of funding cuts" to housing services since 2009.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this map

What are councils doing?

Can the UK learn from Finland's approach to tackling homelessness?

Local authorities have been using the funding to open new shelters where people not only get a bed for the night but also receive help to find housing or treatment for addiction and mental health problems.

Brighton and Hove had one of the highest rates of rough sleeping in England. The council said the number of recorded rough sleepers had dropped by 64% in the past year from 178 to 64.

During the winter months it runs a night shelter at the Brighton centre and a "severe weather shelter" when it "feels like zero degrees" outside.

It also helps fund the independent Churches' Night Shelter during the winter months with support from government grants.

Clare Moonan, lead councillor for rough sleeping, said although the number of people seen sleeping rough had fallen there was "no drop" in the number of people needing a bed for the night.

"Demand is still high. It's an ongoing challenge," she said.

In Bristol the number of rough sleepers counted in 2018 fell to 82, four less than the previous year, based on the one-night snapshot that is used to compile the official figures.

However, the city council keeps a quarterly count as well and says that, averaged out across the year, the number is increasing.

The council opened its first 24-hour shelter, St Anne's, in November. It will stay open until March and then it is planned to re-open again in October, as the nights get colder.

St Anne's in Bristol provides 30 beds and a female-only dormitory

More support staff have also been recruited to help homeless people get accommodation, and officials say they hope this will free up bed spaces for rough sleepers.

The shelter received more than 100 objections when the council proposed it.

In Liverpool, the city council opened a new rough sleeper shelter, external called Labre House.

Mayor of Liverpool Joe Anderson said: "The actual number of people sleeping rough is relatively small, but it is a very visible problem."

Mayor of Liverpool Joe Anderson at Labre House, a shelter for rough sleepers that opened in 2017

People are offered showers, clean clothes and access to computers and phones so they can contact family and friends. They also receive support to find housing and access benefits as well as help to tackle drug or alcohol abuse.

Officials say the project, called the "rough sleeping initiative" has helped re-home more than 40 rough sleepers so far.

What next?

The government will fund 15 centres across England. As well as those in Brighton and Hove, Bristol and Liverpool, the government is funding shelters in Cheshire West and Chester, Derby, Gloucestershire, Lincoln, Medway, Nottingham, Preston and west London in 2019 and another four in 2020.

It promises each centre will help people sleeping rough to be quickly assessed by specialist outreach workers and get support to address the reasons they were homeless in the first place.

It is expected about 6,000 people will have been helped by 2020.

However, Shelter's chief executive Polly Neate has warned that without "fundamental action to tackle the root causes of homelessness" - such as cuts to support services and a lack of social homes - any measures can "only achieve so much".

- Published23 January 2019

- Published13 August 2018

- Published27 January 2019