Surrey earthquakes: Is oil drilling causing tremors?

- Published

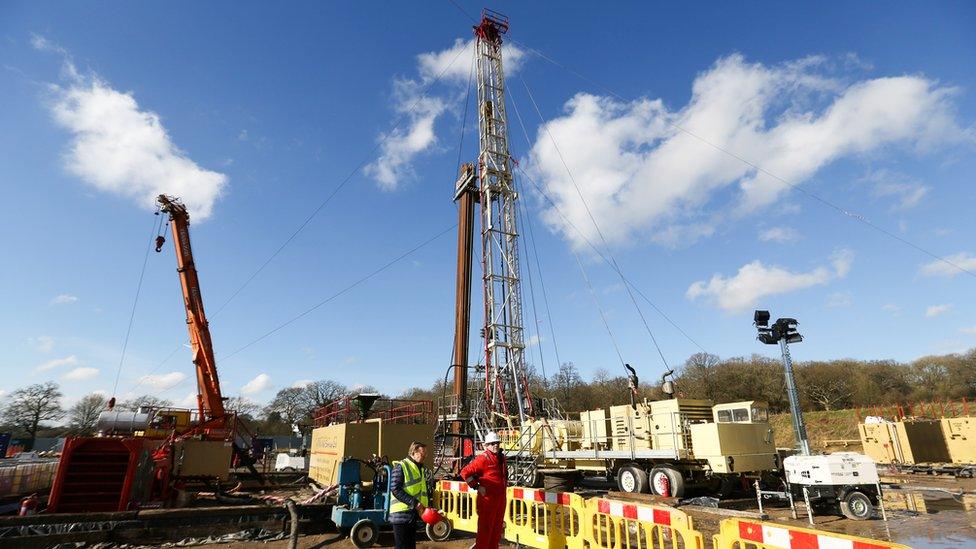

Drilling began at Horse Hill in September 2014

A series of more than 20 earthquakes in Surrey has been blamed on an oil well. A year after the first one, why are scientists still at odds over the cause?

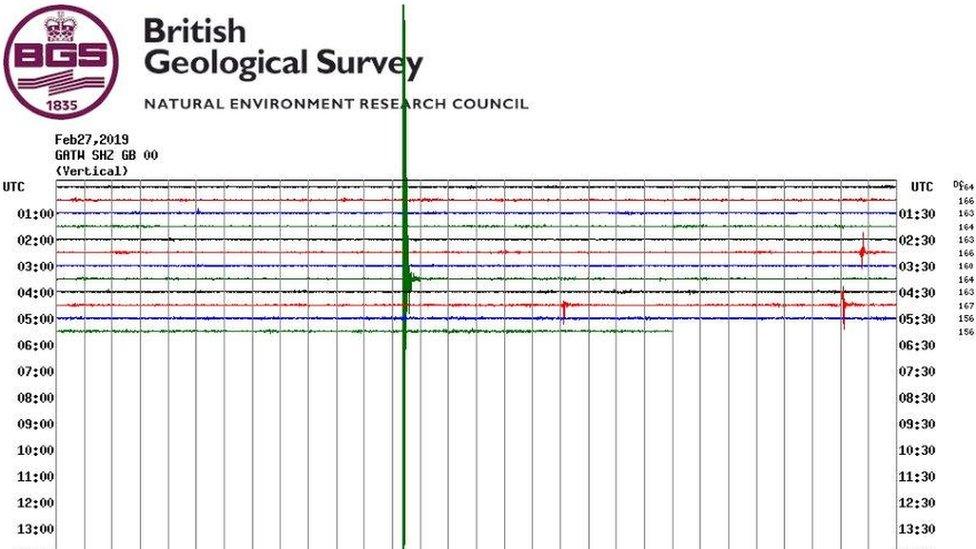

When an earthquake struck Surrey in the early hours of 27 February, worried residents dialled 999.

One caller feared there had been a plane crash and another believed they were being burgled.

"The whole bed was jerking back and forth," said Lynette von Kaufmann, 72.

But unlike those on the phone to the police, she knew exactly why her home was shaking.

It was the strongest in a series of more than 20 earthquakes and its effects were reported up to 10 miles away.

Most had not been felt that far afield, but they have become an increasingly common occurrence for Mrs Von Kaufmann, who lives less than a mile from the source of the tremors in Newdigate.

Climate protesters locked themselves together outside the oil well in October 2014

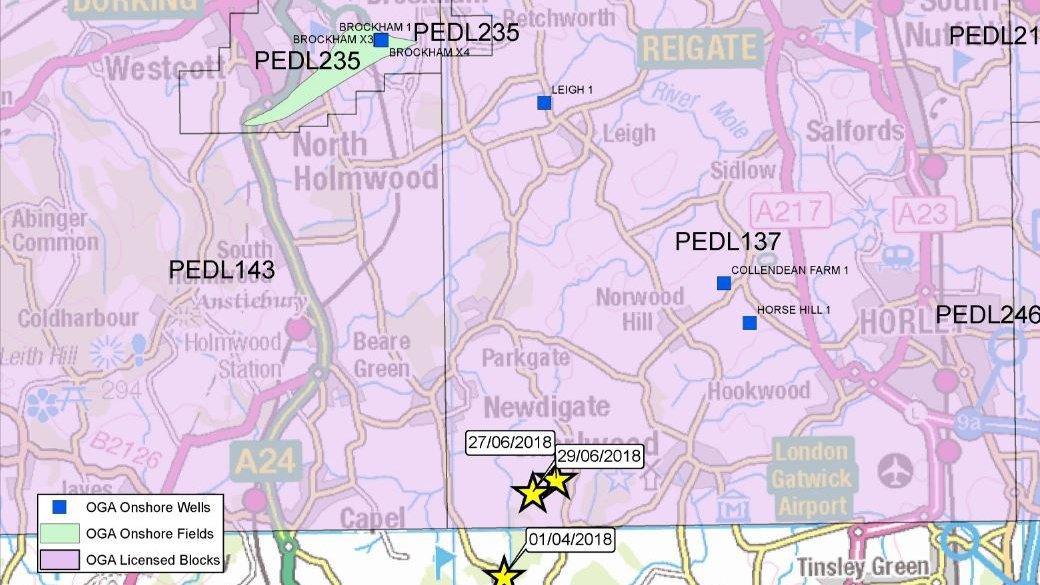

When the so-called "Surrey swarm" began in April 2018, Mrs Von Kaufmann and her neighbours did not have to look far for someone to blame.

An oil well a few miles away in Horse Hill - nicknamed the "Gatwick gusher" due to its proximity to the airport - quickly became the prime suspect.

"There just seem to be too many coincidences," Mrs Von Kaufmann said.

A year after the first tremor, the government has said there is no connection and rejected calls for a fresh inquiry.

Scientific opinion, however, remains divided.

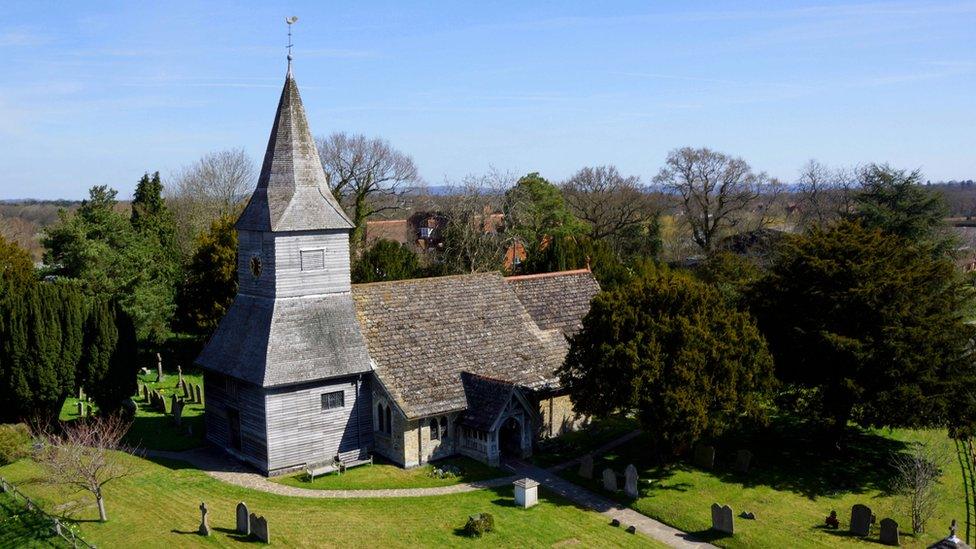

The "Surrey swarm" has centred on Newdigate, home to the 12th Century St Peter's Church

Stuart Haszeldine, a professor at the University of Edinburgh's geology department, believes the oil well is responsible for the "unprecedented" series of quakes.

"Whenever the oil and gas operators start preparing for some intervention, then there is a set of earthquakes," he said. "It's pretty straightforward."

However, Stephen Hicks, a seismologist at Imperial College London, disagrees.

"There's no obvious link to the nearby oil drilling activities," he said.

Emergency call made after Surrey earthquake

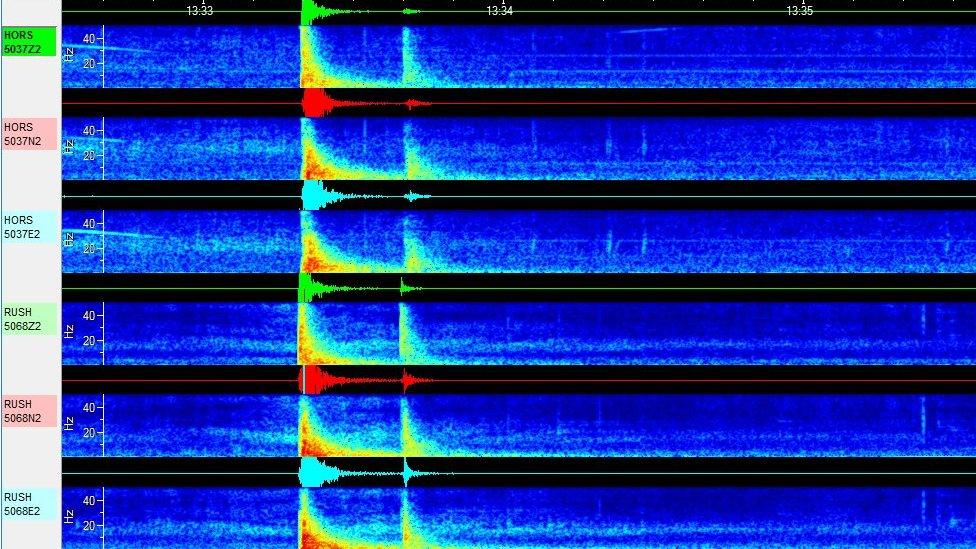

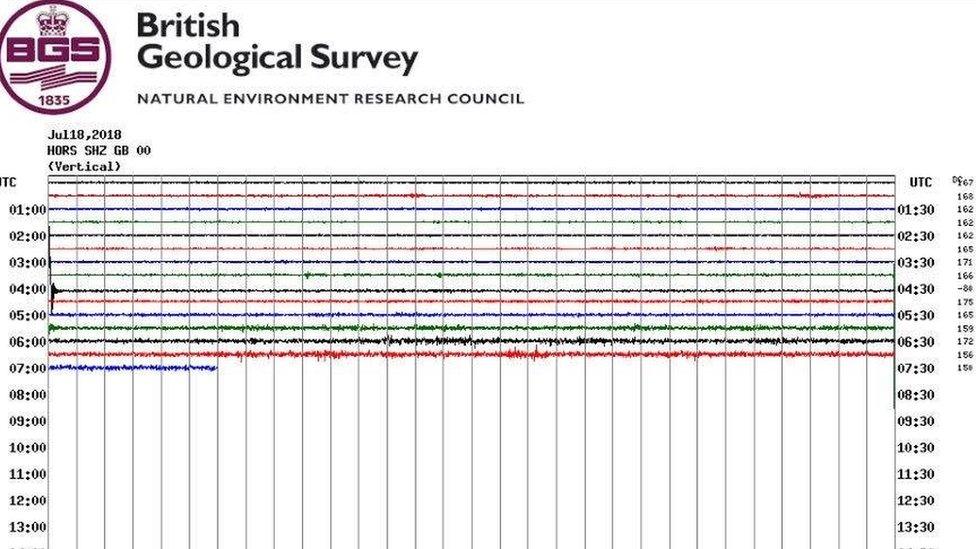

Dr Hicks installed measuring equipment near Horse Hill in July 2018 that allowed the collection of more detailed earthquake data.

He discovered they were clustered 3km away from the well and 1km "below the rock formations that [the operators] are getting oil from".

There was also "no physical mechanism that could explain why these earthquakes would be induced," he added.

The ongoing public debate has exposed entrenched fault lines, with academics, activists, residents and regulators all facing accusations of bias.

Stephen Hicks, left, installed monitoring equipment near Newdigate in July 2018

Even before the tremors began, attempts to draw oil from beneath the Surrey countryside had attracted controversy.

UK Oil and Gas (UKOG) drilled the well, boring into an area known as the Weald Basin, in September 2014. Protesters were camped at the site by October.

In early 2015, the national press descended on the well after the company said early tests had shown they could meet up to 30% of the country's oil demands from a well less than 30 miles south of London.

Speculators flocked to the company, listed on the AIM stock exchange, and some even joined activists outside the site, celebrating the progress of their investment by tweeting videos of oil tankers being driven away.

The protests continued. Some feared the controversial practice of fracking would be used to release the oil. Others objected to the general principle of oil exploration, believing climate change-causing fossil fuels should be left in the ground.

The Horse Hill well - known as the Gatwick Gusher - has featured frequently in the press

When the earthquakes began, opponents of the well found their numbers swelled.

"It's a great campaign," one activist admitted. "Nothing gets people going like an earthquake."

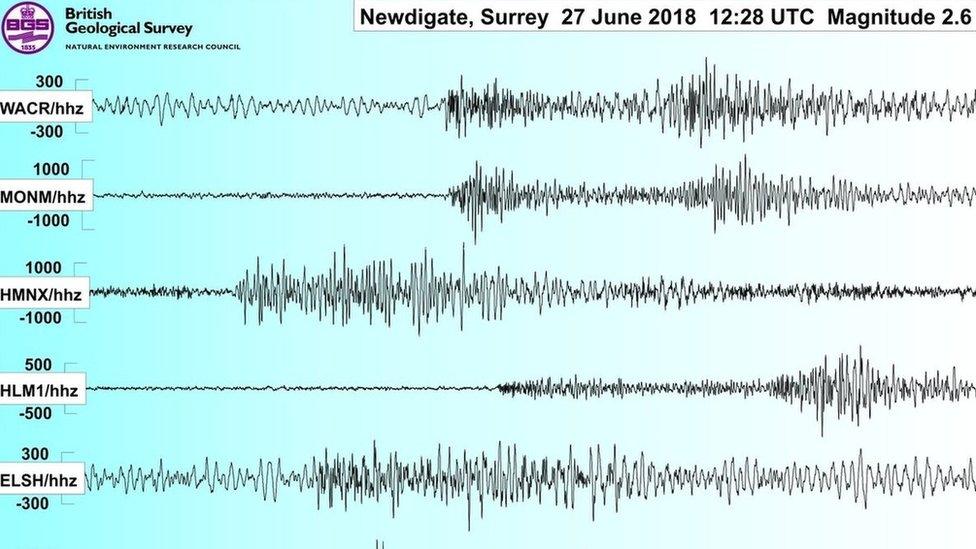

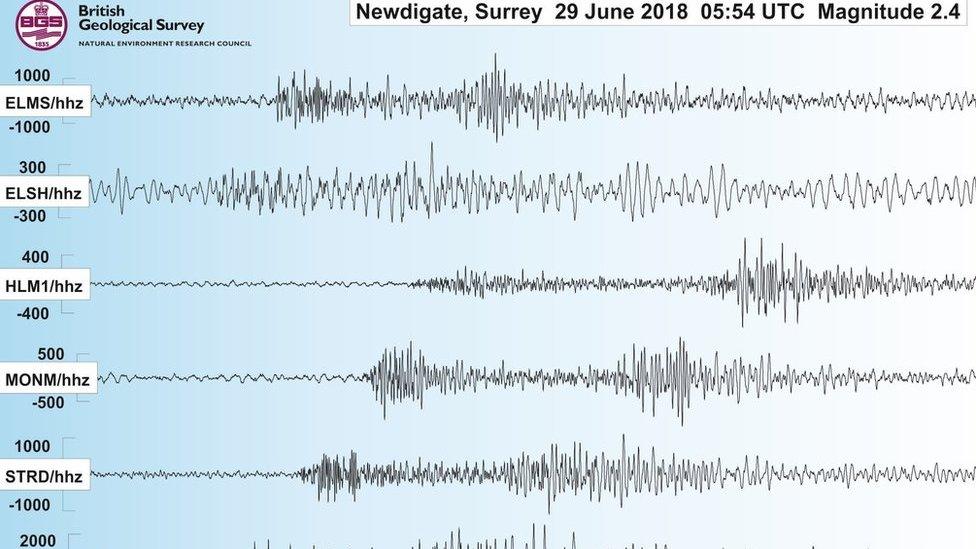

Seismologists from Imperial College London, the University of Bristol and the British Geological Survey (BGS) hope to settle the debate with an academic article, due to be published later this month, that will conclude the earthquakes are natural.

The research, to be published in Seismological Research Letters, found that the relatively small amount of oil being pumped out of the well, during what is known as "flow testing", external, was unlikely to have had an impact "extending more than a few hundred metres".

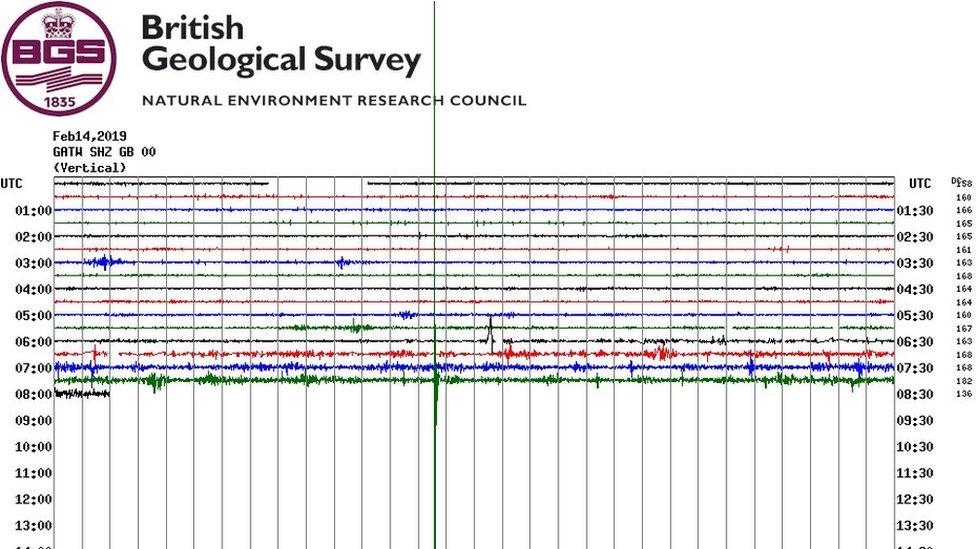

What's more, seismologists found "no correlation" between the timing of the earthquakes and these tests. The earthquakes began in April, but the flow testing did not start until July.

Additionally, they concluded that a 16-year-old oil well in Brockham, more than four miles from the epicentres, was also an unlikely cause.

Their research stemmed from a 20-person meeting in October 2018, which was organised by regulator the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) and led by the BGS after Prof Haszeldine and others first aired concerns and called for a moratorium.

Prof Haszeldine was the only one to walk away from the meeting unconvinced that the earthquakes were natural.

He accepts that he was a lone "dissenting voice", but said it was a case of "groupthink, versus individual thought".

"That doesn't mean I'm right, but all I'm saying is I don't think my questions were answered."

The oil company's financial backers use social media to monitor their investment

Along with two junior colleagues from the University of Edinburgh, he sent an outline of his theory to Surrey County Council in February after UKOG submitted plans to drill four new boreholes.

With only small amounts of oil being extracted at the time of the earthquakes, he looked for a cause that did not involve heavy industrial activity.

"Rather like Sherlock Holmes and the Silver Blaze, it is the absence of evidence in this case which drives us to a hypothesis," Prof Haszeldine said.

He concluded that a build-up of gas might be released periodically to reduce pressure in the well, thus causing the earthquakes.

"That removal of pressurised gas is like letting pressure from a truck tyre - the mass of the truck collapses the tyre," he said.

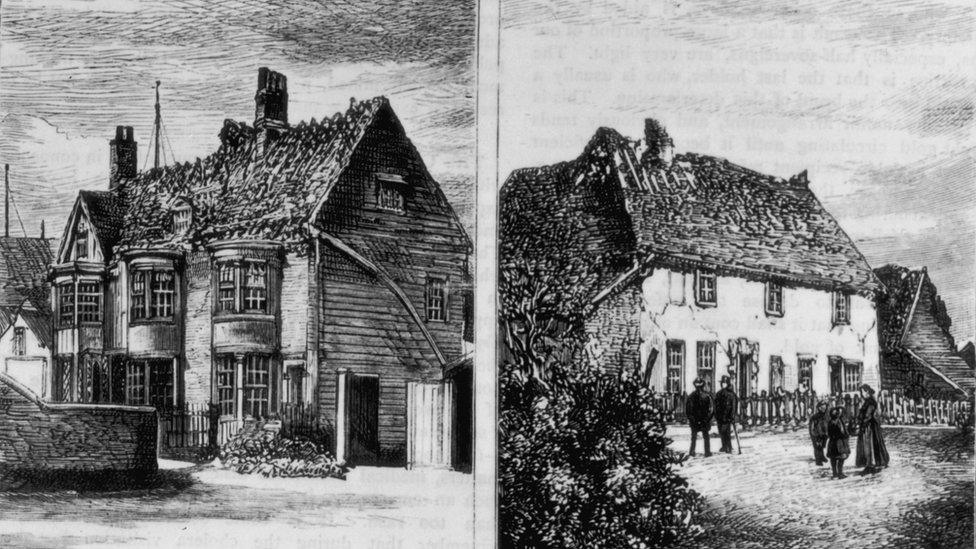

An earthquake in Essex in 1884 damaged about 1,200 properties

Earthquakes in Britain

The vast majority of the 20 to 30 earthquakes that are felt across the UK each year are magnitude 3 or under and do no damage.

None of the Surrey swarm makes it on to the BGS's list of 58 "significant British earthquakes", external, all of which have a magnitude of 4 or more. Less than half of the 30 or so Surrey earthquakes were reportedly felt by people.

The most powerful, on 27 February, was recorded at 3.1 magnitude and seismologists say it was felt by so many people largely because the focus of the earthquake was relatively close to the earth's surface at 2km.

Britain's largest earthquake - a 6.1 magnitude event at Dogger Bank in the North Sea in 1931 - was strong enough to damage properties on the east coast, despite being 60 miles offshore.

More than 1,200 buildings were damaged and three people killed in a 4.6 magnitude quake in Colchester in 1884.

In contrast, there have been 14 earthquakes worldwide with a magnitude of 6.3 or higher in 2019 alone.

UKOG chief executive Stephen Sanderson rejected Prof Haszeldine's theory, pointing to Dr Hicks' research, which shows the earthquakes were "1.1 to 1.4km deeper than anything that we are doing at Horse Hill".

"The mechanism he's suggesting is very arm-wavy. To people who don't understand the way things happen in the subsurface, it has a veneer of credibility, but for people who do, it verges on being ludicrous."

He called Prof Haszeldine a "well-known anti-oil and gas guy", who was "motivated by his own political agenda".

Stuart Haszeldine is a professor of carbon capture and storage

Dr Hicks, who shared seismological data on social media after the earthquakes, said he had faced pressure from both opponents and supporters of the well.

"You are completely stuck in the middle. They will just take a small piece of what you say and use it to fit their agenda, which is irritating."

Fracking - the process of using high-pressure fluid to release natural gases, which has been linked to earthquakes in Lancashire - has been ruled out as the cause in Surrey, with UKOG insistent it only conducts conventional oil extraction.

However, Richard Selley, emeritus professor of earth science and engineering at Imperial College, said it was "very hard to get the message across that the one cause that can be ruled out is hydraulic fracturing".

In a report presented at the OGA workshop in October, he wrote that 2010 anti-fracking film Gasland "casts a long shadow", adding: "Some folk anticipate flames emerging from their water taps."

Protesters feared that fracking would take place at Horse Hill

For her part, Mrs Von Kaufmann said she was "not totally anti-oil," but added: "I just feel the Weald is not the place for it."

In the past year, hairline cracks have appeared in her Victorian home and she fears earthquakes will continue and increase in magnitude.

"That's very scary," she said.

Prof Haszeldine, who describes himself as "wearing two hats" - one of which is as the director of a research group promoting climate-change solutions - accepts that he might be "subject to unconscious bias".

"I absolutely recognise that, but then I consciously try and make sure that I'm not going to get dragged into being a professional objector.

"I am not going to be parading up and down with a placard, saying 'stop all oil production at Horse Hill'."

The Horse Hill well as it looks in April 2019 - Mr Sanderson said it has "less impact than a normal construction site"

He does, however, question the neutrality of the regulator. Established in 2015, the OGA's founding principle is to "maximise the economic recovery from UK oil and gas".

Prof Haszeldine said it was a "big weakness" that left the OGA "conflicted all the time because its job is to produce more oil".

"If there is a judgement call and it's not absolutely compelling that they have to close everything down, then their inclination will be to keep everything going."

The OGA said its focus on "maximising economic recovery" only applied to offshore oil exploration, adding that it also "has a role in evaluating any effects of petrochemical exploration and production along with other regulators".

After hearing of Prof Haszeldine's theory, Reigate MP Crispin Blunt wrote to Environment Secretary Michael Gove last month calling for an independent inquiry to "investigate categorically whether or not there is a causal connection".

Energy minister Claire Perry responded that a connection was "unlikely", citing the opinion of the OGA and the BGS. She said that she did not believe an inquiry was "currently necessary".

Mr Blunt said he was focused on establishing "what level earthquakes would need to reach before one starts worrying about it".

Energy minister Claire Perry said an inquiry was not "currently necessary"

Dr Hicks sympathises with residents looking for answers in the wake of what were "pretty shocking events to those who felt them".

Humans naturally look for "coincidences and correlations" and have long sought meaning in the mysterious movements beneath their feet, he said.

"The Japanese used to think there was some giant catfish under the ocean that was being held down by a demigod and when that god became distracted, the catfish slammed its tail against the earth," he said.

He said the Surrey swarm earthquakes were "probably natural events, just due to natural tectonic stresses".

As to fears they will continue, he said: "The most likely scenario is they will just decay and die off, but then we said that back in the autumn of last year.

"We just don't know."

Follow BBC South East on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, and on Instagram, external

- Published27 February 2019

- Published14 February 2019

- Published20 July 2018

- Published18 July 2018

- Published11 July 2018

- Published29 June 2018

- Published27 June 2018