What's it like to live in a castle?

- Published

Many holidaymakers will have visited castles this summer, but what about owning one, or living or working in one?

Three people reflect on life behind the battlements.

Bamburgh Castle: Looking after an icon

Francis Watson-Armstrong owns a castle, but he hates to say so.

"It sounds nobby to say I own it, I'm more like its current keeper," the 54-year-old says, adding: "I just keep it standing." His castle is Bamburgh, a mighty brick edifice standing above the dunes of a Northumberland beach.

Francis Watson-Armstrong now lives on a nearby farm but grew up in the castle

The oldest parts date to the Norman Conquest of 1066 and it was in a poor state when it was bought by the industrialist William Armstrong in 1894. He rebuilt large parts of it and the castle became the family home.

"It's a massive responsibility looking after one of the most iconic landmarks in the UK but I love it," says Mr Watson-Armstrong, a descendant of the Victorian entrepreneur.

He has fond and mischievous memories of a childhood within its walls."It was awesome," he says, adding: "There were other children my age living there too and we used to terrorise everyone, running around, firing catapults, all sorts of stuff like that."

He was 22 when he took over running the castle with his mother, becoming sole custodian after her death in 1999. He moved to a nearby farm in 2001 but the castle is still a home with 12 lived-in apartments. It is also a tourist attraction receiving 160,000 visitors a year, as well as a wedding venue.

Maintenance is a full-time job for a team of five and, "much like the Forth Bridge", work will never be finished. But Mr Watson-Armstrong is keen to keep the castle in his family. "I'm determined to never let it fall into public body hands," he says.

"It costs hundreds of thousands of pounds a year to maintain and run it, but I would rather meddle in the affairs of the castle myself than have someone who has not lived there, or does not know it, in charge." His son William, 29, is taking on more responsibility for the castle with the hope of increasing visitor numbers and improving the experience.

Francis Watson-Armstrong's family also used to own the Farne Islands and Cragside House

Living in a centuries-old building filled with spiral staircases, narrow corridors and dark corners could be considered to be a tad spooky, but is it?

"I never saw many ghosts apart from when I was in there on my own," Mr Watson-Armstrong laughs. "In a narrow passageway in my mother's apartment I could hear footsteps running; I was certainly sober.

"It's quite eerie on a stormy night and you are there on your own, you just hide under the duvet. If there are any ghosts then I think they are friendly ghosts."

Sizergh Castle: The 'higgledy-piggledy' house

Henry Hornyold-Strickland's family have lived at Sizergh Castle in Cumbria for almost 800 years. Generations of relatives have "chopped and changed" the castle over the centuries, so he feels his family's history is entwined with the "higgledy-piggledy house".

But he doesn't actually own it. In 1950, with the estate's farms facing depressed prices and the family the spectre of inheritance tax, Mr Hornyold-Strickland's grandfather decided to give the castle and its contents to the National Trust. It was handed over on the basis the family would be allowed to keep living there and the deal is still working nearly 70 years later.

"It's not legally binding but is morally," Mr Hornyold-Strickland says. "The National Trust could kick us out at any time but having the original family still living here is a great story for the visitors. It has the potential to be a very tricky relationship - you can see the trust would like everything to be museum-like, but if you are family living here you want to use everything.

"So we do, but we take care of it."

Henry Hornyold-Strickland lives in Sizergh Castle near Kendal

Mr Hornyold-Strickland lived in southern England as a child but would visit his grandparents at Sizergh, before moving in when he was 10.

"It was magical, really," he says. "We spent time exploring and playing and doing the sort of things boys tend to do, whatever my imagination could conjure, like firing our bows and arrows from the top of the tower down to the ground. My grandparents did get annoyed with us for lowering the tone."

One favourite prank was "haunting" guests. Speakers playing spooky noises were hidden behind panels, often eliciting a shriek from the unwitting visitor. "You can see what a hospitable lot we were," Mr Hornyold-Strickland chuckles, before adding hastily: "We don't do that any more."

Sizergh Castle has been in Henry Hornyold-Strickland's family for 800 years

He admits, though, there are parts that do really feel "a bit spooky, especially at night". "You go through a door and the temperature drops 10C and you hear all sorts of noises, which your imagination tells you must be footsteps."

He hopes to stay at Sizergh as long as possible to give his descendants the opportunity to call it home. "I have a strong sense of belonging here, the entire history of my family is in it," Mr Hornyold-Strickland says.

"Sizergh is not an architectural gem but it is a great place to live."

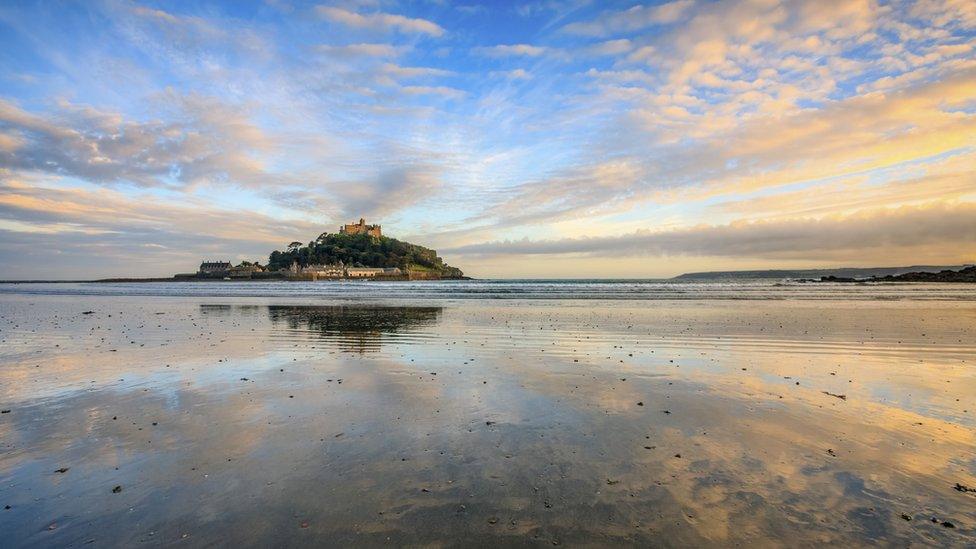

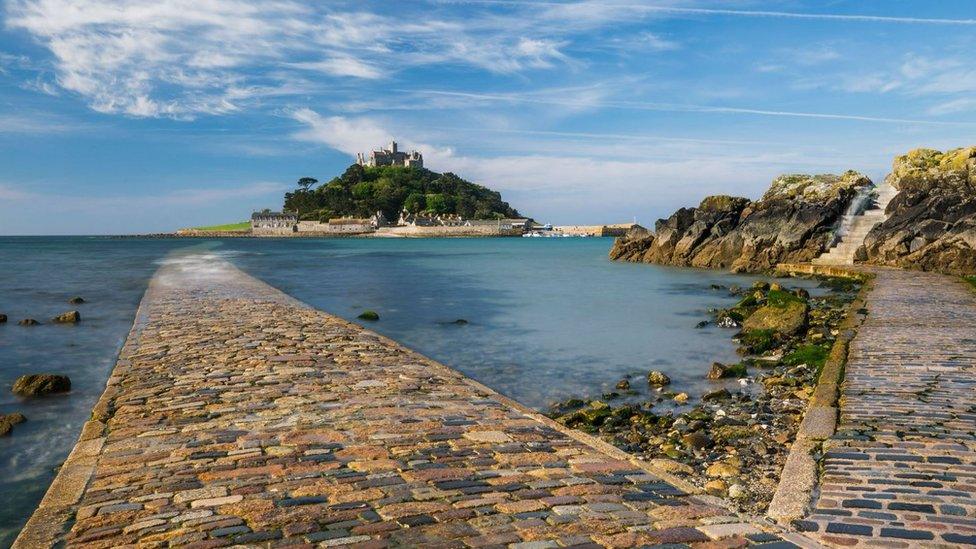

St Michael's Mount: Embrace the lifestyle

Darren Little has lived on St Michael's Mount, a tidal island off the Cornish coast, for most of his life. His father was head of maintenance and his mother a conservation officer, and now he is a gardener.

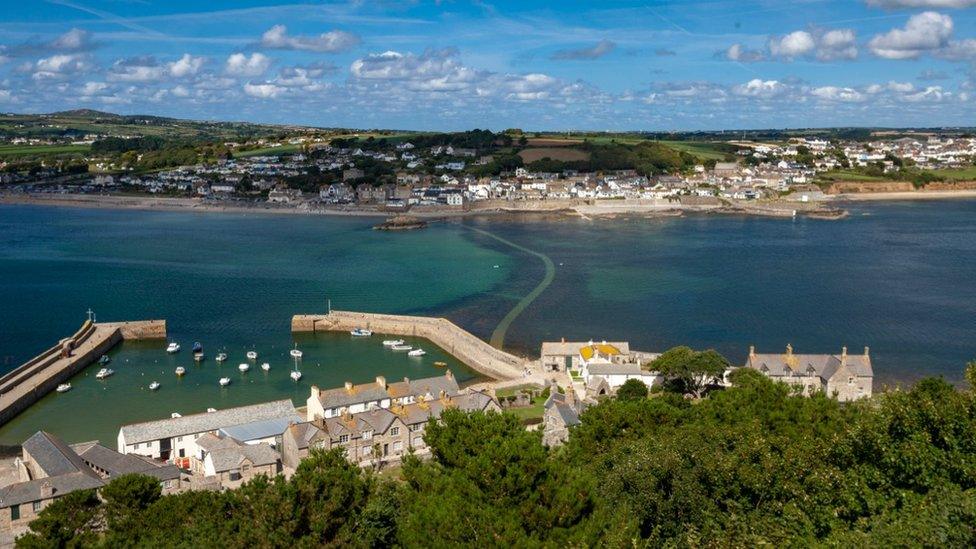

Atop the National Trust-owned hill stands a former monastery turned castle, which is home to Lord and Lady St Levan on a 999-year lease, while Mr Little and the 30 or so other island workers and their families live in two terraces beside the harbour.

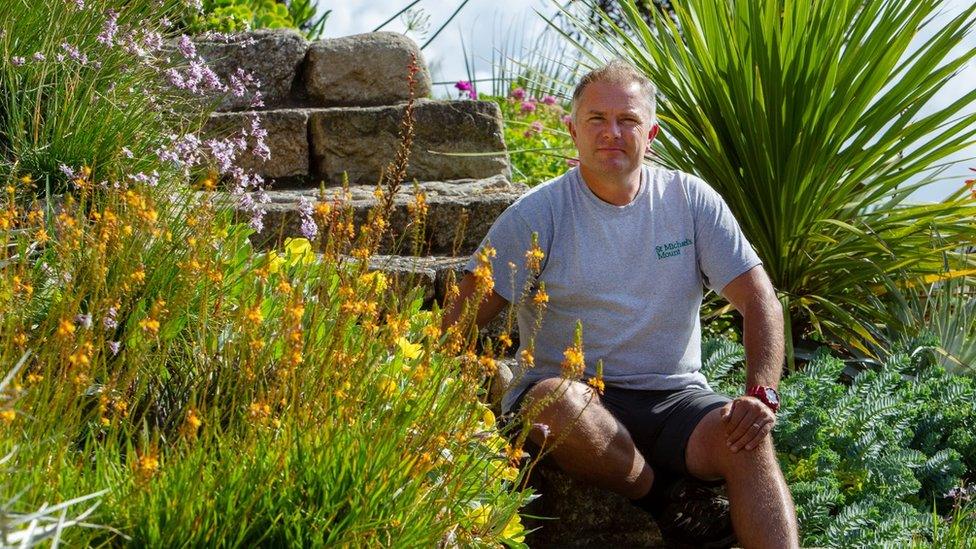

Darren Little grew up on the mount and now works there

Mr Little left at the age of 17, but after 10 years of mainland life he returned to the island's gardening team in 2000. "It was a great place to grow up," he says, adding: "I really loved the place. Coming back was something I was really passionate about. Other kids were amazed with the way we lived on the island. They wanted to come and stay at the weekend."

Much of his childhood was spent in the waters around the island, swimming, canoeing or fishing.

There are two streets of houses and a harbour on the island

Schooling is done on the mainland, with children ferried to schools in Marazion and Penzance each day. If "truly terrible" weather is expected, children are allowed to leave school early or may even stay home for the day, working on computers.

Most also have relatives they can stay with on the mainland should the need arise.

The island is owned by the National Trust

Mr Little has to abseil to reach parts of the garden

"You are always keeping an eye on sea conditions," Mr Little says. A staff bus operates during causeway hours to take islanders to and from the mainland for shopping and such like, and many have cars parked in Marazion.

"There are not really restrictions on how we live," he says. "You cannot put a satellite dish up but there are ways to work around it, like put it in the loft. We get a lot of people looking in the windows but you have to get used to that, it comes with the territory.

"I think they are surprised to see you sat there eating your tea."

A causeway connects the island to the mainland at low tide

After hours, islanders have the place to themselves. "We will often all get together and sit around the harbour drinking tea or having a beer," Mr Little says.

"If you are into partying and socialising it's very restricted here. You have got to use the place for your advantage, make the most of living in such an incredible spot."

- Published31 May 2019

- Published1 May 2019

- Published13 April 2014