The Goldfish Club: The exclusive society of air-sea crash survivors

- Published

By the end of World War Two, the Goldfish Club had more than 9,000 members

"I realised I was going to die - I was very relaxed and completely at peace. I suddenly thought of my wife and children."

In September 1998, Cdr Jason Phillips was stuck in the seat of his Sea King helicopter, trapped under the North Sea off the east coast of England.

Seconds earlier, he and his comrades had bailed out of the aircraft after a fireball engulfed the cockpit.

Jason Phillips is now a member of the Goldfish Club's committee

"I opened my eyes underwater and could see the outline of the cargo door window, which was to be my salvation," says Cdr Phillips, from Helston in Cornwall.

"My seat pack was stuck and, having practised this manoeuvre many times in the pool, I calmly un-snagged it and was free.

"I looked around for my three fellow crew but could only see two. Then came that magic moment when the second pilot swam round the front of our now upturned helicopter and we all realised we'd survived."

Cdr Phillips contacted the Goldfish Club after the crash

Cdr Phillips's training had saved him - and earned him membership of an exclusive club whose sole qualification is that you must have ditched into the sea in, or from, an aircraft.

"I contacted the Goldfish Club membership secretary and explained I had four new members," Cdr Phillips says.

"'Fantastic,' he said. 'We are the cheapest permanent club with an annual membership fee, but have the hardest joining routine.'"

'They were expecting to find a body'

Both engines of Kate Burrows' aircraft failed, causing her to ditch in the Irish Sea

Kate Burrows' flight from Guernsey to the Isle of Man on 16 December 2009 was going well until she reached the Irish Sea.

At this point the right engine in her twin-engine aircraft failed so she turned it off - "I had a spare after all" - and begin a diversion to Blackpool.

Then her left side lost power and Ms Burrows called a mayday. "I chose to ditch - I didn't have a lot of choice," she says.

"I was in the vicinity of the Blackpool gas rigs so I chose to ditch firstly by one of the rigs and then when I saw the gas rig support ship, I chose to ditch 100ft (30m) off its port bow."

"The ditching was so violent I ripped the tail almost off the aircraft"

One of the helicopters from the rigs was tasked to follow Ms Burrows and a helicopter was launched to pick up whatever was left after the ditching - "they were expecting a body", she says.

She describes the noise as "like a cannon being fired behind me", adding: "The ditching was so violent I ripped the tail almost off the aircraft."

Ms Burrows hung on to the straps of her life raft in the water for about five minutes before being lifted on to the support ship and winched into a helicopter.

Ms Burrows was winched into a rescue helicopter

"I did everything I could to mitigate what problems I encountered," she said. "I ditched and came out wet, but alive."

She was soon approached by the Goldfish Club.

"I remembered it from being in the Fleet Air Arm when in the navy," Ms Burrows says. "Some of the aircrew had it on their uniforms but I never thought about it outside the services.

"There's a certain camaraderie about being in the club. We've all suffered the same experience - taking our aircraft swimming - and that binds us."

Eight decades of derring-do

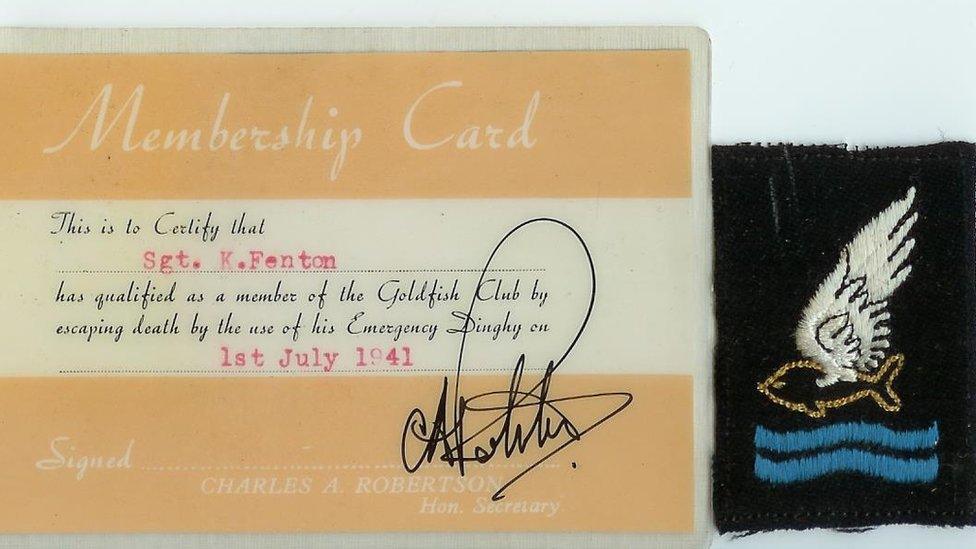

An early version of the Goldfish Club's membership card - granted for "escaping death" - alongside the club's badge

As a civilian pilot, Ms Burrows could not have been a member of the club when it was formed in 1942 by CA Robertson, the chief draughtsman at PB Cow & Co - one of the world's largest manufacturers of air-sea rescue equipment.

Originally restricted to the military, the club had more than 9,000 members by the end of World War Two.

It had been intended further membership should cease at this point, but application forms continued to be submitted.

A dinner is held annually to bring members together - pictured is one from 1953

In 1951, some members inquired about a reunion dinner. The first one was held at the White House Restaurant in London's Mayfair on 26 May that year.

The gathering was such a success it was decided it should become a permanent fixture, and one has been held every year since.

'I started paddling like mad'

Keith Quilter was shot down over Japan during World War Two

One of the club's oldest members is 97-year-old Keith Quilter.

On 28 July 1945, the 23-year-old flight commander was shot down near Osaka on Honshu - the main island of Japan - while carrying out airstrikes during World War Two.

"We'd crossed the coast to a little fishing harbour," Mr Quilter says. "The boss had spotted a small Japanese destroyer and detailed me to take my flight down. We skip-bombed it. I came in low but there must've been some guns down there because somebody hit my engine and it stopped. I ended up ditching in a creek.

"I got my life-jacket and got the dinghy going. I then started paddling like mad for the open sea because we were briefed about the US Navy using their submarines for air-sea rescue. I expected the Japanese to finish me off or capture me. That's why I endeavoured to get out to sea where, with any luck, there would be a rescue submarine.

At 97, Mr Quilter is one of the Goldfish Club's oldest members

"I turned round to see how I was getting on and, lo and behold, there was this sinister-looking submarine coming in on the surface. It got closer and altered course right towards me and I thought: 'Here we go, I've had my chips now.'

"Then I saw the American sailors come down on the foredeck."

Mr Quilter was hauled aboard and it was there he heard the news that Japan had surrendered. "The US Navy was supposed to be a dry navy - no alcohol on board," he says. "I don't know where it came from, but we had a few drinks - I don't remember much of that day."

Mr Quilter joined the Goldfish Club in 2013 after attending a reunion dinner at Dartmouth Royal Naval College as a guest.

"I so enjoyed the atmosphere," he says. "It's a unique group. We're not all RAF, we're not all Fleet Air Arm. We've got all sorts of people. It's quite a family atmosphere."

'The wing is melting'

"It's made me appreciate how things we define in modern society as stressful aren't really stressful at all"

Art Stacey - who is now the Goldfish Club chairman - didn't know it existed until he qualified for membership.

He and six squadron colleagues were conducting a test at RAF Kinloss, near the village of Kinloss on the Moray Firth in the north east of Scotland, on 16 May 1995.

"At that point I'd been in the Royal Air Force 30 years," says Mr Stacey, from Stamford in Lincolnshire.

"We had an electrical short-circuit where wires had been rubbing and a nut on the starting motor which wasn't fit for purpose. It resulted in the catastrophic failure and the destruction of the starter motor, which blew the lower casing off the engine, penetrating the adjacent fuel tank."

A fire spread rapidly through the engine. "The only person who saw the fire was a young sergeant who said 'the wing's melting'," says Mr Stacey. "It's a wonderful description - covers everything."

Mr Stacey says he has been asked "a thousand times" why he decided to ditch into the sea when a runway was minutes away.

Mr Stacey had been in the Royal Air Force for 30 years at the time of the crash

"There was something - years of experience - saying to me, 'you're not going to make it'," he says. "I suspected the aircraft would blow up or I might lose control if the wing collapsed. It was split-second decision-making.

"When we slapped down, the noise was incredible. Every noise you can imagine. It was the loudest thing. My headset, glasses and jockey cap all smashed in slow motion. Then there was silence. Deafening silence."

Mr Stacey was in hospital when he received a Goldfish Club application form.

"I don't think there are many clubs in the world where membership qualifications are so rigid," he says. "I hardly got my feet wet but some guys I've known, unfortunately no longer with us, their survival stories are incredible - in a dinghy in the North Atlantic for a week in winter.

"If you made a film of them, people would say it'd never happen and they wouldn't survive."