Abandoned seafarers: Hungry, penniless and far from home

- Published

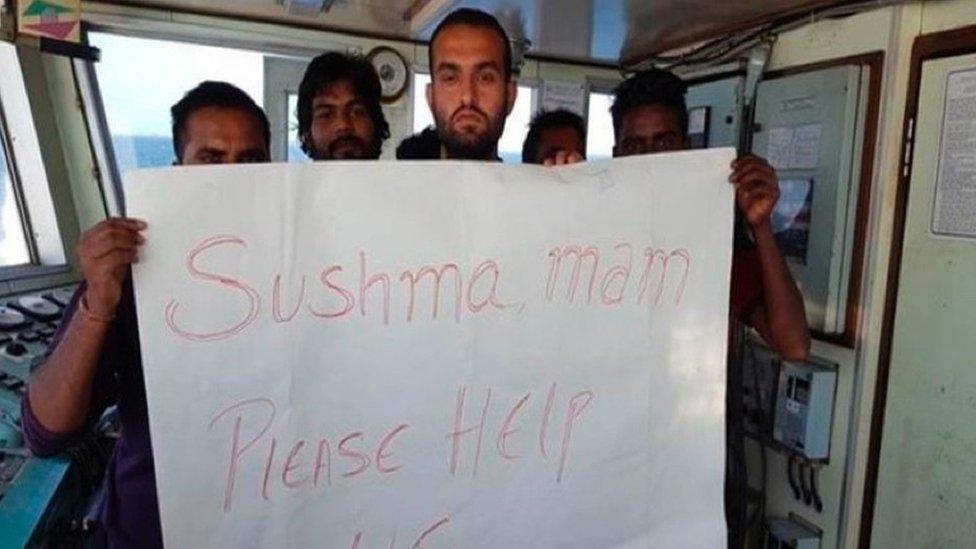

These sailors who were stuck off the coast of Dubai urged India's government to help

When a ship bound for east Africa was detained in Portland off the south coast of England in November, its Russian crew feared they would be stranded indefinitely.

They would have known of the fate that has befallen other seafarers in their situation - hundreds have been stuck on their vessels, some for years, when their ships' owners have run out of money. Sailors who leave their ships in these circumstances risk never being being paid and so feel they have to stay put.

With no income, dwindling supplies and no employer, those stuck in this predicament often rely on the kindness of strangers and the help of charities such as the Southampton-based organisation the Sailors' Society.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In 2017, 40 Indian seafarers aboard a flotilla of merchant ships who had been hired to transport crude oil from the UAE to Iraq were left stranded in waters just off Dubai because of a financial dispute involving the vessels' owner.

The shipping company failed to secure permission for them to enter port and before long life on board became unbearable. Desperate sailors began tweeting about the frightening conditions. They were hungry and in poor physical and mental health - and all the while, bailing out seawater from their leaking vessels.

The situation on board was "tense" with fighting, hunger, isolation and the intense heat all taking their toll.

"Every second on the clock felt like a year," said Rajesh Goli, a captain on one of the vessels. "We used to catch fish from morning to evening," he said of the 11 months he spent stranded within sight of Dubai. "There was no other option for us to survive."

He said it was very hot on board, more than 50 degrees Celsius, but they had no diesel to run the generator for the air conditioner. Sailors took to sleeping on deck because it was too hot inside.

"The ratings sometimes fought each other," Capt Goli said. "They were all very frustrated because they had to do their duty without getting salary or food. It was a very tense situation for me to make them understand."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Initially, the men were able to eat three meals a day but for the final seven months there was only enough food to eat once. They filtered rainwater through a cloth but the unpleasant smell made it difficult to drink.

"Everyone on board was sick - sometimes we only ate once every two days," Capt Goli said. "That affected our health a lot - everyone just dropped weight."

Unable to contact their families and with no clue of when they might be able to go home, many of the crew members suffered mental health problems.

To make matters worse, Capt Goli had taken out a loan to pay the agent who secured him the job. Not only was he unable to send money home to his wife and baby son in Mumbai, the loan interest was spiralling.

After an ordeal lasting almost a year, the sailors were eventually able to return to India, and Capt Goli now works in Mumbai as a chaplain for the Sailors' Society - a charity helping seafarers and their families all over the world.

Its chief operating officer Sandra Welch said ships were typically abandoned when the owners ran out of money to pay the crew or run the ship.

"In many cases, the ship itself is in poor condition, the owner can't - or won't - invest the money needed to repair it and the situation spirals out of control," she said.

"The crew are left powerless and penniless, often thousands of miles from home. Returning home can be practically impossible for seafarers stranded with no fuel, no money and sometimes no permission to access the nearest port."

She said that even if the owner or a charity offered to repatriate them, sailors often choose to stay until their wages are paid as they are afraid that if they leave the ship, they will lose any claims they have on their salaries.

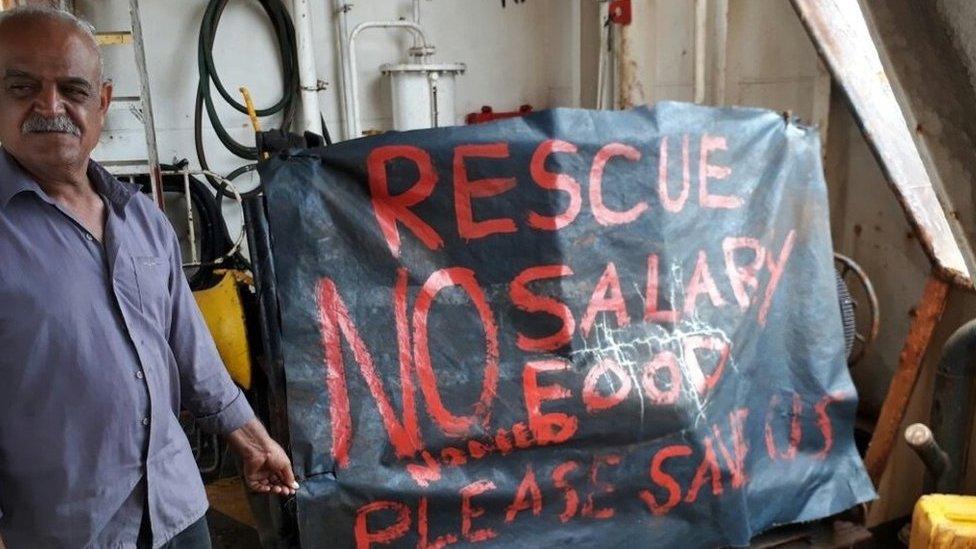

Seyed Nasr Soltan is one of the crew members stranded on board the PSD2

One such vessel is the offshore supply ship PSD2, which has been anchored off the east coast of South Africa since 2015.

Two men, including the captain, have not been paid for nearly five years but remain on board in the hope that one day they will be.

A third crew member was forced to leave the vessel when his wife died of cancer. He was repatriated to Bangladesh with the help of the Sailors' Society, although he it did not make it home in time for the funeral. The charity continues to supply essentials such as food, fishing equipment and medicine to the remaining two crew members.

According to International Labour Organization (ILO) figures, there are more than 160 active cases of vessel abandonment around the world, where crews are waiting to be paid and ships are stranded or detained. The abandoned seafarers database shows there are millions of dollars of wages left unpaid worldwide.

You might also like:

Since January 2017, the ILO's Maritime Labour Convention has required ship owners to have financial protection in place for crews, external in the event of abandonment, death or disability, and any ships entering ports in the 96 states where the convention is in force must provide evidence of their compliance.

The rule, which guarantees four months' wages, was devised because of abandoned sailors' reluctance to leave their ships until they had been paid.

Brandt Wagner, head of the ILO's transport and maritime unit, said that although most providers of financial security - usually insurers - act quickly to meet their obligations, some do not. He said this slowed down the process of repatriation and payment, and sometimes states needed to be encouraged to intervene.

Mr Wagner said there had been an increase in cases of abandonment since the rules came into force, but it was not clear whether this was simply due to more cases being reported than had been the case. In any event, the rules meant fewer seafarers were abandoned for long periods, he added.

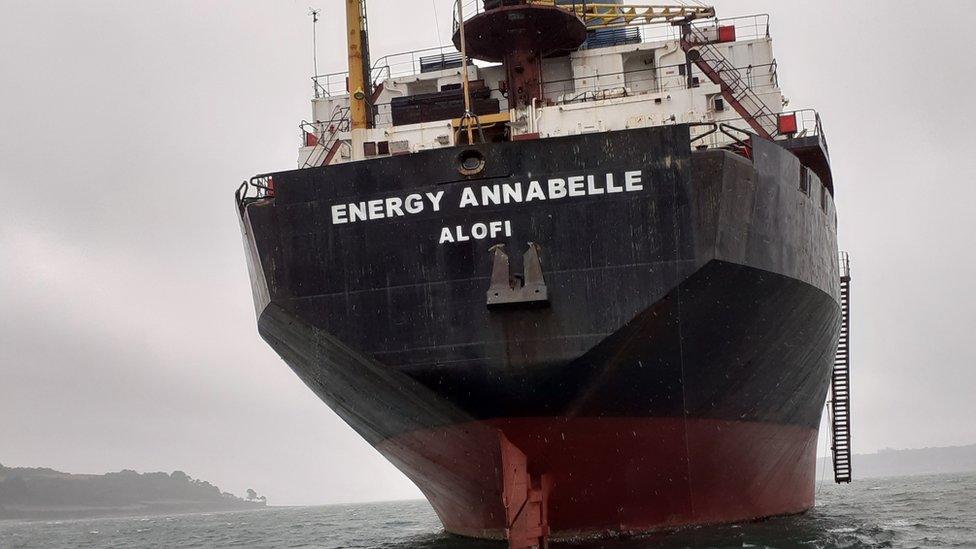

The Malaviya Twenty was stranded in Great Yarmouth for more than two years

According to the Sailors' Society, long-term abandonment is very rare in the UK but, in June 2016, England's east coast port of Great Yarmouth became the unexpected home of the crew of the Indian-registered Malaviya Twenty when it was impounded over unpaid port fees and wages.

Inspections revealed defects resulting in a prohibition notice being placed on the ship. It was eventually forcibly auctioned by the Admiralty Marshal.

While stranded, the 12 crew members were fed by local people and grew vegetables on the ship's deck. A replacement crew from India joined the ship in February 2017 and remained on board until September 2018 when it was bought by a Greek firm and released.

Replacement captain Nikesh Rastogi said: "You learn to adapt, as in you read a lot more... you try to keep up with the news worldwide. Basically, you do that or you slide into depression."

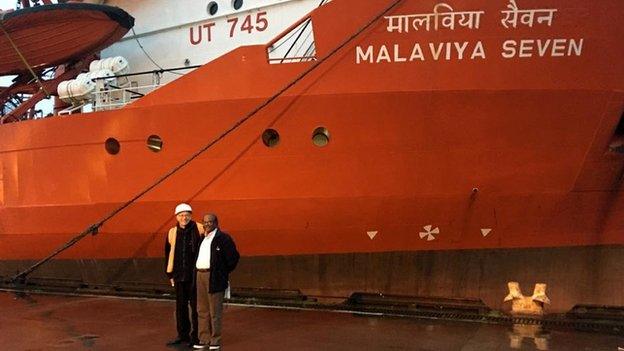

The crew of the Malaviya Seven were stranded in Aberdeen for more than a year

The Malaviya Twenty's sister ship, Malaviya Seven, was also sold in 2017 after being held for more than a year in Aberdeen. The crew of that ship remained on board to ensure they would be paid.

Chief officer Bamadev Swain said at the time: "We have gone through such a difficult time, especially our family members back in India. Finally, God has blessed us. We have endured so much. It was a new experience in life."

For the nine Russian crewmembers who found themselves stranded in Portland in November, their ordeal was much more short-lived.

When their vessel, the MV Jireh, was detained by UK authorities for failing to meet safety and welfare standards, the Sailors' Society stepped in to help, supplying food, a phone and even a birthday cake for the captain.

And, although the ship remains under detention, by Christmas Eve the men had all been paid and were on their way home.

One crewmember, who did not want to be named, said: "Knowing that someone in a foreign land cares about you makes you feel safe."

- Published29 December 2019

- Published18 December 2019

- Published27 November 2019

- Published4 July 2019

- Published23 October 2018

- Published22 November 2017