Shrove Tuesday football: 'No quarter asked nor given'

- Published

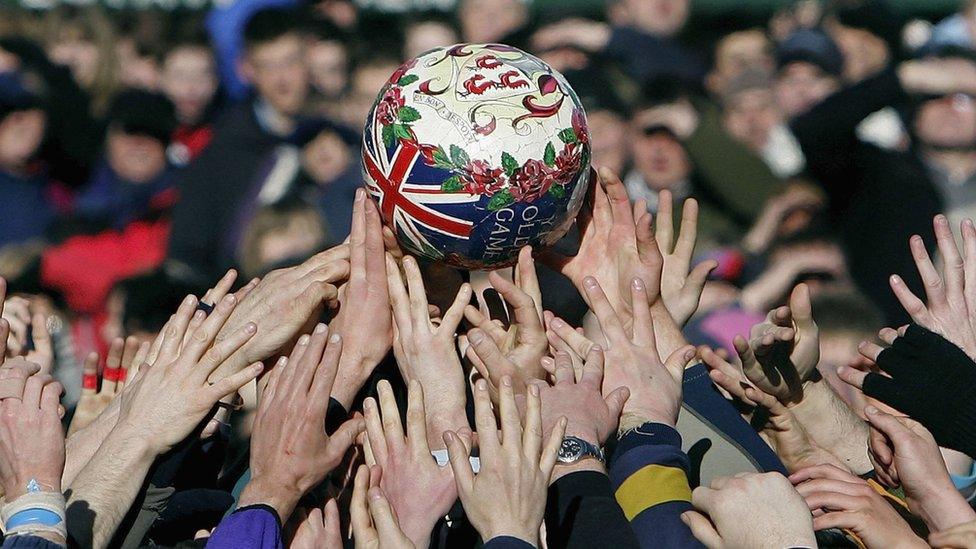

The Ashbourne game is thought to be the largest Shrovetide ball event in England

Shrove Tuesday is not all about pancakes. For centuries, it has also been a day for rumbustious "football" matches with loose rules, limitless participants and - in some cases - outright violence.

Sedgefield is a pretty little town among the rolling fields of County Durham. Its quaint green is edged by a charming church, tearooms and shops.

But for one afternoon each year, the sleepy town becomes a battleground. Dozens of steel-toecap-booted bruisers bash and thrash a small ball through the streets and streams for hours before one person is declared the winner.

"Yeah it does sound a bit mental," laughs reigning champion Michael Adcock, who won the 2019 title after a three-and-a-half hour tussle.

"I try and explain it to people but they don't understand. I love it, it's fun, I never want to miss it."

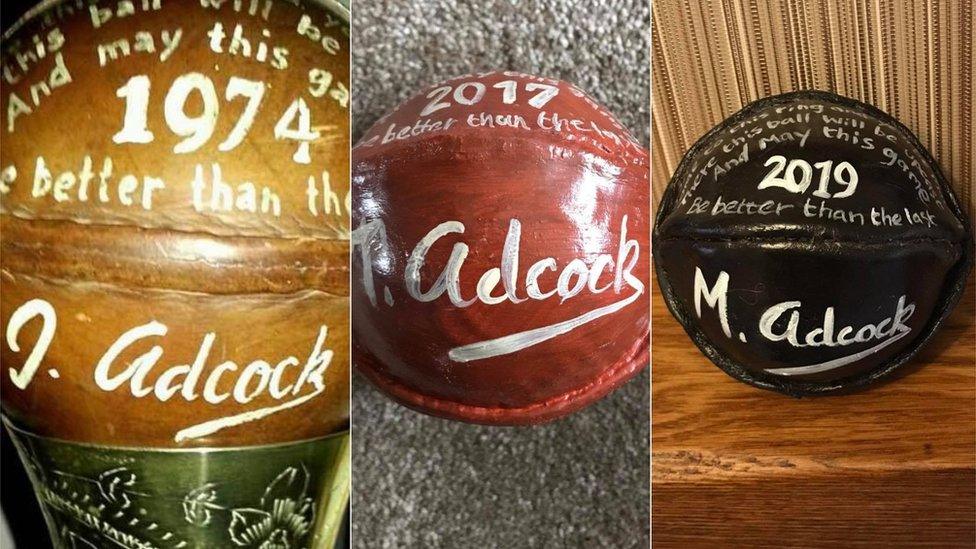

Michael Adcock was declared the 2019 winner of the Sedgefield game after an epic tussle

The 30-year-old is the third member of his family to have victoriously passed the small leather ball three times through the bull ring in the town centre to claim the title.

His father, John, won in 1974 and his brother, Thomas, in 2017, leaving only his other brother, Robert, yet to triumph.

"We do mention that to him," Michael chuckles, before adding with fraternal loyalty: "This year we will try and help him get it though."

The ballgame is a town tradition, and the centre of the scrum is an exhilarating place to be, Michael says; a mass of humanity pushing and pulling at each other, each trying to get a hold of the elusive ball.

Such scrums and scrabbles can be found around England on Shrove Tuesday, from Corfe Castle in Dorset to Alnwick in Northumberland via Ashbourne in Derbyshire and Atherstone in Warwickshire.

Each game has its own traditional quirks and peculiarities known loosely as "the rules". And while some may look rough from the outside, those on the inside wouldn't want to miss out.

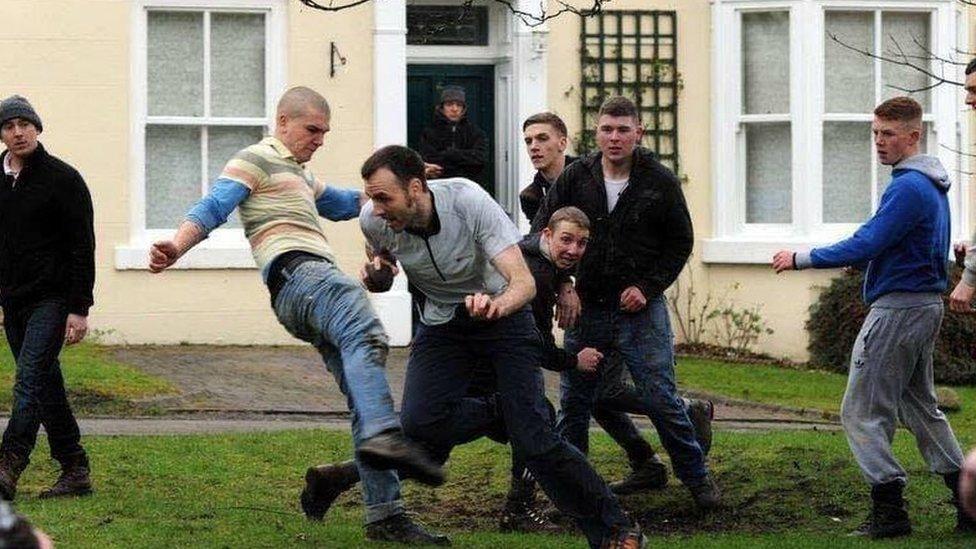

Chris Lines (picture here being "tackled") said it was an achievement to even touch the ball

"It's exactly what it looks like," says long time Sedgefield participant Chris Lines.

"It's frenetic, crazy, absolute mayhem, no quarter asked nor given. But then you will suddenly see everyone stop to let a kid or elderly person have a kick of the ball. There are no rules but there is a sort of code of conduct that everyone understands. If a window gets broken there is a whip-round at the end to pay for it.

Sedgefield Ball Game: Inside the madness of the match

"Taking part in the ball game is a rite of passage in Sedgefield. I would lose a few teeth to be able to say I won it but I'm not big or daft enough.

"I have my war wounds, I still have an area of my mouth that is numb after getting whacked by an elbow a few years ago. I love getting the ball and running with it before being tackled to the ground.

"There is no greater honour in Sedgefield than to win the ball game, and I say that having been the mayor once."

Michael (centre with ball) celebrated his win with his brothers Robert (left) and Thomas, son Freddie, father John and mother Ann

The Sedgefield ball is slightly larger than a cricket ball but just as hard.

To win, the player must dunk it in a beck about half a mile from the centre before returning it to the green for the bull ring finale.

"The beck is pretty scary with like 100 people crushing around you in the water," Michael says, but adds: "You just have to try and stay relaxed.

"My dad told us his stories about the game which makes us want have our own stories to tell.

"You might get a few bruises but no-one is actually trying to hurt each other.

"If something does happen and some have a little fight, you will see them in the pub afterwards having a pint together."

Each winner - including the three victorious members of the Adcock family - gets to keep the ball

Shrove Tuesday football matches have been attested around the country as far back as the 12th Century, according to Dr Ruth Larsen, senior history lecturer at the University of Derby.

The ball was traditionally made from a pig's bladder.

"A game using parts of the animal on a feast day where meat was consumed in large quantities makes sense," Dr Larsen says - particularly given Shrove Tuesday is the last day before Lent, when Christians traditionally abstained from eating meat.

Dr Larsen said the football "season" began on 1 November - All Saints Day - another feast day when animals were traditionally slaughtered.

The Royal Shrovetide Football game in Ashbourne in 2019

While many towns have preserved the tradition, others did away with theirs long ago.

Chester-le-Street in County Durham outlawed its game in 1932. It had been popular - a footbridge over the Cong Burn collapsed under the weight of spectators in 1891 - but the town decided the violence and the damage was too great.

Chester-le-Street's Shrove Tuesday football match was so popular...

...the footbridge over the Cong Burn collapsed in 1891 under the weight of the spectators

"The day before the game the tradesmen of the town would start by boarding up their shop windows - hammering six inch nails into the frames," says Dorothy Hall, chair of the town's heritage group

"Ash Wednesday would then be spent taking them all out again.

"Eventually they got fed up of barricading their stores."

Similar concerns led to the stopping of matches in Manchester and Carlisle during the 16th and 17th Centuries, while Alnwick's match moved from the town's streets to the grounds of its castle in the 19th Century in an effort to make it safer.

Alnwick moved its event to the grounds of the castle in a bid to minimise disruption in the town

Probably the biggest game in the country takes place in Ashbourne where the 16-hour Royal Shrovetide Football match takes place over two days.

The event, which regularly attracts news organisations from around the world eager to cover the alarming antics, gained royal status when a ball was presented to Princess Mary in 1922 on her wedding day.

Shops are boarded up along the main street of Ashbourne ahead of the game

The game takes over the town for two days

Each game follows its own traditions.

In Ashbourne, the whole town becomes the pitch as the Up'Ards - traditionally those born north of Henmore Brook - play against the Down'Ards, from the south.

Alnwick's match uses goals - known as hales - which are 400 yards (365m) apart and decorated with greenery, the game ending when one team has scored twice.

Not all matches are characterised by a sprawling, heaving scrum.

The annual match in Corfe Castle is "just a kick about", according to David Burt, 74, who has been taking part for more than 40 years.

The event here attracts a much more "select bunch" of no more than about 40 people - all with links to the Company of Marblers and Stonecutters of Purbeck.

The Corfe Castle "kick about" is a more sedate affair

The tradition of kicking a ball around the boundary of the town's castle grew out of stonecutters asserting their right to use the ancient path along which quarried stone was transported.

Those games that have survived into modern times show no signs of abating.

"From what I've heard it's actually safer and less violent now than it used to be," says Sedgefield champion Michael.

"My son Freddie is three and comes down to watch and if the ball goes near him he will try and kick it.

"If he wants to take part when he is bigger then I am happy for him to do so."

He pauses thoughtfully before laughing again.

"I'll need to stay fit so I can help him win it."

- Published5 March 2019

- Published14 February 2018

- Published10 February 2016